Sexual minorities in Nigeria use Twitter to contest the invisibility Nigerian society forces upon them. By examining the linguistic advocacy of ‘coming out’ and ‘reaching out’ on the social media platform, users can establish a sense of community while challenging heteronormative values by asserting individual and group sexual agency.

While the 2014 Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act in Nigeria is often represented as a reaction to Western ‘invasive’ tendencies, particularly in the face of President Obama’s threats of sanctions in the face of the opposition to the legalisation of homosexuality, the Act validates the country’s homophobic tenor. For many young Nigerians, especially males, queer sexuality is foreign and its visibility must be censored. Thus, heterosexuality is prescribed as normative while any form of sexual deviance must be closeted.

Unsurprisingly, the tropes used to deny and denigrate queer sexualities find their roots in patriarchal constructs which harness moral, religious and cultural values in the ‘othering’ of queer sexualities. Even more ironical is the fact that much of these homophobic attitudes are offshoots of colonial moralisation while the legal codes hark back to British anti-homosexuality colonial laws.

These legal impediments further serve as validation for homophobic attitudes. Such attitudes are unsurprisingly commonplace in Nigeria, indicative of the stifling public lived experiences of Nigerian queers. They also serve as reinforcement of Claudia Böhme’s reference to the typification of homosexual desires as ‘a sickness, a bewitchment, and part of an occult economy’.

In my recent article I explore how the Nigerian queer community has appropriated the digital space, via social networking platforms, as a point of refuge from the performative inhibitions and limitations of the Nigerian physical space. For most Nigerian queers, relocating or seeking asylum abroad has been (and continues to be) the major alternative to living a lifestyle of pretence in line with Nigerian society’s heteronormative expectations. However, with Internet-enabled access to digital spaces, people of queer sexual orientation actually contest the negative representations of their sexuality while also affirming their identities.

I examine linguistic advocacy in coming out and reaching out narratives by Nigeria queers on Twitter. By coming out, I engage how Nigerian homosexual Twitter users can reveal their sexual identity and establish a sense of community with other people of queer orientation. Reaching out, on the other hand, is explored by paying attention to how the queer community educates and engages with the larger society vis-a-vis issues surrounding acceptance. To achieve the research aim, I collected tweets by Nigerian Twitter users through keyword searches. I analyse these tweets with corpus linguistic tools and critical discourse analysis.

Why Twitter?

Social networking platforms are increasingly popular across demographics and national borders, providing users the opportunity to connect and share experiences with other users. Twitter is one of such very active platforms used by Nigerians.

On Twitter, Nigerians discuss different political and social issues, such as calling out government actors, contributing to trends/issues of national or global importance and, of course, expressing their opinion on a contentious topic like queer sexuality. Eve Shapiro, for instance, acknowledges that online social networking media constitute domains where everyone, including the non-elite, can engage in socio-political advocacies and activism, towards having real-world implications and changing their social realities. Specifically within the context of amplifying queer voices, Kenyan scholar Evan Mwangi (2004) has argued that cyberspace is increasingly deployed by users to represent homosexuality as an identity and cultural signifier. How then does the Nigerian self-identified queer male community signify coming out online? How do they wield language in their public advocacies?

Contesting gender ideology and affirming queer agency

In the narratives I explored, there are obvious contestations of prevailing gender ideology – that which identifies and elevates heterosexuality as the norm while denigrating queer sexualities. An interesting finding was that many of the commenters showed comfort in presenting themselves as homosexuals. These were realised through clear statements, the use of positive queer-identifying names and the pride flag in their profiles, and more.

