To mitigate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, the DRC introduced new regulations on movements across borders, with significant disruptions to small-scale traders’ informal operations. In response, these traders in the eastern provinces forged new collaborations. LSE Research Officer Jonathan Bashi writes that ‘groupage’ among the traders could accelerate the formalisation of small cross-border trade in the region, and increase much-needed customs revenues.

This post is part of the African trade policy series based on research at the African Trade Policy Programme hosted by the LSE Firoz Lalji Institute for Africa.

The pandemic, and governments’ measures to contain it, have affected trade across Africa, including in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). While new regulations on movement across borders typically disrupted and slowed the operations of larger-scale traders in the country, they had a far more serious negative impact on micro and small enterprise traders and transporters who engage in trade across borders informally.

But the pandemic also caused a positive development. To mitigate these effects, small traders in Eastern DRC began working together and buying goods in bulk – a shift in practices that has the potential to both facilitate and accelerate the formalisation of small cross-border trade in the region.

The fragility of informal cross-border trade

The DRC’s economy is heavily reliant on external trade, including informal trade, which focuses mainly on agricultural and livestock products. Several of the country’s border cities and towns depend on imports from neighbouring countries. This is the case for most towns in the Eastern provinces of the DRC (including Ituri, North Kivu and South Kivu), where a large majority of local markets are supplied from neighbouring countries such as Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi.

Local markets in this region are supplied by traders working micro and small enterprises across borders (or ‘small-scale cross-border traders’), most of whom are women, grouped into cross-border traders associations (ACT – Associations des Commerçants Transfrontaliers). Before the pandemic, these small-scale cross-border traders were used to sourcing goods from neighbouring countries by transporting them on their backs or on the bicycles (adjusted wheelchairs) of disabled transporters, who offered transport services at the borders.

This mode of operating has proved to be limited and inefficient, as traders were only able to transport small quantities of goods, which were often undeclared. This type of trade is often coined ‘informal cross-border trade (ICBT)’, referring to the fact that most of the traders lack registration as formal business owners and the volume of goods that they transport is so small that it is not generally captured by official data. But this type of trade is not illegal, given that most small cross-border traders go through official border posts and often follow official clearance procedures for their goods. However, operating informally during the pandemic made small cross-border traders particularly vulnerable to harassment by rogue border officials, especially on the Congolese side of the border, who also imposed on them illegal taxes.

The restrictive measures imposed by the government at the start of the pandemic, including border closures (except for goods transported in appropriate vehicles, such as those motorised), as well as health checks (including temperature checks, COVID-19 tests and handwashing), had devastating effects on small cross-border trade. These new measures significantly restricted the movement of people across the borders, which resulted in additional costs as well as delays in the delivery of goods. Most small-scale cross-border traders in Eastern DRC were no longer allowed to carry out their activities at the borders, thereby losing their businesses and livelihoods.

The informality of their activities has also prevented small cross-border traders from taking advantage of the facilitation measures put in place by the government to mitigate the negative effects of COVID-19 on the country’s economy. These measures include a three-month exemption of VAT on the importation and sale of ‘basic’ goods and a financing scheme from the Industry Promotion Fund (FPI – Fonds de Promotion de l’Industrie). Mainly aimed at large-scale traders, these measures did not address the challenges faced by small-scale cross-border traders.

‘Groupage’ and the push for the formalisation of small-scale cross-border trade

To adapt to the challenges posed by the pandemic and the government’s restrictive measures, some cross-border traders’ associations introduced a ‘groupage’ practice. Small cross-border traders, often all dealing in one particular type of good, would group together to buy goods in bulk from suppliers in neighbouring countries.

This practice organises the purchase, transport and delivery of goods in groups, using small trucks and vans. It has the advantage of allowing small-scale cross-border traders to significantly reduce the operational cost that, otherwise, would have been borne by each individual trader. In addition, the reduction in the number of small traders crossing the border (this being now limited only to representatives of their associations who are responsible for placing group orders), has also made it possible to significantly reduce the level of harassment and illegal taxation at the borders.

As a result, goods imported using the groupage method were more closely monitored by the customs administration than had previously been the case when individual small-scale traders were bringing them in bit by bit. This allowed the administration to better identify the flow of goods from small cross-border trade which, until then, was informal and, therefore, unrecorded and untaxed.

Furthermore, by facilitating a better monitoring of small cross-border trade, groupage also allows a more effective implementation of the COMESA Simplified Trade Regime (STR) in Eastern DRC. All neighbouring countries involved in this trade, such as Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi, are member states of the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA).

The STR is a trade policy measure adopted in 2010 by COMESA which targets small-scale cross-border trade. It introduced a customs duty exemption and simplified clearance procedures for low-value consignments (less than US$2,000) of applicable products. These products are included in several ‘Common Lists’, which are bilaterally agreed upon between neighbouring COMESA Member States, with goods to be traded duty free across their common borders under the STR policy.

