As import substitution becomes fashionable again in some African countries, LSE’s Pritish Behuria analyses how successfully this policy can be implemented given the evolving aid and investment landscape.

The international development industry is currently experiencing turbulence and uncertainty. Donald Trump’s victory in the United States elections and the rise of populist politics elsewhere in Europe may contribute to changes in the way Western donors deal with African countries. Trump has proposed a 31 per cent cut that will affect the US bilateral foreign aid accounts and funding for the United Nations, World Bank and other international institutions. Interesting developments in the form of the establishment of The New Development Bank and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank signal new opportunities to access finance. However, these new institutions lack sufficient resources to replace the existing international financial institutions. As the global landscape of aid and investment changes, there may be opportunities for some developing countries. However, for most African countries, these changes have occurred during a period when global commodity price fluctuations have enlarged trade deficits and contributed to foreign exchange shortages. A trend has emerged where countries have begun to use the language of import substitution and economic nationalism more vociferously while the global development regime reinvents itself.

Some suggest that a new era of American isolationism or more specifically – a reduction in foreign aid – may force African countries to adopt more economically nationalist strategies. But such arguments are off the mark. Though import substitution may be enjoying a mild renaissance, in some cases, it is more a result of the downturn in global commodity prices. In other cases, industrial policy returned to government policy discussions before Trump and so did import substitution in some cases (eg Ethiopia). Nevertheless, aid will still be required to cushion the challenges associated with the industrial policies being pursued in African countries. Even with aid, it will be challenging. Without it, it will be near impossible. Ideas such as regional industrialisation or delinking from the global economy or securing the home market are interesting, idealistic options. However, such strategies have rarely been successful attempts at sustaining industrialisation, which have not relied on aid. In East Asian developmental states, international trade (despite adverse terms of trade) was used to the advantage of activist governments.

In the post-World War Two years, manufacturing sector growth was understood to be an essential characteristic of any successful late development experience. With the neoliberal counterrevolution of the 1970s and 1980s, industrial policy was marginalised from development discourse and import substitution was banished from any discussions. Recently, industrial policy has made a return with Justin Lin leading the charge to make such discussions fashionable again. Though industrial policy has returned, some argue that it has tried to stay true to core tenets of neoclassical economics like comparative advantage. Therefore, Ha-Joon Chang and Ben Fine criticise the ‘return’ for barely departing from dominant mainstream discourses and ignoring the history of how countries successfully enacted industrial policies in the past. Nevertheless, such discussions are welcome in many African countries especially since ‘Africa Rising’ narratives have lost their gleam with the sharp downturn in global commodity prices. But these fluctuations have provided a new impulse in many African country governments – the return of import substitution.

Albert Hirschman argued that a significant motive for late developing countries to pursue import substitution in the post-war years was a debilitating trade deficit, which forced foreign exchange shortages because of fluctuations in global commodity prices. Of course, some countries had been more purposeful with their import substitution strategies. Arkebe Oqubay details how such policies were strategically carried out in Ethiopia. The Angolan government has employed such rhetoric for over a decade with varying outcomes. In Nigeria, Aliko Dangote availed the Backward Integration Policy to successfully lead import substitution in the domestic cement sector (and later, export Nigerian cement abroad).

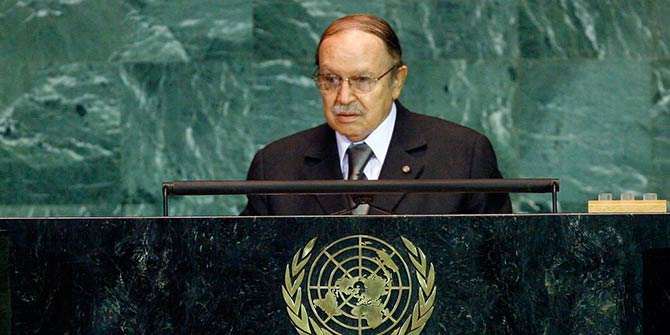

With an eye on worsening trade deficits, several countries have begun reverting to import substitution. The relocation of some Chinese industrial investments to African countries also provides an opportunity to encourage production of locally-produced goods, reduce imports and help domestic firms absorb new technologies. In 2016, the East African Community countries collectively took the decision to ban second-hand clothes again. Tanzania and Rwanda have used such opportunities to develop strategies to recapture domestic markets and promote the production and consumption of locally-produced goods. In Algeria, the government has embarked on an import substitution strategy with restrictions imposed on the import of vehicles, cement and concrete already saving the country six billion dollars in 2016. Volkswagen, Renault and Hyundai factories will soon be established in Algeria to promote local production. In Nigeria, the Goodluck Jonathan government introduced the Nigeria Industrial Revolution Plan in 2012. Since then, Jonathan’s successor, President Muhammadu Buhari has stepped up these discussions and the central bank has restricted access to foreign currency to import 41 categories of items to counter the slide of the naira. Though several companies are in trouble because of difficulties in obtaining raw material, Buhari emphasises the positive benefits associated with encouraging local manufacturing.

The rhetoric of import substitution and industrialisation is alive on the continent. The United Nations has named 20 November as the annual Africa Industrialisation day. The General Assembly declared 2016-2025 as the decade for African Industrialisation. A return to import substitution in many African countries is an interesting development in recent years. When such policies are employed, it will be important to plan more strategically and pay attention to the importance of disciplining learning in national firms while ensuring a transfer of technology and anabsorption of technology in local firms. The successful implementation of such strategies is difficult. It is even more difficult when aid cannot be relied upon to ease the risk associated with shortages of foreign exchange during periods when global commodity prices are volatile. Though industrial policy is back and import substitution is lurking in the shadows, the challenges to enact successful policies will be lessened by the astute use of aid rather than accessing less of it in the short-term.

Dr Pritish Behuria (@PritishBehuria) is an LSE Fellow in International Development at LSE.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the Africa at LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Africa needs currency replacement. Basic tenets of the supply and demand doctrine imply that country X that produces commodity X is meant to be bought by currency X belonging to country X. If country Y wanted commodity X it would first have to change its currency Y to currency X to purchase good X. That is why a euro cannot directly buy any thing from the US until it is changed into a US dollar. But for Africa, Asia and Latin America it’s mineral wealth is not bought by their currencies as the London Metal Exchange only allows the Sterling pound, US dollar, the Japanese Yen, the Chinese Reminbi, the Euro to buy up the entire mineral wealth of Africa. This is not following the underlying axioms to the Adam Smith market doctrine. Then again IMF fixed cross rates don’t reflect what appears in money markets domestically hence distorting the true price of trade. The real value of the US dollar may vary from country to country based on its demand and trade levels. Some countries who trade let’s say with Japan may have a stronger currency in US dollar terms between their currency and the Japanese Yen.