LSE’s Elliott Green examines the life and legacy of Botswana’s second President Quett Ketumile Joni Masire.

Quett Ketumile Joni Masire, President of Botswana from 1980 to 1998, died late on 22 June 2017 at the age of 91. Masire is by no means a household name, even among scholars of Africa, yet he deserves to be remembered as one of the greatest African leaders in post-colonial history, for three reasons.

First and foremost, Masire responded very capably to a seven-year long drought in Botswana that began the year after he took office, which is the country’s longest drought in recorded history and which led to a drop in per capita foodgrain production from 58kg in 1980/81 to only 7 in 1983/84. Botswana’s drought coincided with ones in Ethiopia and Sudan which attracted far more attention since they contributed towards famines that killed hundreds of thousands of people. In contrast, there is no evidence of any deaths in Botswana due to famine under Masire’s watch, largely because of his pro-active Labour Based Relief Projects that focussed on creating jobs on such projects as constructing dams, planting gardens, digging trenches and building fences and houses. His government provided food supplements for children – which was distributed only at schools for school-aged children, thereby encouraging higher school enrolment – as well as for the destitute, disabled and elderly, meaning that some 45 per cent of the population received food relief at the height of the famine in 1984. The drought also coincided with a national election in 1984 where members of Masire’s ruling party ran on their ability to provide food relief and at least some claimed (falsely) that the food relief came from the coffers of the party rather than the state. Indeed, as one opposition candidate said at the time, “how do you convince a man that he should vote for you if he has a bag of food in front of him?”

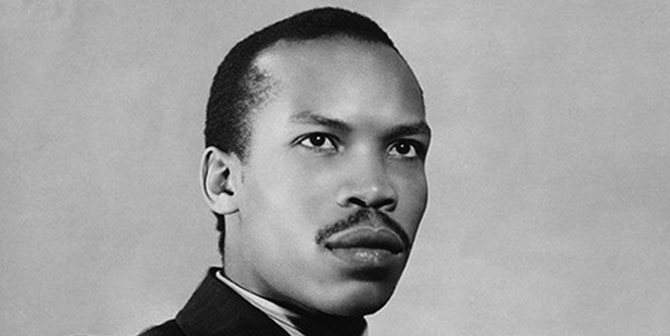

Photo Credit: The LJ Files Blog

Masire’s second accomplishment was to continue the economic success of his predecessor, Seretse Khama. Despite the 1980s being known as the “lost decade” for much of Africa, Botswana continued to see some of the highest levels of economic growth in the world throughout the decade and into the 1990s. This growth was due to the country’s diamond production under the control of the Debswana Diamond Company, which is jointly owned by the government of Botswana and the South African diamond company De Beers. Perhaps Masire’s biggest accomplishment in this regard was the policy of pegging Botswana’s currency, the pula, to a basket of other currencies to make Botswana exports competitive, alongside serious devaluations of the pula in 1982, 1984, 1985, 1990 and 1991. These devaluations made imports more expensive, which is why so many other African countries tended to overvalue their currencies, but Masire was able to resist these pressures and thereby overcome a drop in global diamond prices in 1981 and 1988 that could have been disastrous otherwise.

Masire’s final accomplishment is perhaps his simplest yet most profound: he retired from office at the end of his third elected term in 1998, thereby making him the country’s first President to resign voluntarily from office. (Seretse Khama died of cancer in office in 1980.) The peaceful and democratic transition to Festus Mogae’s presidency set the precedent for future peaceful transitions in Botswana, such as Mogae’s retirement in 2008 and the current President Ian Khama’s presumed retirement next year. For a continent where too many Presidents too often overstay their term in office – including in Botswana’s troubled neighbour, Zimbabwe – Masire’s accomplishment in this regard should not go unnoted.

Of course, like all politicians Masire had his weak areas, most notably as regards his lack of public discussion of Botswana’s terrible HIV/AIDS epidemic. In his defence, however, it is hard to see how Botswana could have avoided the epidemic considering the fact that it is well documented that mining and labour migration – both major parts of the Botswanan economy – are highly conducive to the spread of HIV/AIDS; he also thankfully never emulated South Africa’s Thabo Mbeki by promoting pseudoscientific theories about the disease. Another relative failure was his inability to halt the country’s rising levels of income inequality, which remains among the highest in the world today.

In the end it would be nice if Masire’s death led to a re-examination of his legacy, not just for Botswana but for other developing countries in Africa wishing to emulate Botswana’s success.

Elliott Green is an Associate Professor in Development Studies at LSE.

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and in no way reflect those of the Africa at LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Dr QKJ Masire does indeed deserve to be remembered as a great African. He was a truly humble family man with a warm way and an amazing laugh.

In terms of his achievements it is important to note that he was a ‘master farmer.’ He had a strong attachment to the land and was always concerned to ensure that the agricultural sector had proper support. His economic achievements were many. Ably assisted by his great friend, Professor Steve Lewis of Williams College, Massachusetts, (as well as Carleton College Minnesota and the Ford Foundation) he was able in his original portfolio as Minister of Finance and Development Planning to build partnerships to fund the improvement of the nations educational and skills base. He had responsibility for economic policy throughout so it is a slight misrepresentation to talk of continuation of his predecessors policies in this regard.

It was of course important that Masire retired from office and Botwana’s transitions are instructive. However a single party has governed Botswana since independence and it is perhaps the outcome of the next election in Botswana in which the incumbent party will face an uncharacteristically serious electoral challenge.

The achievement of Masire that is spoken of little but which for Africans is of enormous importance is the assistance he gave to liberation movements. Botswana’s explicit stated policy was that it would not allow itself to be used as a springboard for attacks on the minority ruled states. Nonetheless Zimbabwe Namibia and South Africa’s liberation movements had a true friend in Masire who walked the delicate tightrope between the apartheid regime and the cause of ending minority rule privately giving significant assistance. The speeches at his funeral told some of this story . Masire was a stalwart in the cause of ending minority rule in Southern Africa and Africa will miss him.

Thanks so much for the thoughtful and insightful comment on Dr Masire – both on his accomplishments and shortcomings (especially in relation to the HIV/AIDS pandemic).

I was very fortunate to work in his Ministry of Finance and as part of his national drought relief programme in the late 70s-early 80s. And also to have spent a little personal time with him, under his wing as a young expatriate falling in love with Botswana. He was an extremely warm human being, full of positive energy and surprises. He seemed to wear the burdens of office lightly. Thanks again for the comment.