The STR is designed to enable the traders to benefit from regionally agreed tariff reductions and exemptions when importing or exporting certain goods. It is meant to facilitate the formalisation of small-scale cross-border trade and to improve the performance of small-scale cross border traders within the region.

A better structuring of the flow of goods across borders allows customs administration at the borders to better identify goods from small cross-border trade and, thus, to apply the preferential tariff provided for them under the STR. This was practically impossible before the pandemic and before groupage, since the customs administration claimed to have difficulty in identifying the goods of small cross-border traders, given that they often moved in a scattered way and, sometimes, without resorting to official procedures for imports or exports.

The way forward for groupage in Eastern DRC

While the pandemic has further exposed the dependency of several towns in Eastern DRC on imports from neighbouring countries, it has also given the government of DRC a great opportunity to increase the country’s resilience in the face of more COVID-like disruptions. To move forward, the government should prioritise the adoption of several measures aimed at further fostering informal cross-border trade and tackling barriers to the free flow of goods across borders.

These include policies aimed at further supporting the formalisation of small-scale cross-border trade through groupage, with steps taken to facilitate quicker and more streamlined border processes for group consignments. This involves the simplification of the documentation process for goods under the COMESA STR, with the integration of the ‘Simplified Certificate of Origin’ into the Congolese customs software. Such a process would facilitate better calculation and application of preferential STR tariffs which, so far, are being done manually by customs officers, leaving room for human error and subjectivity.

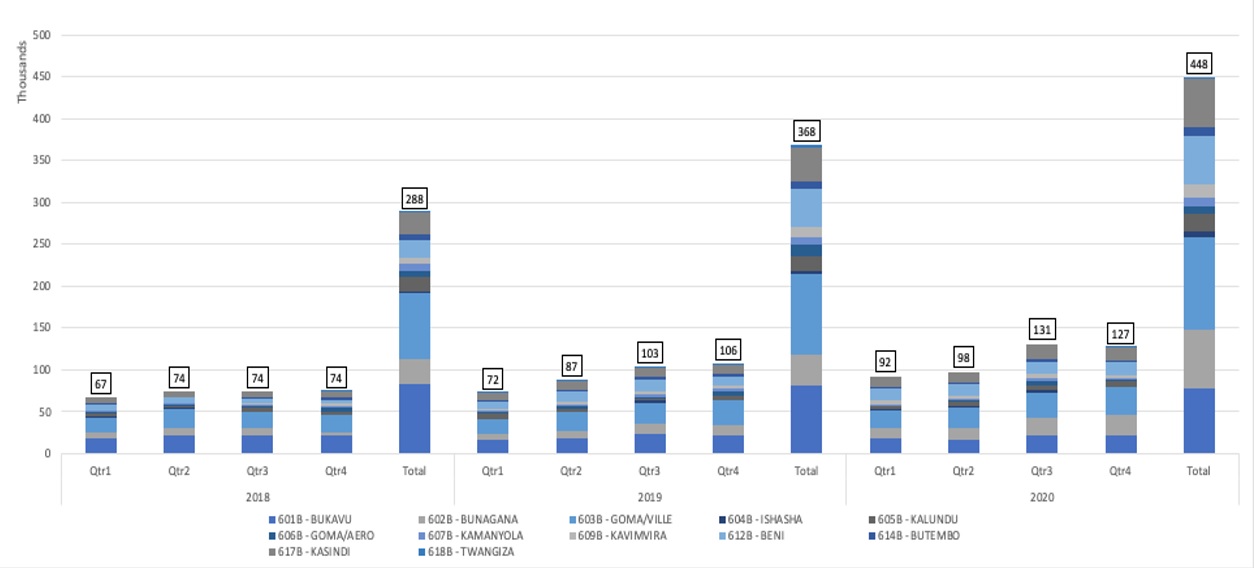

Trade data from the DRC Customs Directorate (Direction Générale des Douanes et Accises) seems to support this proposed course of action. Despite the pandemic and a steep fall in import volumes in Eastern DRC during the first quarter of 2020, an unexpected recovery took place in the second half of the year, and the region even recorded an impressive 22% increase in 2020 compared to 2019. The recording of goods from small cross-border trade, without a clear distinction with the goods of large traders, could explain the increase in the volume of formal imports in the second half of 2020.

While it has proven to be effective during the pandemic, the groupage method would be more effective if small-scale cross-border traders had easier access to digital payments at a low cost. Specific policies should be adopted to encourage the country’s financial institutions, including mobile money companies, to develop fast and low-cost digital solutions for cross-border financial transactions, which are targeted at micro and small enterprise traders.

A closer collaboration between state border agencies and cross-border traders’ associations could help design and implement measures aimed at better assisting small-scale cross-border traders, including disabled cross-border transporters. These measures could help promote greater access to finance to facilitate their current and new business activities.

The allocation of sufficient resources to border agencies could also promote better communication and coordination with their counterparts in neighbouring countries, thereby promoting safe and structured trade across borders. By contributing to the better recording of trade volumes, much needed customs revenues could increase.

Photo by Random Institute on Unsplash.