Electricity outages are common in many African countries, but we know little about who bears the brunt of these failures. Research in Accra, Ghana shows that power cuts fall more frequently on poorer people, despite them being less able to deal with the consequences. Research suggests these findings generalise across the continent.

In many countries in Africa electricity demand exceeds supply or transmission capacity. One result of this imbalance is that brownouts or rolling blackouts are common. Over the past decade Ghana experienced long periods of rolling blackouts, known locally as dumsor, the Twi word for ‘off/on’.

During this period the state-owned Electricity Company of Ghana (ECG) decided to ration electricity. The rationing allowed some places to experience a stable power supply, with the downside being that other places had no electricity at all. Having no electricity is obviously unpopular, so the ECG published a schedule pledging that blackouts would roll equally across neighbourhoods in Ghana’s capital of Accra.

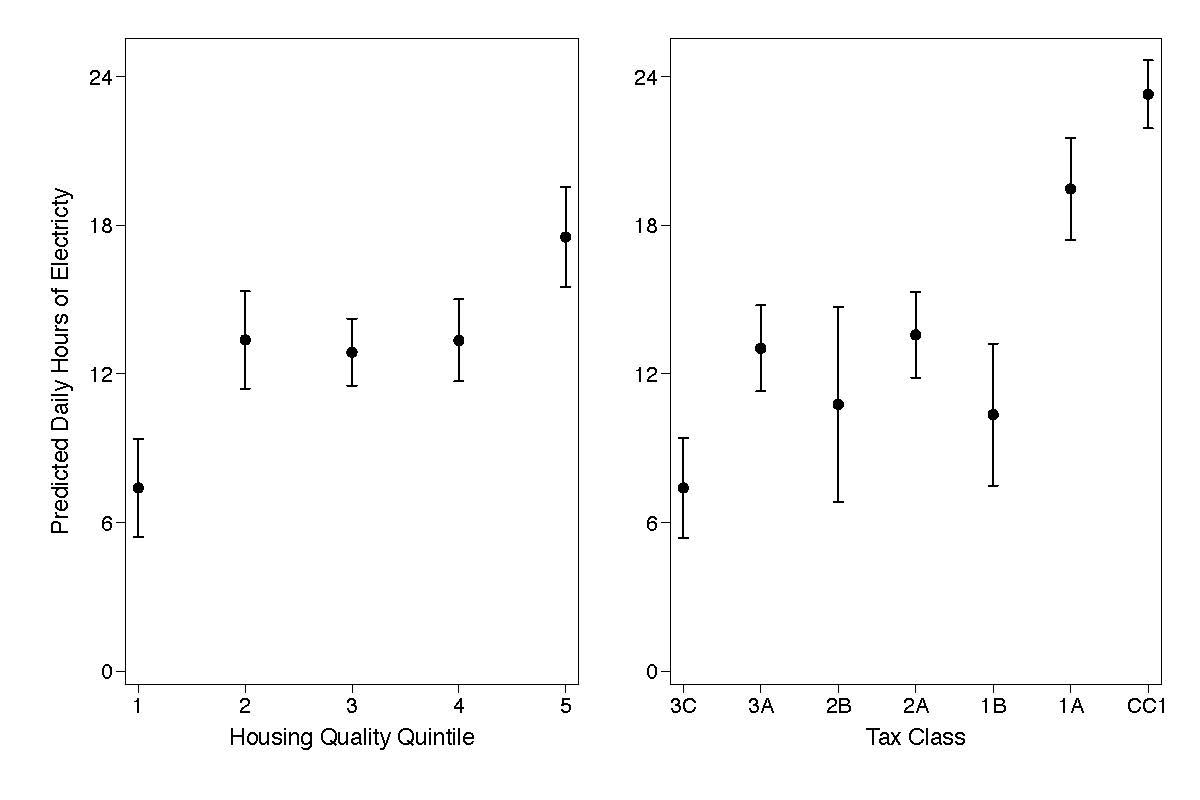

We conducted an analysis to see whether the ECG was following its schedule. Using social media and text messages, we collected data on electricity availability for 32 of Accra’s neighbourhoods over a two-week period. We then matched this data to two measures of wealth – the neighbourhood’s local tax rates and a measure of housing quality in the area.