Because coming out has never been straightforward, experiences varying based on social context, time and place while predisposing people to stress, isolation and rejection, through these narratives Nigerian queer people humanise themselves in the discourse and represent themselves as being like any other Nigerian. They further express the reality of queerness being present throughout Nigerian society. An instance is the tweet below:

“@iam_modashe (2019, October 6): The bank executive in the board meeting The Playboy flirting with the ladies at the bar The quiet fuel attendant punching the numbers The security guard at the mall The OAP at your favorite radio station, filling the airwaves The NURTW chairman of your area #WeAreMany”

Coming out online constitutes self-acceptance and its public expression. In the message by @iam_modashe, while the tweet’s author comes out to publicly acknowledge their sexuality, the hashtag #WeAreMany is used as a marker providing the tweet visibility and aligning it with a discussion/movement attesting to the many other people yet to publicly divulge their sexuality. Through their online revelations, these commenters serve as energisers to embolden other queers to accept and enact their sexual personalities. Other members of the community also reinforce these decisions by providing textual acclamations and positive feedback.

In addition, there are advocacies which seek to draw the attention of family and the non-queer community to the burden society places on the performance of queer sexuality, as expressed below:

“@kikimordi (2019, December 26). It’s almost 2020 & same sex marriage is still illegal in Nigeria. Like two people (of the same sex) can love themselves and want to build a family for themselves just like you & I but can’t because it’s illegal for them.”

This tweet puts into focus the discriminatory practices that make queer relationships and unions legally impossible. By drawing attention to their plight, these queer users and their allies attempt to co-opt and incorporate the support of larger society into changing narratives and realities.

Allied to these textual validations are the use of Twitter conventions like retweets and hashtags. While retweeting involves relaying or rebroadcasting another user’s tweet, it also ‘contributes to a conversational ecology in which conversations are composed of public interplay of voices that give rise to an emotional sense of shared conversational context’. Combined in these narratives, these Twitter conventions help to topicalise queer narratives, signal agreement with the queer tweet authors, amplify or spread the tweets to a larger audience and show support with the tweet writer.

Through their linguistic representations and advocacies, the Nigerian queer community online also rejects the perception that non-heterosexual orientations are ‘mere imitations of western gay life’. Instead they accentuate the naturalness of queer sexuality as sexual orientations which had always existed within many Nigerian societies. To reinforce the normalisation of their sexual orientation, these commenters indicate that Nigerian society problematises the wrong issues.

“@OmogeDami (2019, December 28). Nigerians have bigger issues to attend to, but your government left those issues and made out time to criminalize homosexuality. You people are ridiculous.”

“@RachaelCapaldi (2019, December 29). It doesn’t even make any sense. Pedophiles in the north are allowed to roam free, politicians are allowed to loot our collective wealth but two consenting adults would be put behind bars because they want to love eachoda. Btw this law doesn’t apply to the rich elites of Nigeria.”

In the tweets above, the commenters validate the marginalisation of queer sexuality and opine that the censorship of their sexualities is a clear indication of misplaced priorities. Nigeria certainly has genuine problems like corruption, infrastructural decay and under-development which require urgent attention. It is, however, not uncommon for politicians and religious leaders to divert attention from their inadequacies by scapegoating people of queer sexuality.

Taking control through self-representation

The contestation of judgemental narratives by the queer community is targeted at public visibility and acceptance, as well as the liberalisation of the normative sexuality spectrum. These pro-queer commenters attempt to realise this first through taking control through self-representation, in which they control their coming-out narratives and make concerted attempts to confront the menace of homophobic cyberbullying.

These acts are particularly interesting because more Nigerian queers seem to be at ease with ‘coming out’ online, especially on Twitter, with respect to their sexuality and seem not to mind revealing their identities. Moreover, these identities are two-way: some users express their real identities (sexual as well as physical details like locations) while others only indicate their sexual identities. Both categories of users, however, display comfort with their personality and signal their readiness to navigate homophobic tendencies evident on online platforms. In addition, these commenters channel efforts at reaching out to various segments of the larger society as a form of advocacy towards societal and institutional acceptance. They appropriate digital conventions available on social media platforms towards in-group affinity while also making legitimising outreaches targeted at the family and other non-queer people.

