Conversations on how to prevent and maintain zoonotic outbreaks often focus on the role of vaccines and mitigation measures. To address disease transmission to humans in the long-term, however, means understanding the underlying drivers. An effective approach will mean acknowledging how large development projects and poverty forces people in Africa into areas with increased wildlife exposure.

This article is part of the series “Rethinking zoonoses, the environment and epidemics in Africa”, which examines the effect of changing relationships between human, animal and environmental health on epidemic risk.

Zoonoses – those “apocalyptic” diseases jumping from animals to humans – constantly break out in Africa and often with a huge human toll. Some of these diseases are fairly recent phenomena, such as Rift Valley Fever (mainly transmitted from livestock through mosquitoes), HIV and Ebola – the latter both originating in Africa’s tropical forests. Others such as Trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness), which is found in Southern, Central and Eastern Africa, have long been known. Whatever their history, these diseases can conjure enormous fear.

To many Africans, these diseases are considered a sort of witchcraft, which kill both good and upright people in ways dramatic and mysterious. Narratives that Ebola, HIV and other recent diseases are the product of European witchcraft targeting innocent Africans are as widespread as the diseases themselves. A popular and enduring version of this narrative is that such witchcraft is designed to eliminate Africans in areas of the continent’s abundant natural resources. However contested these allegations, there is no doubt that among historically marginalised Africans zoonoses remain witchcraft at large.

Contemporary African anthropologists note these epochal diseases’ selective nature. Only social groups entering into particular areas, and doing so at specific times, get sick from zoonotic diseases. Cattle herders and hunters, seasonally operating in the tsetse and wildlife ridden Zambezi Valley, are at risk from Trypanosomiasis in Zimbabwe. In East Africa, those who handle cattle and sheep in flooded areas are mostly exposed to Rift Valley Fever, which is transmitted by types of mosquitoes. In Ghana, only poor people encroaching into and operating in wild orchards contract Henipah virus from fruit eating bats. Clearly, not everyone living in “hotspot” disease areas gets sick.

What can be done to ensure the security of Africans from zoonotic diseases? Vaccines must certainly be encouraged, particularly among the various demographic and religious groups who regard them as extended European witchcraft to kill them. But vaccinations alone are insufficient to address the continent’s unique set of circumstances and why some groups are more at risk.

In recent years, exposure to diseases from wild animals has increased. Villagers in many areas are increasingly forced by poverty and inappropriate development projects to settle in places where disease outbreaks are more likely. This is unsurprising: the growing appetite by African governments and elites for huge development projects in irrigation, plantations or mining is associated with zoonotic disease outbreaks. Viewed as needed to promote African development and attract foreign currency, these state-led projects push people into risky development zones – or “disease landscapes” – against their will. Critics depict such phenomena as structural violence, leading to endless disease outbreaks in developing areas.

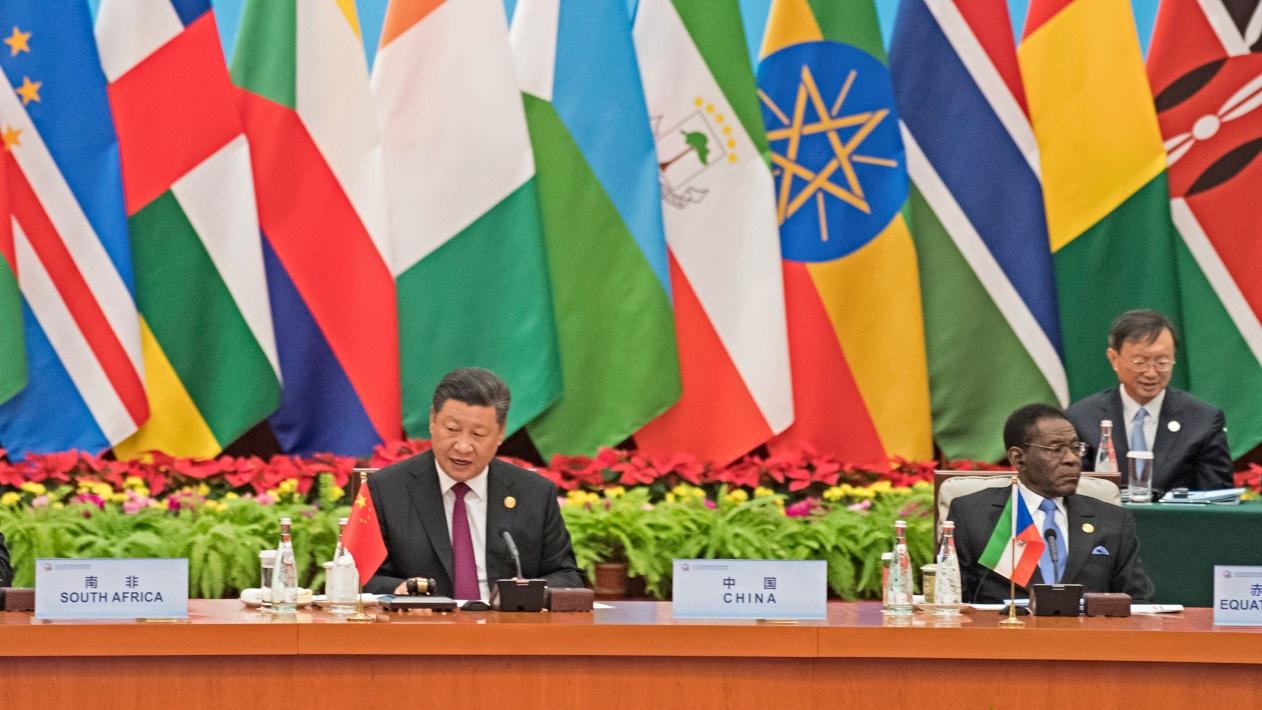

Effective disease prevention and management means avoiding such projects, often forced by an alliance of foreign investors and governments. Such efforts should work alongside tackling the poverty that drives marginalised people into forest patches with disease-potential. In Africa, this typically involves correcting colonially-induced land injustice and delivering land to marginalised peasants so they can produce food for themselves, rather than forage for roots and tubers in forests where disease carrying animals converge. Finally, there must be an effort to address the drivers of war and conflicts that displace people into forests replete with diseases. Resisting or countering the Western/Chinese big capital often behind these conflicts must be an enduring strategy to mitigate zoonoses on the continent.

Understanding that the eradication of zoonotic disease is not just a matter of tablets and self-isolation is essential. We must take seriously the underlying drivers that are mostly produced by political and economic forces often beyond the control of the continent and its people. Any initiative ignoring this principle will be seen as witchcraft with an evil goal: to extinguish Africans for the benefit of colonial powers.

Featured photo: Diafarabé Cattle Crossing. Credit: Bradley Watson: bradwatsonmedia.com. Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Hero photo by RF._.studio from Pexels.