Our research showed that blackouts were not following the ECG’s schedule of equal cuts. While the poorest neighbourhood in our sample received an average of about 7 hours of electricity a day, the richest neighbourhoods received between 18 to 23 hours of electricity a day.

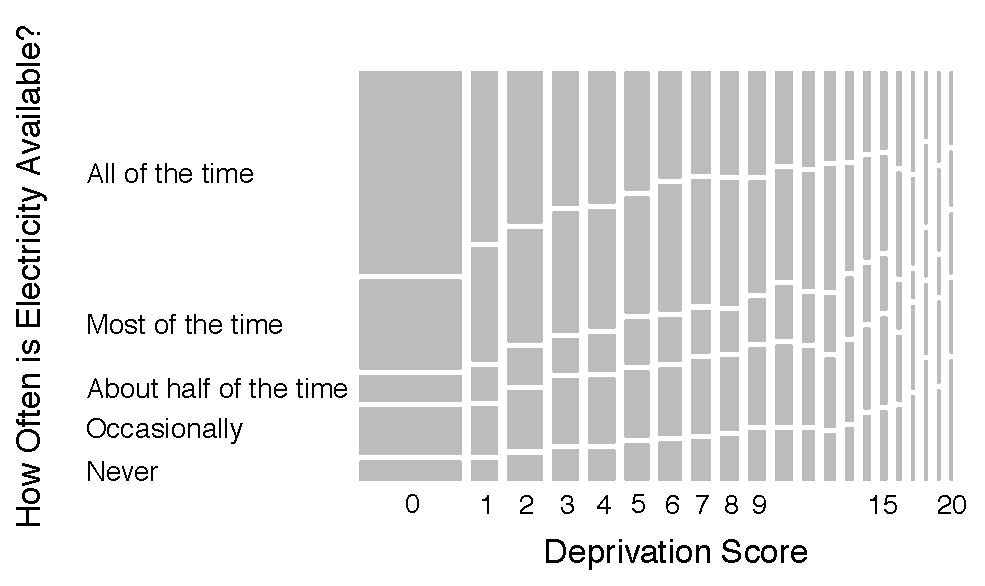

We also tested to see whether this result generalises using survey data on over 30,000 people from across 36 African countries. We showed that of people with a connection to the electrical grid, poorer people experienced less reliable electricity than richer people. This result holds within countries and within regions within countries. Like in Accra, across Africa poorer people receive less reliable grid-powered electricity than richer people.

While we have clear evidence describing the fact that poorer people receive less reliable electricity, we do not have clear evidence explaining why this happens. A few explanations seem plausible. First, it could be that the ECG is targeting places where they think they can earn the greatest profit and that these are richer areas with higher demand and marginal tariff rates. This logic was laid out by Dr Charles Wereko-Brobby, former Chief Executive of Ghana’s Volta River Authority, who said that ‘the only schedule that matters is where ECG thinks it will get paid’.

It could be the case that financially better off people are better able to lobby politicians and in doing so shelter themselves from power cuts. It could also be that governments under-invest in infrastructure in poorer parts of countries, and so even if the government does not directly want to aim cuts to poorer places they still occur more frequently there because people in better off areas have more reliable and better maintained infrastructure.

Regardless of the mechanism producing the results, a sad irony of the findings is that the people least likely to experience power cuts are the relatively well-off people who are most likely to own generators or other backup power sources. Our work also cautions people against viewing energy poverty as simply being a matter of extending the electrical grid to areas where it is lacking. Grid extensions can be important, but it is also important to understand how to equitably keep the lights on for those who are already on the grid.

Photo by natsuki on Unsplash.