Racial, gender and material inequalities are increasingly understood to be deeply entangled and reproduced in the process of doing fieldwork. Our new blog series, ‘Rethinking ethics and identity in fieldwork’, uses an innovative lens based on the experiences of researchers of conflict on Africa to address the limitations and ethics of conducting research, and challenge how the nature of ‘fieldwork’ is understood.

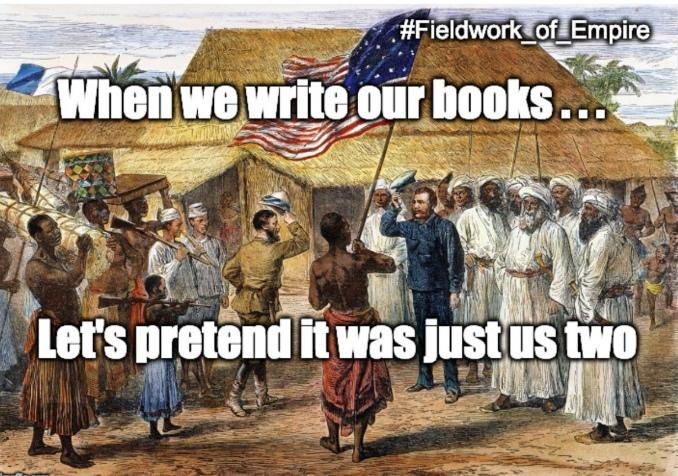

Academics across the social sciences have long turned to studying, unproblematically, African societies as the ultimate Others to the Western world. In recent years, however, scholars have begun to challenge the way that research is actually done and made visible the ‘imperial debris’ that continues to litter the structure and processes of academic research. Against this background, the practicalities, ethics and sensitivities of conducting fieldwork in postcolonial, violent or conflict environments have received increased attention in both academic publications and online platforms.

This blog series joins the growing range of voices that considers the variegated ways through which racial, gender, discursive, and material inequalities are deeply entangled and reproduced within the daily, routinised – and mainly undocumented and unseen – practices of doing ‘fieldwork’. The posts extend from a workshop held in Geneva, Switzerland in June 2019, which drew together a range of scholars working across disciplines and parts of the world to rethink current debates on how we research (societal) conflict. Specifically, it builds from one of the workshop’s panels which made use of visual material as entry points to reflect on the multiple challenges to/in doing fieldwork.

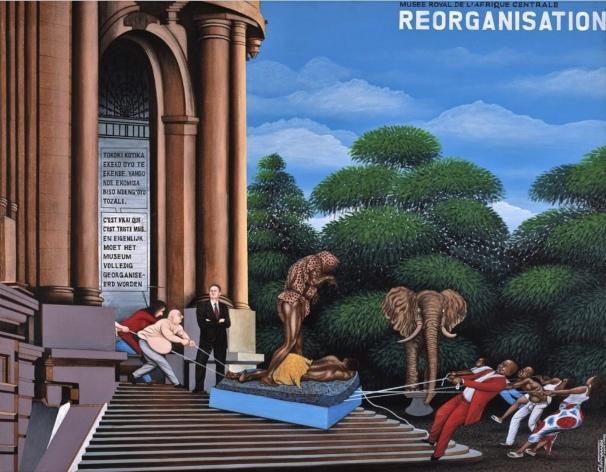

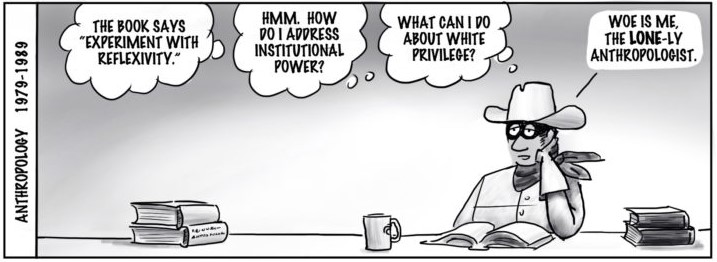

The four contributions thus presented here offer a sample of this panel’s discussions, highlighting the experiences of research in/on the African continent. In particular, each of the four posts offer a different lens for interrogating how we both approach and define ‘the field’. Together, the posts argue for a radical revisioning of fieldwork that approaches the process of fieldwork and the production of knowledge as relational matters while making visible how our sites of fieldwork are morally as well as practically limited. As shown in the photos below, there is a deeply troubling yet still little changed reality of an unequal system that continues to underlie how data is collected, how knowledge is produced, and who gains recognition.

Ryan’s post stresses the need to move beyond textbook methodological procedures, as researchers’ carefully constructed concepts and methods may simply not work in ‘the field’. Speaking from the position of a global North researcher conducting fieldwork in Sierra Leone, she proposes to learn to ‘fail forward’ as a pragmatic way to grapple with and potentially redress the limitations and mistakes of global North scholars collecting data, especially in places marked by coloniality and recent conflict. Although learning from mistakes, she writes, might not resolve structural racial or gendered inequities, this can still go a long way in putting the issue of ‘relating’ – to ourselves and others – back at the centre of research.

Marchais’s post addresses the issues of coloniality and the racialised dimensions of doing fieldwork. Notably, he argues that white scholars are located in and are products of global North institutions and, as such, are inherently bound up in notions of privilege and power. Failing to confront these conditions then recreates the broader conditions for material and discursive violence. Marchais tackles the limits of individual awareness and self-reflexive research practice as blanket antidotes for challenging and addressing racial inequalities within research. Focusing on the individual researcher, rather than confronting the broader structural inequities ingrained within and produced by the wider academic funding environment, contributes to what he terms, ‘the illusion of “post-racial enclaves”’. Race and whiteness thus continue to permeate the structures of research projects and fieldwork practice.

A few weeks before the Rwandan backed militia M23 invaded Goma, the capital of North Kivu, my Congolese friend remarked: 'You are here now but when the security situation becomes untenable, you can leave for a safer haven. You have that option. But we will have to face it. There is nowhere else we can go.' It is exactly this “absence of shared vulnerability” (Niehuus, 2014) that underlies most fieldwork." - Excerpt from Fieldnotes, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Linking concerns of both (personal) moral failure and white privilege, Bressmer’s post highlights her own struggle as a young scholar to adequately navigate the multiple and arguably countless sites where western privilege emerges. Recognising how fieldwork practices shape processes of gathering information in ways that can undermine and invisibilise the agentic power of many with whom we work, her contribution presents a challenge to her readers. She poignantly and critically asks whether it is possible to locate and challenge positions of power in ‘the field’ from within the very same hegemonic space that (re)produces an unequal global society.

Mohamed’s post seeks to upend current understandings of ‘the field’ as a delineated space of formal and intentional extraction and learning. She demonstrates how such conceptualisations often fail to consider the intimate spaces of everyday life – that the sites, relations and encounters we and others experience in the ‘field’ often serve only as a backdrop for our research. She counters that these same overlooked and disregarded spaces, the personal sphere and everyday habits, are the work. In doing so, her piece makes visible the challenge she, as a Somali researcher, faces in Mogadishu, and draws attention to how non-white scholars are also confronted with challenges of positionality, race, and identity in fieldwork.

As the collection of blogs presented here relate, doing research involves friendship, love and kinship as much as it involves power, positionality and privilege – concepts that remain underserved in discussions on ethics, research subjects and scientific methods, even though they rest at the heart of the research process. As such, we need to expand our understanding of the ‘field’, as a multidimensional, relational space that connects geography, history, affect and ordinary politics, especially as individuals from various places experience the world, and power relations, differently.

Photo by Canva Studio from Pexels.