Half a year after the 2021 coup in Guinea, the military junta has attempted to control the National Bank’s foreign-stored gold reserves. Relatedly, a tug-of-war has ensued over the financing and resources allocated to democratic parties in view of promised elections. To transition into a successful democracy, Roland Benedikter writes that a key challenge is therefore reordering natural gold and resource management, linked to effective financial and infrastructural development needed to hold fair elections.

Since the 5 September 2021 coup, the reshaping and refoundation of Guinea’s economy, including its underlying infrastructure and participatory mechanisms, stands at the centre of the ruling military junta’s declared goals. Guinea is classified as a ‘low income’ country by the World Bank with the 122nd largest GDP, and ranked 165th of 196 countries for GDP per capita. This makes its ‘real economy’ for daily livelihoods one of the poorest in the world. At the same time, economic freedom remains limited. The nation is placed the 129th freest worldwide and the 25th among 47 countries in the sub-Saharan African region, and 156th in the Ease of Doing Business ranking. Nevertheless, the African Development Bank considers Guinea’s post-Covid-19 outlook positive, with growth forecast at more than 5% in 2022 and ‘sustainable’ debt expected to gradually shrink to 2.3% in the absence of unexpected events.

Responsibility for the country’s mixed economic outlook have been largely attributed to former governments, among them the more than a decade-long rule of former President Alpha Condé (2010-21). The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative has long illustrated that the extraction of raw resources on average account for 97% of Guinea’s export revenues. One of the potentially richest African countries, blessed with natural resources that include a third of the world’s bauxite reserves and significant gold, diamond and oil deposits, still nonetheless remains one of the poorest. Selling raw resources instead of more sophisticated products made from them indicates an underdeveloped and poorly differentiated economic structure.

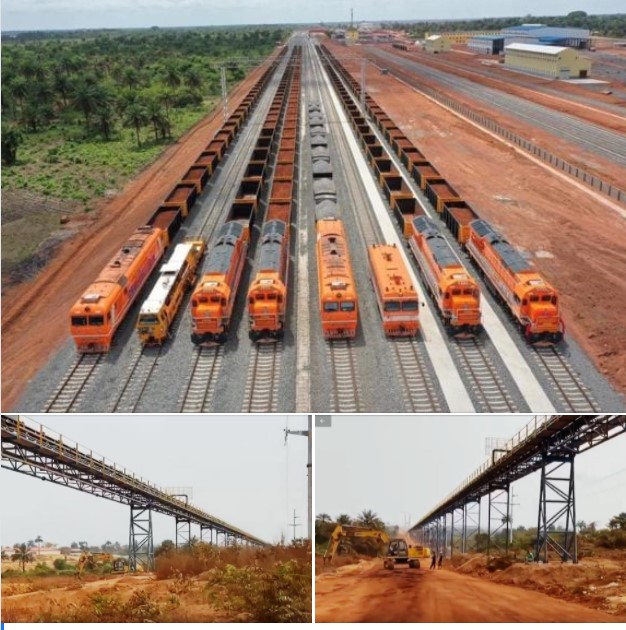

Large parts of the extraction industry are also in the hands of non-democratic foreign powers and investors, notably China and Russia. Meanwhile, critical infrastructure, such as railroad transportation, has been built for foreign extractive industry actors rather than the mobility of the broader population.

The raw resources export trade feeds the National Central Bank with currency. In this context, Guinea’s National Bank (Banque Centrale de la République de Guinée, BCRG) remains the core financial instrument and de facto controls the country’s economy. It therefore came as a surprise when Guinea’s young military junta in December 2021 sacked the Governor of the Central Bank and held him in custody. The reasons shed some light on the country’s process of transition after the coup.

