Roland Benedikter and William Mensa Tsedze present a retrospective analysis of the progress and issues faced by Togo since its independence.

Togo, one of the smallest and peripheral nations of West Africa, has undertaken a long march towards democracy since the 1960s. But much progress still has to be made. The European Commission’s New Partnership With Africa After 2020, due to be initiated in 2017, could become an anchor for civil society startups and NGO initiatives. It could foster new cooperation in economic and political development from below (ie parallel to existing political and regime patterns or even outside traditional political trajectories) therefore triggering growth that benefits all and making Togo an example for other geopolitical areas within and outside Africa.

Without a doubt over the past few years, Togo has made economic progress, albeit without political reforms. However, the respective process threatens to lead to nowhere for the majority of Togolese citizens. Like other smaller African nations, Togo may often feel ignored because of its size, but it could grow in influence in the future due to its huge economic potential. To maximise the latter, good governance is essential. Togo has made some headway with regard to development, although the majority its population has failed to benefit so far.

For example, while there has been progress in the fight against HIV/AIDS and for broader access to primary education, the picture of the social situation in Togo remains, to say it bluntly, rather dismal. One out of two Togolese does not have access to drinking water and electricity. There is about one physician for every 14,500 inhabitants, and 55.1 per cent of the population is living in poverty. Public higher education provides training which does not meet the needs of the country’s labour market and development issues. Many students take their notes on the floor; and students must arrive at the university at 4am in order to get a seat in a 7am lecture. High schools and universities accept students up to three or four times their normal capacity. While the rate of primary school enrollment of 83 per cent is relatively satisfactory, the quality of education raises serious problems, with an estimated unofficial literacy rate of 40 per cent. In rural areas, some schools are located under trees, and as a result, classes are normally cancelled during the rainy season.

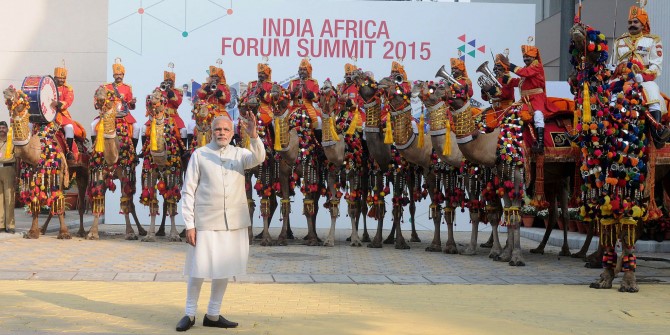

Photo credit: The EITI via Flickr (http://bit.ly/2oyOkF9) CC BY-SA 2.0

Life expectancy remains one of the lowest in the world with an average of 58 years; and the birth rate is more than four children per woman, a clear indicator of underdevelopment, poverty and poor education. Human trafficking remains a main problem, particularly concerning children who are being sold to Nigeria, Benin, Cameroon and other countries. More than 300,000 children from Togo allegedly work in other countries or are labour slaves in their own nation where around 33 per cent of all youth under the age of 14 is believed to be in employment. In addition, there are widespread ethnic tensions between the more than 40 ethnic groups.

In view of the above, the World Happiness Report ranked Togo as the third most unhappy country in the world in 2016, behind Libya and Afghanistan, and ahead of Syria and Burundi. The Human Development Index for 2015 listed the nation 162th out of 166. On April 26, 2012, in a speech to the nation, Faure Gnassingbé admitted that a minority controls the wealth of the country. However, people expect action from their president, not denunciation. In a country with an opposition without a political strategy, whose leaders fight just to be head of the opposition because of the benefits and influence that come with the position, it becomes harder to dislodge those in power. Simultaneously, self-empowerment may help to build better African-European relations, such as the December 5, 2016 decision of five African countries, including Togo, to ban “dirty fuels” from Europe, in particular Switzerland, as part of a transnational environmental offensive. Europe and the international community can and should contribute to support smaller nations such as Togo seeking to achieve stability, participation and progress for their population.

Roland Benedikter (rolandbenedikter@yahoo.de) is Research Professor of Multidisciplinary Political Analysis at the Willy Brandt Centre of Wroclaw-Breslau University, and Research Affiliate of the StanfordGlobal Studies Division (SGS). He is also Global Futures Scholar at the European Academy for Applied Research (Eurac) Bolzano-Bozen.

William Mensa Tsedze (@halbanny) is an environmental and sustainable development activist and member of the World Youth Alliance. Contact: halbanny@gmail.com.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the Africa at LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

4 Comments