Does humanitarian funding in Nigeria need to shift from the North East to the Middle Belt in line with conflict trends? Conflict databases reveal, rather, that the impact of violence on populations in the North East is worsening with an impending threat of famine. Nengak Gondyi argues that policy interventions must be informed by research anchored on often lacking data.

Nigeria’s conflict landscape is changing with new hotspots, new actors and new grievances continuously emerging. It is therefore important that some conflicts are not overlooked as peacemakers, governments and donors scramble to respond to others. At the same time, a poor response to one conflict does not mean that the response to another is disproportionately greater.

A recent article in Africa at LSE has questioned conventional wisdom on the severity of conflicts in Nigeria. Comparing the Boko Haram insurgency in the North East to the conflict between farmers and herders in the Middle Belt, the article concludes that communities in the later region have experienced more violence and killings, with the region hosting the highest percentage of internally displaced persons in the country. Based on data published in Small Wars and Insurgencies, this comparison is used to argue that the less debilitating conflict in the North East is receiving a greater share of needed humanitarian aid and policy attention. Consequently, the article warns that greater aid funding to victims of conflict leads to more research in the region, and more research in turn influences greater funding.

Available data in my research, however, suggests that the North East remains the most urgent emergency. The ACAPS database rates the Middle Belt conflict lower than the North East in terms of severity (3.2 compared to 4.2 out of a maximum of 5), impact (3.0 compared to 4.2) and humanitarian conditions (3.2 compared to 4.5). In terms of fatalities, from 2011 to the present the Nigeria Security Tracker has reported 8,265 deaths in Benue, Plateau and Nasarawa States compared to 43,095 deaths in Borno Adamawa and Yobe States. According to the IOM Displacement Tracking Matrix, there are 969,757 displaced persons in the North Central and North West compared to 2.17 million displaced persons across the North East.

Assessing the volume of humanitarian aid received in each conflict zone is not easy, but it is possible to state with some accuracy the needs that remain unmet for northeast Nigeria. The United Nation’s 2022 Nigeria Humanitarian Response Plan acknowledges 8.4 million persons in need in the region. However, current programming targets 5.5 million persons – if the humanitarian actors are able to raise $1.1 billion in funding. By mid-2022, only 14% of this appeal has been realised, and the UN has issued an alert that 4.1 million people risk starvation.

Further, prior to the recent UN famine alert, the Cadre Harmonisé framework estimated that between June and August 2022, 39 communities in the North East, four in the North Central and 39 in the North West will experience phase 3/5 (crisis) of food and nutrition insecurity. Only Borno State will have three additional communities on phase 4/5 (emergency), which is one phase short of famine. While some data on humanitarian aid programmes may be available, we lack the analysis and disaggregation to inform discussions of humanitarian need versus available aid across zones of Nigeria.

But if the conflict in the Middle Belt is more severe, is there evidence to suggest a greater receipt (or absence) of humanitarian aid correlates with an influence on research agendas? A causality is unclear, and greater data on research programming is needed.

Humanitarian support to victims of conflict is far from adequate across Nigeria. The country is presently ranked the 6th most terrorised nation globally, with its military deployed in peace support operations in all 36 states of the country. Meanwhile, 95 million Nigerians live below the global poverty line. Attempts to garner more support in aid of communities in conflict must be guided by a dispassionate analysis of the situation on the ground, even where establishing facts is challenging. Emphasising the severity of the conflict in one region should not depreciate the severity of conflict in another. It is essential that research informing funding policies maintains utmost fidelity to the available evidence.

