Communal disputes over local issues such as land use, cattle herding, and access to scarce resources are a leading cause of conflict around the world. Despite abundant evidence that peacekeepers limit large-scale fighting between armed groups, we know little about their ability to prevent more localised forms of violence. William G. Nomikos explains the conditions under which UN peacekeeping operations promote peaceful interactions between civilian communities in fragile settings.

On 22 February 2020, South Sudanese President Salva Kiir signed a peace agreement with his opponent, Riek Machar, pledging an end to the civil war that has killed more than 50,000 people since South Sudan declared independence in 2011. Kiir, a member of the Dinka ethnic group, made a show of asking his long-time rival for forgiveness. Machar, a member of the Nuer group, pledged to do his part by joining a unity government as vice president and integrating Nuer rebels into the national military of South Sudan. The United Nations (UN) peacekeeping operation in South Sudan supported the agreement, as did key regional powers.

Unfortunately, while Kiir and Machar may have reached an agreement in the capital, Juba, communities throughout the country remained on tension. In January 2022, an armed Murle militia raided cattle in a village in the Jonglei region—killing 33, including four children—in retaliation for an earlier cattle raid. Outbreaks of communal violence in South Sudan such as these throughout the country have killed thousands and displaced tens of thousands more since 2020.

Yet communal disputes in South Sudan do not always become violent. They are frequently resolved amicably, often thanks to the presence of the 10,000 UN peacekeepers in the country. For example, a company of Bangladeshi peacekeepers from UNMISS established a base in August 2020 in the rural town of Tonj following reports of communal disputes in the area. Their regular patrols have been remarkably successful at enforcing peaceful interactions between communities.

Communal disputes over local issues such as land use, cattle herding, and access to resources are a critical source of instability in contemporary politics. These clashes not only cause an immediate loss of life and forced displacement; they also spark new wars, lead to the formation and expansion of extremist organisations, and devolve into atrocities. To make matters worse, rising temperatures due to climate change have made land and water even more scarce, creating new disputes in countries ill-equipped to manage them.

