Ethnicity is often depicted as a key cleavage in sub-Saharan Africa. Yet, research on interfaith and interethnic marriages reveals that they are far from rare events and have become more frequent since the 1980s, thus highlighting the need to qualify how ethnic identity is thought about.

A vast literature has debated whether ethnicity matters for economic and political outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa, but little is known about whether ethnicity matters in individuals’ everyday lives. As marriage is arguably one of the biggest welfare-impacting decisions an individual can make, I study interethnic marriage patterns to determine whether ethnicity plays a role on marriage markets.

What do we learn from studying intermarriage shares?

Intermarriages have long been used to measure the strength of cleavages within societies, as they combine a measure of segregation (who meets whom and where) and a measure of who is thought to be an acceptable spouse. My research provides the first quantitative evidence on interethnic and interfaith marriages in the case of sub-Saharan Africa.

I compare patterns of interethnic marriages to patterns of interfaith marriages. Ethnicity is often treated in economics and political science literatures as if it were an unalterable characteristic that is transmitted from parents to children. In contrast, religious identity in African countries is more fluid due to the possibilities of conversion. The interfaith marriage shares we observe are therefore lower bound estimates, as we only consider marriages in which spouses did not convert before marriage. If ethnic (religious) identity matters to individuals, then we would expect low shares of intermarriages along this identity dimension, as marrying within one’s group makes it more likely that ethnic (religious) identity is transmitted to the next generation.

In order to investigate these phenomena, I use Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) spanning 15 countries for which information on respondents’ ethnic identity was collected. I use ethnic classifications that are country-specific, but a religious classification that is common to all countries: Christian, Muslim or African traditional religions and other beliefs.

Marriages across ethnic and religious lines are far from rare events

Interethnic unions are on average more frequent than interfaith unions. Across my sample of 15 counties, 20.4% of women are married to a man who is not from the same ethnic group, while 9.7% of women are married to a man who is not a member of the same religious group. Muslim-Christian marriages are extremely rare, making up only 2.1% of marriages.

However, the share of intermarriages will be driven by the number of categories used and their respective shares of the population. For instance, if there is little religious diversity in a country, there cannot be many interfaith unions. To capture levels of diversity in a country, I therefore compute random shares of intermarriages as comparators, which measure the share of intermarriages we would observe if people were matched at random on the marriage market. Under random matching, across the entire sample we would expect that roughly 80% of marriages would be interethnic and around 34% would be interfaith. When we look at the ratio of the observed share of intermarriages to the random share of intermarriages, interfaith marriages and interethnic marriages are roughly as common: between 25% and 30% of the random share of intermarriages is realised.

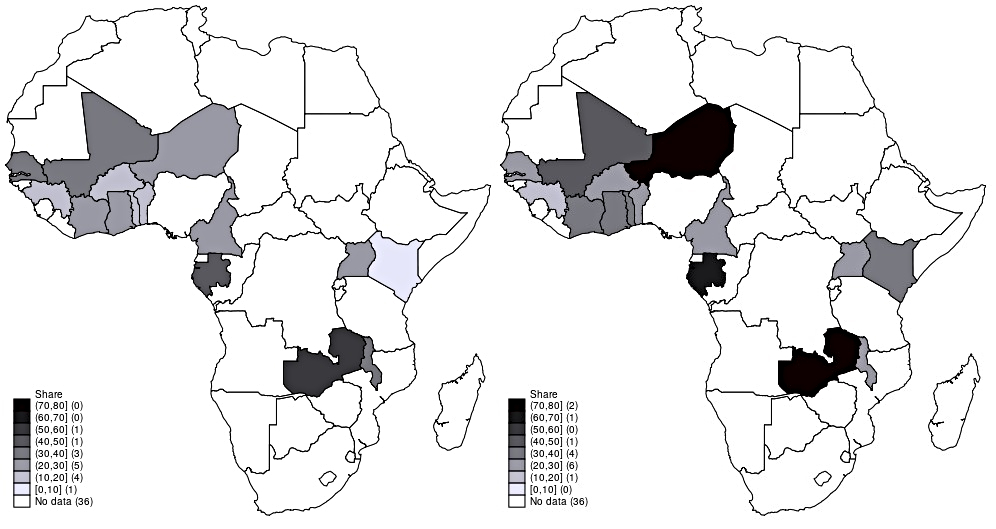

The maps below show the ratio of observed interethnic (interfaith) marriage shares to random interethnic (interfaith) shares. The lowest ratio of interethnic marriages is found in Kenya and the highest in Zambia. The lowest ratios of interfaith marriages are observed in Guinea and the highest in Gambia, Niger and Zambia.

Note: Left panel: Ratio of observed share to random share of interethnic marriages. Higher ratios mean that the share of interethnic marriages is closer to what would be observed under random matching. Right panel: Ratio of observed share to random share of interfaith marriages. Higher ratios mean that the share of interfaith marriages is closer to what would be observed under random matching.

Data: Survey wave (DHS) conducted the closest to 2005. Sample: Women currently in union.

Time trends

Figure 2 shows the shares of each type of intermarriage by birth cohort of women, thus illustrating the rate of change in intermarriage shares. It shows that the share of interethnic marriages has increased over time in the pooled sample. There is no country where interethnic marriages became less frequent. The share of interfaith marriages, in contrast, decreased in the pooled sample. Only in Cameroon did interfaith marriages become more frequent. The share of Muslim-Christian marriages remained stable.

Note: Observed share of intermarriages by birth cohort of women. 95% confidence intervals included. Data: Pooled and reweighted sample of 15 countries: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Togo, Uganda and Zambia. Sample: Women currently in union.

Increasing interethnic marriage shares are likely to be due to the combined effects of increased education levels, urbanisation and changes in norms. Using regression analysis to examine the correlates of being in an interethnic marriage shows an increase in interethnic marriage shares of 4.2 percentage points between the 1960 cohort and the 1985 one, even after education and urban residence are controlled for. Increased mixing and changes in preferences and norms are likely to be driving this effect. In contrast, interfaith marriages have decreased due to the decrease in the share of people identifying with faiths other than Islam and Christianity, mostly due to the decline of traditional African religions. Thus there is no indication of a change in norms around interfaith marriages.

Studying interethnic marriages allows us to qualify the assumptions made on ethnic identity in African countries: most of the economic literature assumes that individuals belong to only one ethnic group, and most surveys conducted in Sub-Saharan African countries do not include an option to declare belonging to a ‘mixed ancestry’ group. In patrilineal groups or societies, individuals tend to identify as belonging to their father’s ethnic group when asked a closed question about their ethnic identity, but will tell more complex stories when asked open questions, and may use their links with another ethnic group (such as knowing how to speak another language) in everyday life.

The high shares of interethnic marriages suggest that it is important to collect ethnic data in ways that allow people to tick multiple identity boxes and for a more nuanced understanding of ethnicity-based identities: boundaries between groups are not always cleavages.

Photo: A wedding in Mukono, Uganda by Andrew Itaga on Unsplash.