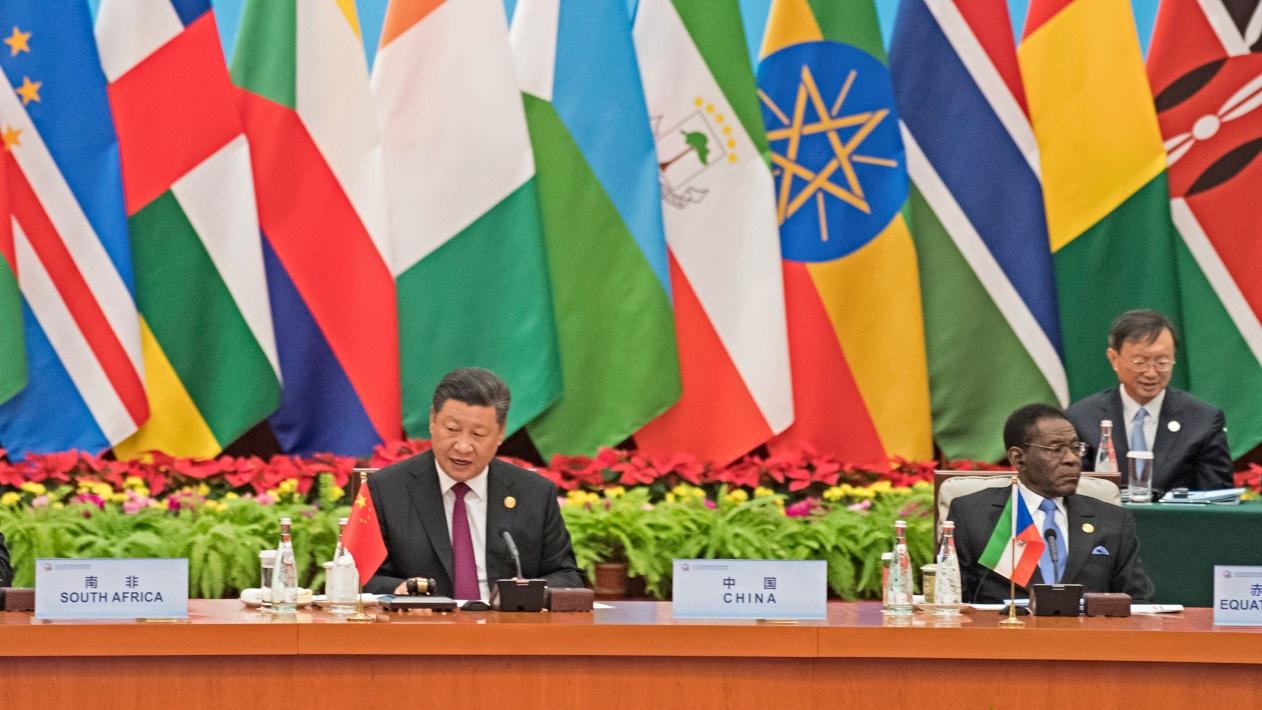

Photo: Oslo Humanitarian Conference on Nigeria and the Lake Chad region. Credit: WFP/Marco Frattini. Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Hello Nengak,

I can relate very well with the issues flagged in your article. However, I wouldn’t base the number of casualties and the degree of debilitating impact of conflicts on the humanitarian attention they receive, whether globally or locally. For me, beyond the numbers of casualties, there’s more on the expressed political position by both those seeking humanitarian assistance and those volunteering such assistance.

No doubt, the Northeast crisis is somewhat more intensed than the farmers/herders conflict in the North-central Nigeria., especially in contemporary sense. However, the seeming/obvious humanitarian attention being given to the Northeast is a function of voiced priorities of the government. At the inception of PMB administrattion in 2015, he requested development partners to focus their intervention in the Norteast. This is expected, given the challenges that the new government urgently needed to tackle.That policy pronouncement became the basis for the observed humanitarian attention by developmenr parters. For me, it has less to do with numbers of casualties and intensity, but more to expressed need by humanitarian intervention recipient – i.e. the Nigerian government.

Even in international politics, we’ve seen more debilitating conflicts played down for conflicts with less intensity due to hidden and/or open permanent interests

Thank you for the point, political positions influences funding, beyond number of casualties. I think the greater question now is, how then do we increase support for each area? I don’t know the answer, but I know that diminishing the criticality of an obviously critical problem would not be a great strategy. NB: Can we prove that X region receives more or less than it needs?

The first paragraph did all the justice necessary by affirming the need for validation by research and data. However, empirical research will further validate these claims as focus group discussions will bring to light the actual plight of human displacement and conflict in both regions, my two cents. Overall a great article, I got sold by how your claims were verified by data.

Thank you! I think that a lot of attention (at least reflections) focus on conflict emergencies and other problems (like floods that you know so well) easily get forgotten, we just sit and wait for the next!

The allocation of humanitarian funds isn’t just about the severity of conflict, is it? As you have shown here, it is also about the other facets of these complex emergencies. Far northern states experience periodic food insecurity at the best of times, so unsurprisingly the NE has a food crisis inside a war, whereas the Middle Belt remains fertile while insecure, so it’s not the same kind of problem.