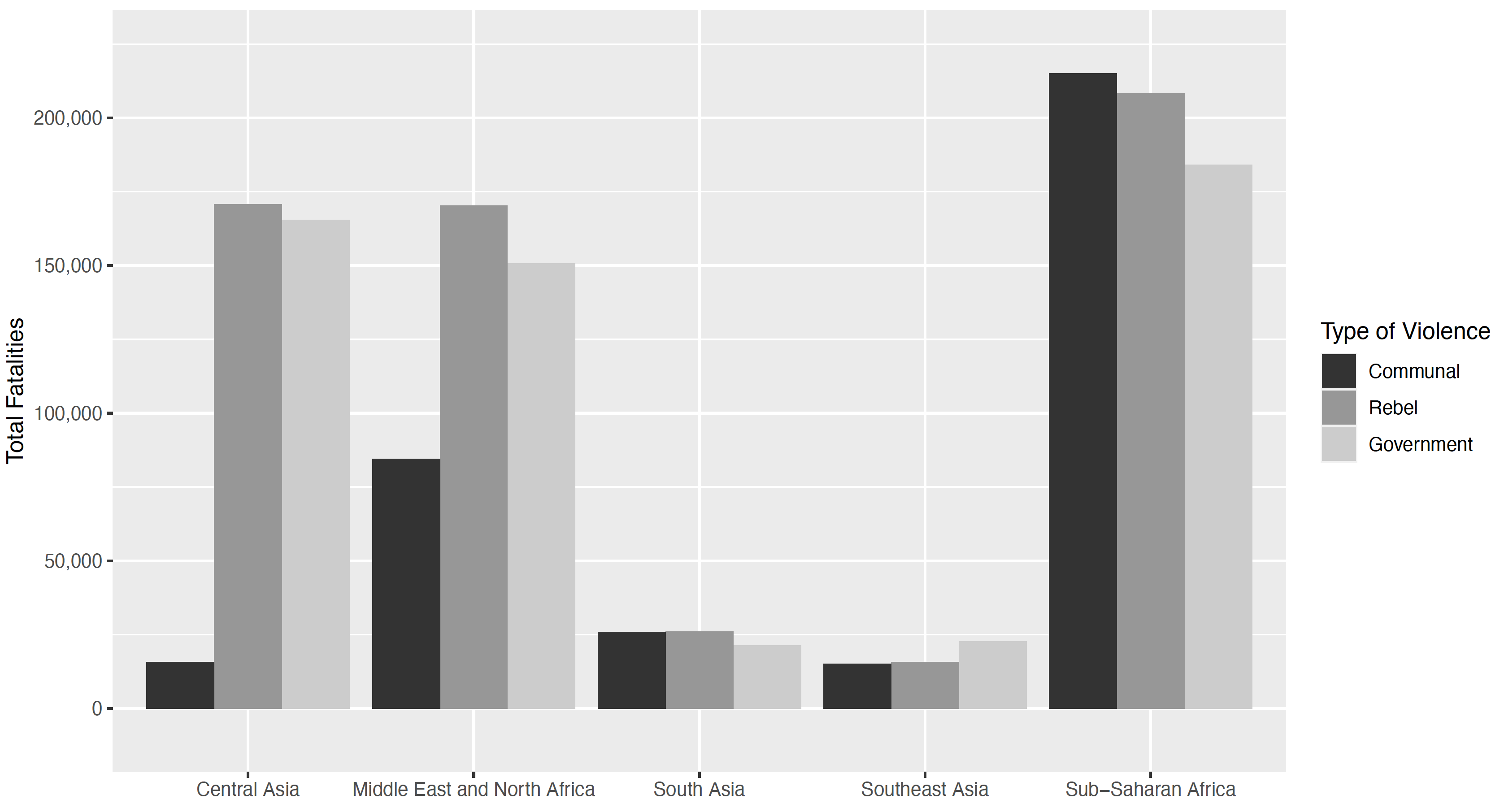

This is true not only in South Sudan but around the world, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. According to analysis by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) project, communal violence has killed nearly 250,000 people in the region since the turn of the century, more than violence from governments or rebel groups (See Figure 1).

