In Cairo, the rhetoric of sustainability has been a cover for a project of mass displacement, with urban demolition and construction causing locals to be evicted from their homes. Communities have shown resistance by re-claiming abandoned spaces, regenerating them so they can re-encounter old neighbours and childhood friends. These acts, says Chitra Sangtani, complicate ideas of displacement as a linear process.

The de-population of urban centres has long been at the heart of development discourses across the global South. Within Cairo, this agenda has become increasingly tied to a rhetoric of ‘sustainability’ which, in its designs for a more ‘green’ and ‘efficient’ capital, proposes a re-distribution of the population explicitly predicated along lines of class.

Effectively pushing out the urban poor and those residing in so called ‘informal’ or ‘unplanned’ areas to the desert fringes, such plans aim to free up prime real estate land to attract a new class of global citizens, tourists and business elites to the city centre. In this context, ‘sustainability’ has come to represent a particular bio political axis upon which the luxury of clean air and green space is made available to some, while others are selectively dispossessed and erased from the frame of the ‘future’.

During fieldwork I encountered many renderings of a hyper-liberalised world to come: pictures of elite enclaves and high-end residential homes advertised along highway billboards and national television channels. These displays often referred to various timelines or ‘phases’ of construction, each with their own payment plan on offer. Parallel to these visualisations was the production of another set of landscapes: partially evacuated neighbourhoods which, in the aftermath of violent evictions, now lay in a state of ‘waiting’ – between projects of demolition and future construction.

One could not draw a singular narrative about displacement from these visualisations. In some areas, the wreckage of former housing had, over time, turned into garbage sites. With the loss of their objecthood, these materials now straddle the realm of present and historic past, punctuating the built environment with a sense of degeneration and decay. In other areas, these ruins have been turned into productive sites upon which, as Omnia Khalil documents in her ethnography of Ramlet Bulaq, people from the neighbourhood have taken up the labour of cultivation, the rearing of animals and the construction of municipal infrastructures.

Being witness to such scenes spurred my interest in how state-instigated ruin frustrates one’s sense of time, actively undoing the present, while the actions of residents work against this dissolution by pulling abandoned sites back into the lifecycles of the community. In most cases, this ‘working against’ was not so much a choice as a necessary action in the face of economic hardship and destitution.

According to official statements and plans publicised by state bodies, evictees are supposed to receive new apartments in the resettlement towns being built on the outskirts of the city. However, for the vast majority, these apartments are too expensive, too far away from people’s places of work and located in desolate areas where the prospects of finding alternative employment are sparse. Additionally, even for those who want to move, gaining access to these apartments is a process fraught with bureaucratic hurdles and lengthy waiting lists which require people to spend much time and effort in proving their eligibility to housing in the first place. For lack of better options, those who have been displaced commonly end up renting spaces in their former neighbourhoods or re-occupying old homes that, since being evacuated, have undergone significant structural damage at the hands of police or hired vandals.

Such trajectories of movement, return, re-occupation and regeneration, complicate the idea of displacement as a linear process. Rather than de-populate the urban core, the predominate effect of state enforced displacement has been to fold the city back into itself. I found the most compelling example when visiting a small cafe that had been installed on the edge of a vast tract of demolished land in Maspero. It was a very temporary-looking set-up with plastic chairs arranged to face the back of a billboard, under which a flat screen TV was hooked up in preparation for the football match that evening. Located off a busy highway, it was not somewhere one was likely to stumble across.

Yet this football match was well attended. I noted how each person entering the space made their way through several rows of chairs, personally greeting everyone around them before taking their seat. The friend I had come with explained that most people who came here were, like himself, former residents of the neighbourhood that used to exist on the site. With their homes bulldozed to the ground over two years ago, many now reside in faraway settlements such as Al Asmarat or Badr City, but pass by after work or during their daily commute

In the absence of their physical homes, the cafe functioned as a crucial material anchor. It was here that they could re-encounter old neighbours and childhood friends and remain connected to the networks they still considered ‘family’.

While the rhetoric of ‘sustainability’ acts as a cover for a project of mass displacement in Cairo, paradoxically it is the temporary and haphazard arrangements made in the aftermath of urban planning that provided the collective conditions for sustaining life. Such sites cannot be romanticised as emblems of hope or despair, nor can they be managed through the technicalities of planning and population targets.

In leaking different corners of the city into each other in unexpected ways, these places reveal how the future of Cairo is not being pushed by a particular design or masterplan, but rather guided by the routes that people actively make around events of violence and the obstacle of state planning. These are routes that etch themselves into the fabric of the city, creating new relational geographies and modes of being within and despite ruin.

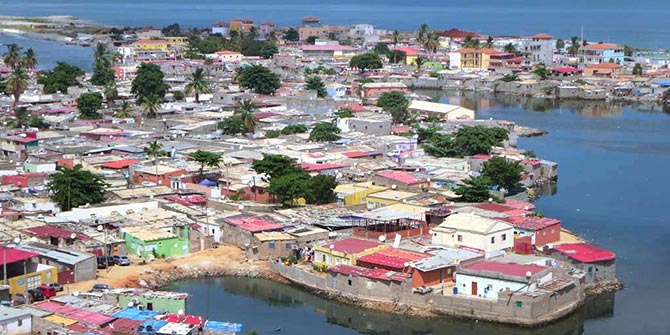

Photo: El-Nozha, Cairo, Egypt by Dan Faltas on Unsplash.