Perhaps the fertility in the Middle Belt and the comparative stability of that region offers us an opportunity to farm our way out of crisis. But who is to say where the winds of conflict would blow next? Complex emergencies indeed. Thank you

You are right Nengak in the lens of the data that you have advanced. However, these datasets have their limitation.

First I think this should be less about shifting humanitarian support but more about prioritising other areas where violent conflict has deteriorated without necessarily cutting support in other places.

It is important to not lose sight of the politics of international aid. At the moment, North East Nigeria hits the mark and less of middle East and North West.

Less of humanitarian, development and peace building actors could impart on available data. For instance, anecdotal evidence will suggest more severity of the crisis in the North West and middle belt than we can find in any database.

Thank you for these. I think the anecdotal evidence is powerful enough, if collected in a systemic manner by credible interlocutors. One point that has re-echoed in the feedback I have received so far is the need to deeply reflect on what is wrong in each conflict setting in Nigeria (on its own) without trying to compare.

I know the data is limited and missing, we will learn more and reassess our thinking if new evidence emerges.

Great read!

I seem to particularly subscribe to the statement that greater aid funding to victims of conflict leads to more research in the North East, and more research, in turn, influences greater funding.

International humanitarian actors are more inclined to act based on available data backed by research. I also think other factors such as local and international media portrayal of conflict in Nigeria- which is mostly North East focused and the government’s priority statement on the issue cannot be totally downplayed.

This article is a call for more evidence based research into other conflict-affected regions in the hope of increasing funding and humanitarian aid.

I hope we find more evidence, there is surely not enough at the moment! In particular, I would like to see the data that links funding to research agenda. Thank you sir.

This is an insightful article, Nengak. You have clearly demonstrated that the differences in the conflicts and the impact index on the various regions explain the intensity of humanitarian response and development programs available therein. More research will certainly give guidance for determining the nature of conflict mitigation and humanitarian needs for the different regions; it will be more about providing evidence base for developing tailored interventions, equitable humanitarian response and development initiatives now than ‘quantity’. The gains will be enormous and holistic.

Thank you ma. I know one question you would love to see answered is “how does conflict in these two regions impact on women and girls”. I hope we find the data to answer important questions such as those.

I agree with the points you have raised, and in particular that there’s a need to match funding policies and their implementation with needs based researches.

However, I think there are others vested interests that ranks the NE as a more pressing need over the middles belt, maybe government interests.

But away from your OP, I will argue that the root causes for why these interventions are present in these regions can not be addressed by these humanitarian organizations, no matter their good intention, it’s largely still the job of the government, but I digress.

Beyond being accountable, and of course shelving whatever interests they have, the government of Nigeria must pay attention to socio economic effects that inadvertently affects every region by creating proactive policies needed by each region or state to address the societal challenges when these humanitarian organisation eventually leave.

One way to [attempt to] displace the vested interests is to find the evidence that shows their error. I know the Middle Belt is really affected by conflict, also the North West. I think the error emerges if we attempt to rank/compare them.

This is an insightful article, Nengak. You have clearly demonstrated that the differences in the conflicts and the impact index on the various regions explain the intensity of humanitarian response and development programs available therein. More research will certainly give guidance for determining the nature of conflict mitigation and humanitarian needs for the different regions; it will be more about providing evidence base for developing tailored interventions, equitable humanitarian response and development initiatives now than ‘quantity’. The gains will be enormous and wholistic.

Kudos Nengak. Last week I was in Maiduguri having an informal discussion with some humanitarian workers, as well as beneficiaries of humanitarian aid. Yes, humanitarian aid is helpful. One of the major crisis the north east must come to terms with, has to do with the fact that many communities are now used to east access to food, to the extent that they feel they have no business going back to the farm and wasting their energies cultivating or growing crops. How do we get communities back to farm? What’s the timeline for the delivery of humanitarian aid in circumstances that we see in the north east?

Aid dependency, that is indeed a big and a growing concern, particularly as the country side is not safe for people to resume agriculture. Perhaps the key to breaking the dependency is to devote more resources to secure livelihoods. Thank you sir.

Mr Nengak Daniel have made an in-depth analysis of regional humanitarian attention!. Indeed humanitarian intervention should also be channel to the middle belt, considering it’s location at the centre of Nigeria. When a state like , Benue, Plateau and Nasarawa are hit by terrorism, it means there exist no smooth road transportation network to the north east and the FCT. The humanitarian service providers should also focus in liberating the pains and casualty rate of the north central as the effects of crises in the North central is more devastating.