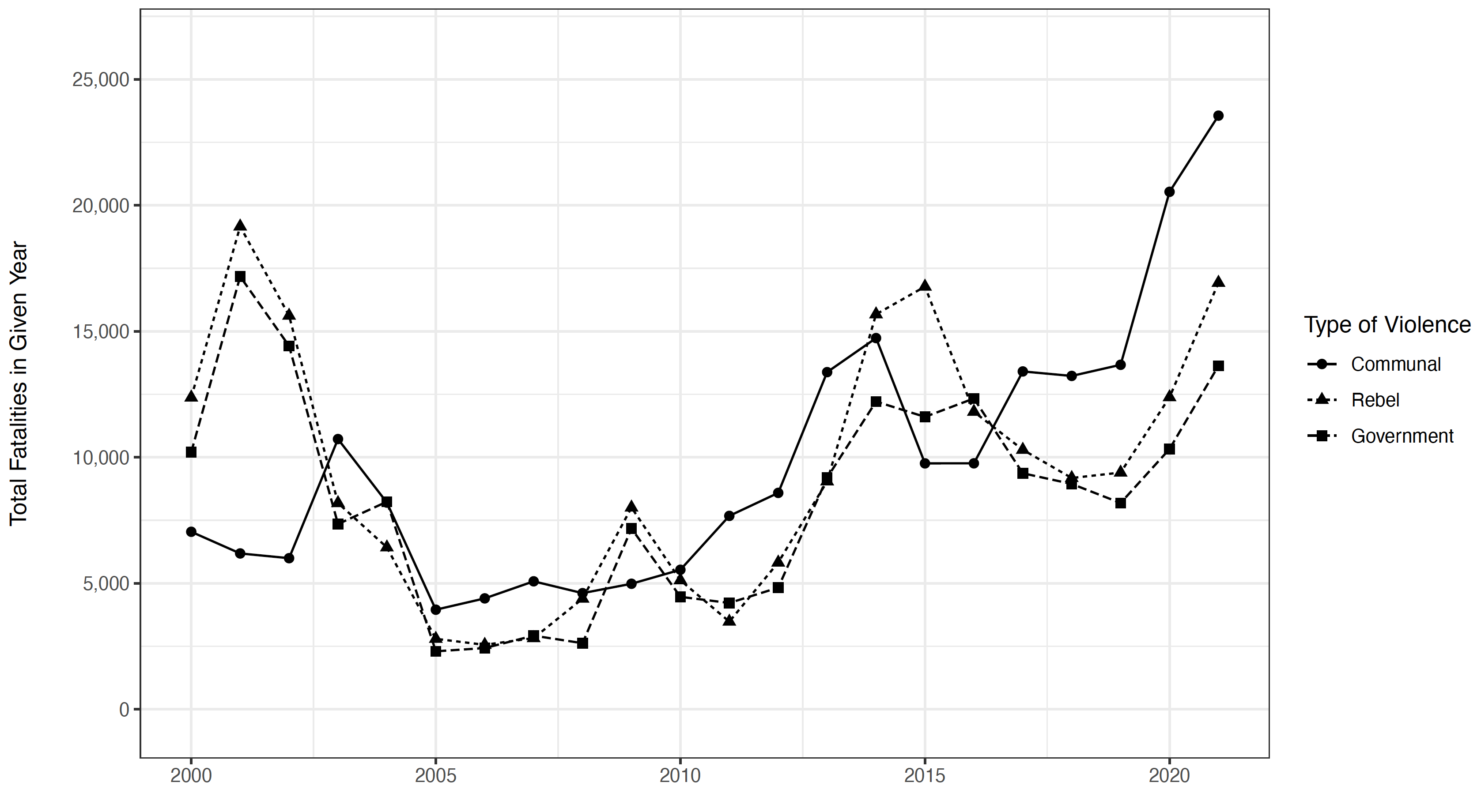

The clear upward trend in the number of fatalities caused by communal violence in the region indicates that the problem is getting worse (See figure 2)

In response, the international community is increasingly tasking UN peacekeepers with protecting civilians from communal violence. Though the UN has committed significant resources, whether peacekeepers succeed remains an open question. Indeed, any survey of places with local-level peacekeeping operations reveals at least some degree of communal instability. Although we should not necessarily blame the UN for all lingering tensions, this instability has rightfully called peacekeepers’ effectiveness into question. Given that climate change, global migration patterns, and the growth of violent extremism will likely exacerbate communal disputes in the coming years, it is vital to understand how UN peacekeepers can help resolve them.

Scholars typically argue that peacekeepers help armed group leaders make lasting agreements that stabilise conflict settings from the top down. But my research shows that UN peacekeepers succeed when local populations perceive them to be relatively impartial. Such peacekeepers convince all parties that they will punish those who escalate communal disputes regardless of their identity, which increases communities’ willingness to cooperate without the fear of violence.

In a recently published article, I test this argument with a lab-in-the-field experiment carried out in Mali, a West African country with ongoing communal conflicts managed by troops from the UN and France. The evidence shows that some, but not all, types of peacekeeping have a strong positive effect on the willingness to cooperate in a post-conflict setting. Whereas the UN treatment increased willingness to cooperate by 32.7 per cent relative to control, the France treatment had no substantive or statistically significant effect.

