LSE’s Naomi Pendle says that Chukwumerije Okereke and Patricia Agupusi are successful in presenting a new, in-depth analysis of what it really might mean for development to be homegrown in Africa.

The book, Homegrown Development in Africa: Reality or Illusion? asks whether development strategies in Africa really are autonomous from external control and are, therefore, Homegrown Development (HGD). The book builds these questions from the consensus that Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs) were too intrusive, neo-colonial and incapable of producing lasting economic transformation and that development strategies are now lauded for being homegrown and indigenous, and not just a product of external control. In this context, even IMF and World Bank approaches, such Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSP), have been anchored on claims of national ownership through broad-based participation of civil society. The authors grapple with the question of whether recent national economic strategies in Africa really are “initiated, crafted and implemented by a country without external control” (p.6).

Works that focus on African development carry the danger of seeking a new theoretical panacea to explain  Africa’s inadequate development. The authors do have great faith in the necessity of HGD. From the outset, the book states that “observed patterns of development processes across time and space show that no country has ever managed to achieve sustainable development through externally driven strategies”. The argument is that externally driven strategies result in servitude and a lack of self-sufficiency. Plus, if the goal of development is human wellbeing and not economic growth for its own sake, governments that are free from external conditionalities are assumed to take a longer-term, “human-faced” approach (p.60). Therefore, HGD is assumed as a necessary condition of ‘good’ development, where ‘good’ development is understood in terms of optimum and sustainable wellbeing for the population (p.6).

Africa’s inadequate development. The authors do have great faith in the necessity of HGD. From the outset, the book states that “observed patterns of development processes across time and space show that no country has ever managed to achieve sustainable development through externally driven strategies”. The argument is that externally driven strategies result in servitude and a lack of self-sufficiency. Plus, if the goal of development is human wellbeing and not economic growth for its own sake, governments that are free from external conditionalities are assumed to take a longer-term, “human-faced” approach (p.60). Therefore, HGD is assumed as a necessary condition of ‘good’ development, where ‘good’ development is understood in terms of optimum and sustainable wellbeing for the population (p.6).

Despite the authors’ faith, it is of course very difficult to prove that HGD is really a necessary condition for development in Africa. Has the popular policy discourse really got it right this time? The authors admit that HGD is not the “magic bullet” (p.150), and that policies must not only be homegrown but also effective. Through the book, as they grapple with questions of HGD, it is clear that the authors see the complexity of ideas of HGD in context and have a critical approach to such strategies in practice. The book, therefore, moves the debate along.

The two key questions of the book are: whether development initiatives are homegrown, and whether these initiatives have been effective (p.5). The book draws on material from across Africa but focuses on case studies from Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa and Kenya. This analysis provides the richness of the book.

Each case study includes a historic overview of development strategies post-independence or post-apartheid. These overviews repeatedly portray a post-independence leadership that were strong promoters of HGD. The authors claim that the strategies were truly homegrown in design and implementation, even if results were mixed. The authors do admit that post-independence African leaders did not completely split from external influences. Some historical accounts of this era in Africa would definitely contest these claims of leaderships’ relatively freedom from external influences. There was also often a lack of citizen voice in shaping development policies. Yet, it is useful for the authors to highlight the strength of sentiment in favour of more homegrown policies in this era.

In their conclusion, the authors note that development approaches fall on a continuum from being fully HGD to not being at all autonomous from external control. A big question the authors do not appear to ask is whether, in an age of ever increasing global political, social and economic interconnections for both leadership and citizens, is HGD possible for any country? The authors have great faith that ‘strong and visionary’ leaders can make the difference to the autonomy and effectiveness of national economic strategy (p.160). Is this really still the case in today’s global order? While not discussed in response to such questions, the concept of continuum helps to make the HGD question still relevant even when perfect autonomy might be only imaginary.

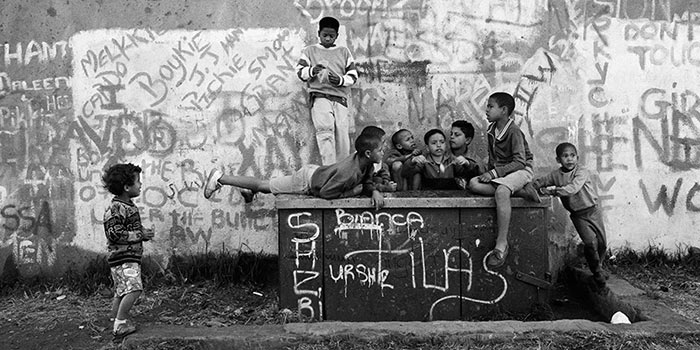

Credit: World Bank Photo Collection via Flickr (http://bit.ly/1ke9QbW) CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The authors conclude that of the four countries considered, only South Africa can claim to have HGD, as their policy autonomy is sufficiently high, institutions are moderately advanced and there is a deep culture of broad-based public participation (p.154). In contrast, Ghana, Kenya and Nigeria are doing little more than implement IMF and World Bank-designed programmes. A dominant reason for this is aid and conditions on loans. The harsher loan conditions that poorer countries face when borrowing money limit their autonomy (p.156). While debt scheduling and cancelling initiatives have been celebrated, in practice they have often only added further conditions. The authors’ conclude that African countries have continued to adopt the neoliberal model without adequate consideration for local imperatives (p.158). While developed countries have economic policies that limit the free-market and that take into account social development, African progress is judged on levels of privatisation.

The authors mention that HGD has a complex relationship with citizen participation (p.155), but is citizen participation a necessary condition for HGD? It would have been interesting to see the authors consider explicitly who in a country needs to control or initiate policies for them to be HGD. Is ownership of strategies just by the elite enough? The book does discuss this theme throughout but it could be more explicitly problematised at the start of the book. This is especially as it is assumed, as discussed above, that HGD will pay more attention to social development. Yet, the experience of history is clear that governments and elites often cannot be relied on to further local interests.

The heart of this book is a detailed discussion of the way development strategies have been initiated, crafted and implemented in Africa in recent years and the extent to which these are still externally controlled. In these case studies a potentially vague debate about HGD becomes usefully grounded. While they share with many the contemporary assumptions of the benefits of development policies that are not externally dictated, they do offer a new, in-depth analysis of what it really might mean for development to be homegrown. Seeing development in Africa through this lens is a useful challenge for policy makers and academics. Yet, the questions and implications of this book are not limited to Africa and easily apply to any country where economic policy has a strong external influence. Therefore, the book should be on the reading lists of anyone involved in shaping development in Africa but also elsewhere.

Okereke, Chukwumerije., and Agupusi, Patricia., (2015) Homegrown Development in Africa: Reality or illusion? London and New York: Routledge. 190 pp.

Naomi Pendle is a doctoral researcher in LSE’s Department of International Development.

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and in no way reflect those of the Africa at LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Thanks Naomi for this detailed and comprehensive preview of Chukwumerije Okereke and Patricia Agupusi’s book on HGD. African scholars have long been trained to emulate, in contrast, no amount of imitation is sufficient enough to stir innovation and long-term mentality for a self-determined path for socioeconomic development. Japan did on their own in Japan, its almost half a century and yet we have not figured out what we want and how to get there. Even forums for Africa’s progress are initiatives that themselves are born in the nations that are architect for the so called structural adjustment programs. Until the day we [Africans] shall be tired of sleeping in the shadows of colonialism, HGDs will just be part of the millions of magic bullets that could have saved the continent decades ago but failed.

Well, thanks for your information today