As Sierra Leone moves beyond the devastating Ebola epidemic, corruption is taking centre stage once again, Jamie Hitchen reports.

“You can tell that Ebola is no longer a constant worry for residents of Freetown,” a friend told me on a recent trip to Sierra Leone’s capital, “just listen to the taxi drivers complain. For a long time they grumbled about the restrictive impact of Ebola, now they are back to complaining about the daily corruption they face”.

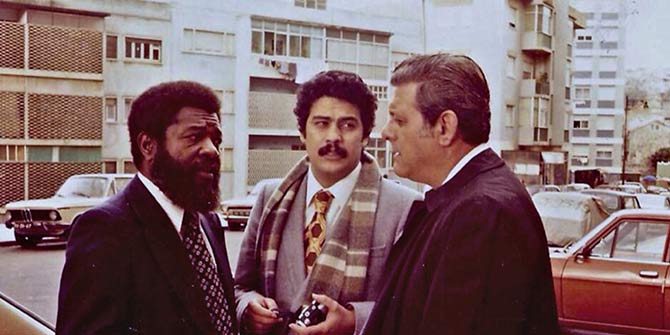

The last man still standing

In the week before 27 April 2016 – the day Sierra Leone celebrated 55 years of independence – musician Emmerson Bockarie launched his latest album. “Survivor” reportedly sold 12,000 copies within 24 hours of being released. Emmerson is not someone to shy away from controversy. His self-proclaimed status as “the last man still standing” is a reference to his continued artistic independence and resistance to political interference.

Back in 2007 Emmerson’s album “Borboh Belleh” (meaning “gluttonous boy”) castigated perceived failings of the Sierra Leone People’s Party government. In an election year, it gathered widespread popular support which the All People’s Congress (APC) used to its advantage. After his election as president, Ernest Bai Koroma specifically recognised Emmerson’s outstanding ability to raise public awareness through music. It is fair to say that the APC response has not been so positive this time, not that Emmerson seems perturbed. He told journalist Umaru Fofana “I have made up my mind to do what I am doing and cannot stop now”.

Striking a chord

One track in particular, “Munku boss pan matches, e jus dae krach”, highlights the rampant corruption that – Emmerson charges – has become part of the culture of the APC government. The title translates as “ill-educated people who keep lighting matches one after the other, just to see the fire again, for no other reason than because they can”. What this alludes to – and this was very clearly understood by the people I spoke with in Freetown – is the recent spate of corruption and the mismanagement of state resources by politicians and government officials only interested in advancing their own interests rather than the development of Sierra Leone. An equivalent metaphor in English might be “like kids in a sweet shop”.

With a playtime of 15 minutes, the lyrics of the song prod and probe at length. They question the commitment shown by all government departments to the construction of roads even when it is not within their remit to do so and despite the glaring needs elsewhere: roads are an infamous source of kickbacks. They condemn the empty promises made regarding jobs for youth. They accuse MPs of failing to represent the voters and of being “under the brown envelope payroll” and question the validity of the “more time” agenda that supports an extension of the incumbent governments mandate, due to expire in 2018, to continue mitigating the disruption inflicted by Ebola. As for the president himself, Koroma is accused of accelerating his accumulation of wealth as he nears the end of his time in office and of indulging in a lavish lifestyle starkly at odds with that of most Sierra Leoneans.

Public reaction

“He [Emmerson] sings for us,” Foday Conteh, a taxi driver from the president’s home town of Makeni, told me. From health workers, to university students and staff, to business owners the response of everyone I spoke to about the song was similar: a wry smile followed by a question as to whether I understood the meaning of the lyrics. There was broad agreement that Emmerson was speaking the truth.

Of course, some disagree. Writing in Cocorioko, editor and a diplomat appointed to the UN by President Koroma, Kabs Kanu asserted that “Emmerson’s lyrics did not reflect the true story about what President Koroma has done for our nation. There have been far more than just road construction in Sierra Leone. Every aspect of national development has been touched by the President”. At various locations in Freetown, Airtel billboards depicting the artist were vandalised.

Emmerson’s accusations would be difficult to prove in a court of law, but they have certainly been embraced by a receptive audience. Amid the blare of horns in Freetown’s gridlocked traffic, the song resonates from the shared taxis on which so many commuters rely.

For most Sierra Leoneans water shortages, increases in the cost of living – the Leone has plummeted against the US$ since August 2014, driving up the cost of many foodstuffs – and a lack of formal sector employment are the everyday realities. Beyond new roads and a few token traffic lights, there is little sign of much-needed investment, for example in health care, education or agriculture. For now, citizens continue to endure the hardships with good humour. But if the wealth divide continues to widen, and poorer residents of Freetown are forced to suffer even more while a fortunate few thrive, there will come a point when something will have to give.

This article was first published on the Africa Research Institute blog.

Jamie Hitchen is Policy Researcher at ARI. He wishes to extend special thanks to Joseph Macarthy for his invaluable assistance in bringing clarity to the song lyrics where he was unable to do so. Follow him on Twitter @jchitchen.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the Africa at LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.