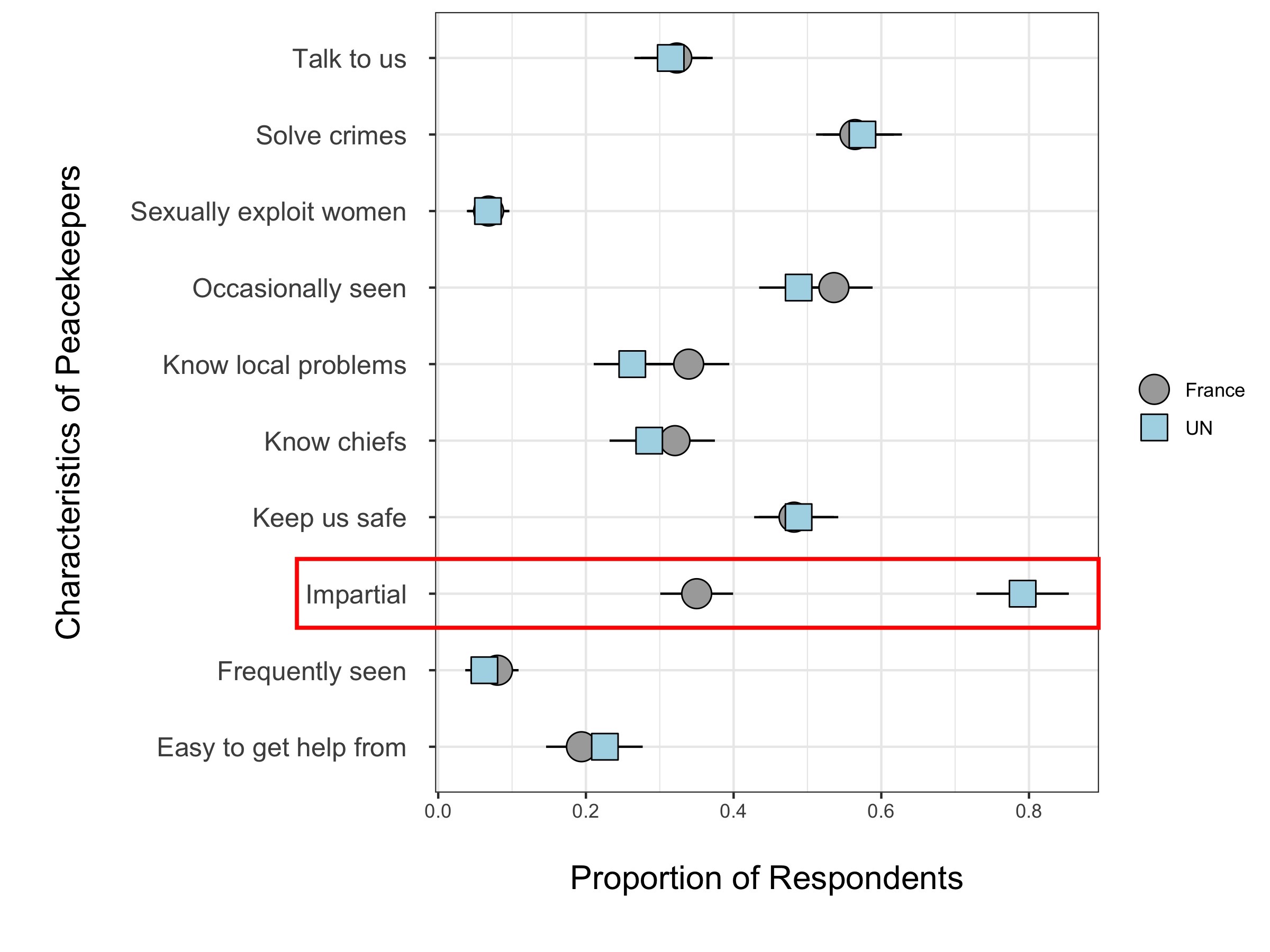

Perceptions of the UN as an impartial actor likely drive these divergent findings. In a follow-up study, I asked 874 Malians living in 20 rural and peri-urban areas a series of questions about the characteristics of UN peacekeepers and French soldiers. Whereas nearly 80 per cent of all respondents think of UN peacekeepers as impartial, fewer than 40 per cent say the same about French soldiers (see highlighted box in Figure 3).

This underscores the enduring importance of impartiality to the success of UN peacekeeping operations in sub-Saharan Africa. The challenging nature of recent deployments has caused some leaders to push peacekeeping operations toward counterinsurgency. This would be a mistake. Populations rapidly turn against counterinsurgents, which would endanger peacekeeping operations and the peacekeepers themselves.

Moreover, sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) by UN peacekeepers against local populations turns domestic groups against them, much like the use of force does. The importance of local perceptions to peacekeeping effectiveness suggests that SEA is not merely a normative concern for the UN.

Ultimately, local-level peacekeeping can lay the foundation for sustainable peace in war-torn states such as Mali. Yet, to foster long-term reconciliation, local societies must use the gains from UN-enforced cooperation to create domestic institutions and restore social trust to sustain peace even after the peacekeepers have gone.

Photo: UNAMID Peacekeepers Patrol in North Darfur. Credit: UN Photo/Olivier Chassot. Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0