At the beginning, the military junta, the National Committee of Reconciliation and Development (Comité national du rassemblement et du développement, CNRD), seemed to work well with the Governor of the Central Bank, Lounceny Nabe, who shares the same Malinké ethnicity. This changed after a few months. His criminal interrogation focused on a case of 12.14 Guinean tons of gold held by the Belgian precious metals and storage company AFFINOR. In March 2021, still under the rule of Alpha Condé, Guinea signed a contract with AFFINOR to refine and store gold for its Central Bank to meet the country’s currency needs. When Guinea needs currency, AFFINOR sells the gold and sends the returns to the bank. After nine tons of the overall holdings are said to have been sold, 3.14 tons are expected to be left in Guinea’s AFFINOR account.

The new government is now trying to secure this national fortune. It is unclear whether this is purely to take the money itself, or to reclaim the country’s most important national resources to give it back to the people. But problems accessing it are allegedly due to complications with foreign authorities. Since February 2022, Guinea’s account at AFFINOR was frozen for a lack of documentation. The BCRG was unable to prove the origin of this gold of which a part, 1.8 tons, apparently came from Dubai. Police in London partially ascribed money laundering to the sale of the gold. As a result, there are rumours that a compromise punitive fee of $37m may be paid in the coming months, an amount that AFFINOR wants sponsored by the Guinean state. This could explain why the junta wants to repatriate the gold in a hurry. Yet based on the contact terms, AFFINOR said that it would rather pay the currency value than the gold itself, which it believes to respect the contract. The junta believes, however, that the current currency value is less valuable than the gold.

As a reaction, the military could bring charges against the former governor of the BCRG. This would increase pressure on AFFINOR to return the gold, since its close cooperation with an indicted Lounceni Nabe on corruption charges would suggest the company benefited from a potential crime. Moreover, the local representative of AFFINOR in Guinea, Mamadi Condé, seems to have fled to Sierra Leone. He comes from the same prefecture as Nabe.

Consequences for Guinea’s democracy

The gold case has repercussion for Guinea’s transition to democracy. Much depends on how financing democratic parties will be carried out and what freedom they will receive to further evolve. While some parties are still in the process of accreditation, others are planning meetings and voter mobilisation ahead of yet-to-be dated elections, to take the political temperature, capture people’s motivation, hear voters’ concerns and to listen to suggestions.

But some newly founded party movements still need to set up bank accounts and receive the payments that state authorities owe them, according to Guinea’s party financing rules. Other parties are occupied by establishing their infrastructures. For example, for the capital Conacry and the 33 prefectures, a fully functional party needs at least 50 working computers, printers and telephones, as the experience of previous elections have shown. It may also need vehicles for party activists and the leadership to deliver electoral campaigns. Party activists have been collecting materials and machines from volunteers, relying on those who want to help. But financial support by the state authorities remains crucial.

Here is where the circle between gold and democracy is completed: whatever the development of the political landscape and the outcome of potential elections, how Guinea’s gold and other resources are produced, managed and translated into state finance must firstly become more transparent through party finance and electoral laws if democratic parties are to participate in the nation’s resource wealth. It is for the sake of citizens’ emancipation.

The issue of reforming the mining, extrapolation, export and storage of Guinea’s gold and other precious metals is serious also from an international perspective. If Western nations are not careful, in 20 years their industries will no longer have access to sufficient raw materials to maintain their position as industrial lead powers. Among other factors, this could contribute to a decline in global democracy. China has already secured some of the most important extraction and development sites in Africa, and so has Russia. Guinea’s huge reserves of precious and rare earth metals, which in the pandemic era have been in short supply, are in high demand.

Establishing a working, participatory democracy to use resources for the common good and redistribute profits justly among citizens by investing them in infrastructure for all, and in the flourishing of democracy, is perhaps the most urgent challenge for a society in transition. Furthermore, the reorientation of Guinea’s financial, mining, industrial and economic policies towards open societies, away from authoritarian actors like Russia or China, is in the best interests of both Guinean citizens and Western democracies.

Photo by Tom Fisk from Pexels.