There has been little research into the regulation targeting fake news and hate speech in Africa, and the role state institutions play in shaping them. With tech giants relatively inactive in moderating local content on their platforms, governments are using a mix of technological and legal content regulation.

The proliferation of fake news and hate speech in Ethiopia’s war, and the spread of fake news related to the COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa and Nigeria, illustrate the potential harms of online content in Africa and the need for its regulation. Discussions about regulating fake news and hate speech online, however, mostly take place in the global North. In our article, we highlight that the regulation of fake news and hate speech is a pressing issue beyond this region.

Tech giants like Facebook or Twitter have remained relatively inactive in moderating local content in Africa. In the absence of content moderation by content providers themselves, African governments have developed a range of strategies to regulate fake news and hate speech. But what are these strategies? And how do they vary across different regimes?

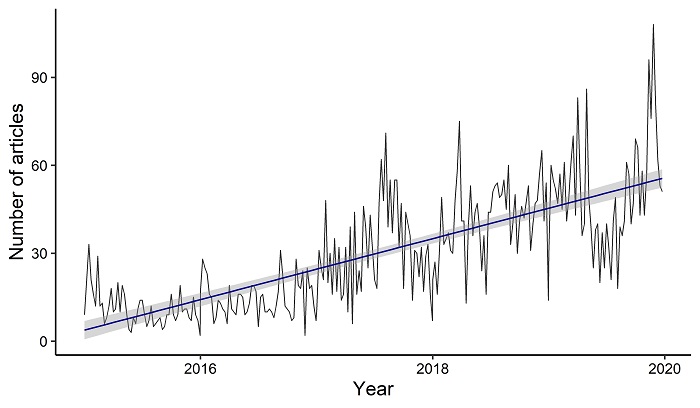

Increasing news reporting about online hate speech, misinformation and disinformation, illustrated in figure 1 below, highlight the salience of these questions. Besides, news reporting also offers an avenue to study the regulation of content. We sourced nearly 8,000 news articles from Factiva to identify state-led regulatory strategies in Africa and evaluate which regime characteristics shape the choice of strategy.

Two approaches to regulate fake news and hate speech

Based on a quantitative assessment of the news articles, we found that African governments use two prominent regulatory strategies to tackle fake news and hate speech, namely technological and legal content regulation.

Technological content regulation includes censoring or blocking access to content, to prevent the spread of fake news or hate speech. Critics argue that governments often use fake news and hate speech as a pretence to prevent opposition actors from accessing specific content. A news article about the internet shutdown in Cameroon underlines this problem:

‘[Cameroon] endured at least two Internet cuts since January last year with government saying the blackouts were among ways of preventing the spread of hate speech and fake news as the regime tried to control misinformation by separatist groups in the Northwest and Southwest.’ (The Citizen, 2018)

Legal content regulation includes discussing, drafting and passing bills to regulate fake news and hate speech, as exemplified by a news article covering legislation in Kenya:

‘Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta signed a lengthy new Bill into law, criminalising cybercrimes including fake news … The clause says if a person ‘intentionally publishes false, misleading or fictitious data or misinforms with intent that the data shall be considered or acted upon as authentic,’ they can be fined up to 5 000 000 shilling (nearly R620 000 [43′865 USD]) or imprisoned for up to two years.’ (Mail & Guardian, 2018)

How regime characteristics shape regulation

When and why do governments choose between technological and legal ways to regulate fake news and hate speech? Using data from the Varieties of Democracy dataset, we evaluate which regime characteristics are correlated with a higher salience of news coverage of technological and legal regulation.

First, we find that regimes that typically restrict media freedom are more likely to use technological regulation, and are less likely to use legal regulation, according to news reports. This suggests that those rulers who have strong incentives to prevent the production and spread of content are more likely to use technological means to regulate so-called fake news and hate speech.

Second, we find mixed evidence that institutional constraints on the executive shape the choice of regulatory strategy. Specifically, we find that regimes with stronger legislative constraints on the executive are not featured more prominently in news coverage about either technological or legal regulation. This suggests that strong legislatures may prevent a government from blocking internet access. However, strong and independent legislatures do not necessarily push for legislation tackling fake news and hate speech.

Better understanding legislation on fake news and hate speech

While our findings suggest that regimes repressing media freedom are more likely to use technological means to prevent fake news and hate speech from spreading, it is less clear how government institutions like legislatures and courts shape content regulation.

Notably, regimes without strong legislatures are also pushing for laws to regulate content. This may reflect the increasing importance of law-making as a political tool of power consolidation and illiberal practices, also known as ‘autocratic legalism’. Especially in more illiberal African countries, laws are often targeted at individuals and criminalise the production and spread of fake news and hate speech. In some cases, laws are explicit, like Kenya’s Computer Misuse and Cybercrime Act that criminalises the ‘publication of false information in print, broadcast, data or over a computer system’ (2018, Art 22, 23), directly referring to the publication of ‘hate speech’. In other cases, legislation is more indirect: for example, in Tanzania, Lesotho and Uganda, laws indirectly prevent people from sharing content online, either through fees on social media use itself, or fees that are required from online bloggers.

These examples underline that we need to better understand the different types of legislation targeting fake news and hate speech, and the role state institutions play in shaping them.

While criminal sanctions can be an effective way to counter hate speech, it is necessary to find an appropriate balance between censoring content and respecting freedom of expression. In turn, the current prevalence of state regulation as the solution to fake news and hate speech points to the need for multi-stakeholder approaches across continents.

Photo by Darlene Alderson from Pexels