Explorations of the representations of homosexuality are apposite within the African contemporary social space because they ‘fill in the gaps and silences’ that have shrouded discourses around this topic. Through these, one identifies and humanises the lives and existence of marginalised subcultures. In their online engagements, the marginalised Nigerian queer community recognises and employs digital media as a ‘new public space for political discussion…[for] political underdogs’.

In the narratives analysed, what stands out is the assertion of individual and group sexual agency. This agency is negotiated from complex positions, and with knowledge that marginalised communities can only access power through resorting to resistant modes. I thus conclude that these Twitter-based engagements and representations contribute to and assert queer advocacies, in a bid to occasion ‘sexual affirmation and emancipation in African societies that are socialised in heterosexual values and which ridicule and shame the idea of difference and ambiguity’.

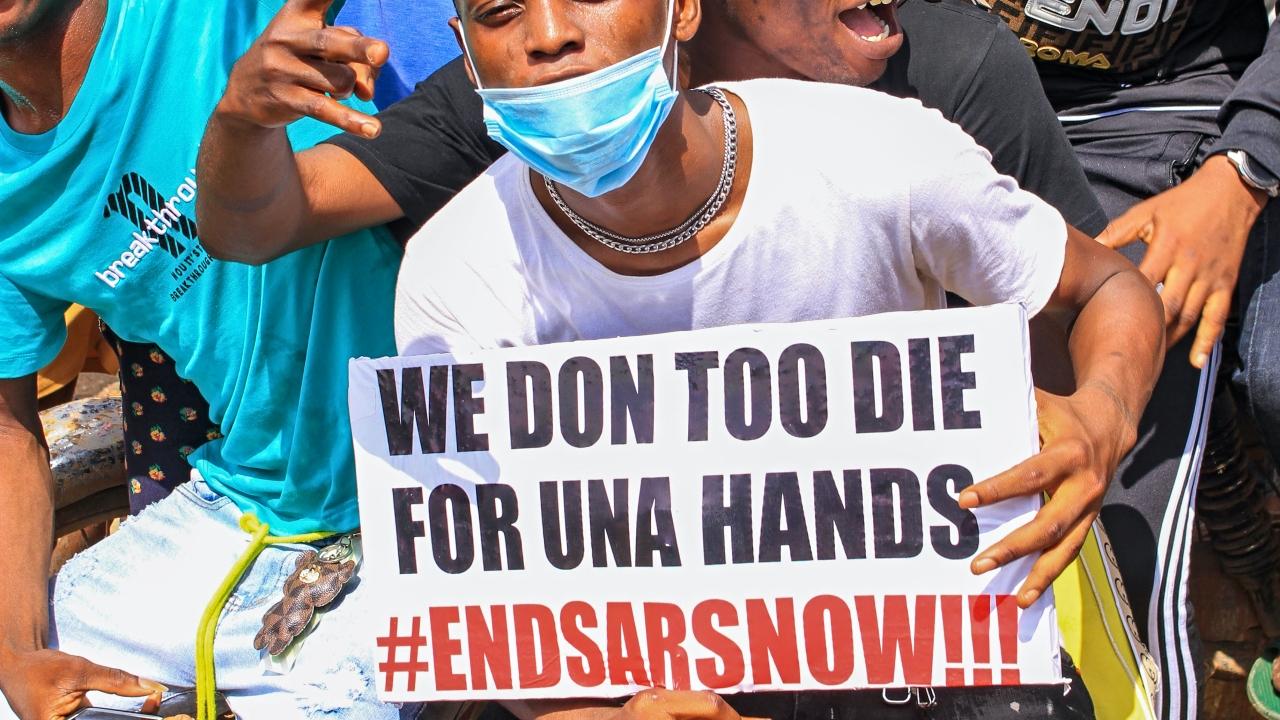

Photo by Benjamin Dada on Unsplash.

Incredible writing. So refreshing to see writing on pro-queer Nigeria that emphasizes the unique experience of queer life in Nigeria as opposed to a copying of Western queer culture.