Successive Nigerian governments have shown a strong drive to diversify the economy through specific sector policies, particularly import substitution. This has usually been triggered by foreign exchange crises. Poorva Karkare and Michael Odijie argue that Nigeria must move away from a one-size-fits-all protectionist trade policy, also known as backward integration, to increase technical capacity and ramp up the production of goods and services.

Under backward integration, the importation of a selected product is largely banned; importation licences are restricted to importers that can provide evidence of their production of a domestic replacement. Yet, over-reliance on trade restrictions by the government has taken attention away from implementing other relevant policies.

Our research contextualises Nigeria’s trade and industrial policies in two important sectors: rice and pharmaceuticals.

In 2017, Akinwumi Adesina, President of the African Development Bank, predicted that Nigeria’s Dangote would become the largest exporter of rice in the world by 2021. From 2010 to 2015, before being elected President of the Bank, Akinwumi Adesina served as Nigeria’s Agriculture Minister, helping to shape the country’s industrial policy on rice production. The success he predicted reflected his complete faith in this policy.

Under Nigeria’s policy on rice importation, licences and quotas were granted only to importers that invested in the production chain by building mills and large farms. This was a form of import substitution, wherein quotas effectively provided importers with rents that could be used to increase domestic production. However, there were numerous problems with the policy.

First, the ruling elites used the rents to distribute resources to their supporters. In some cases, the receivers of quotas had no connection at all with the rice sector.

Second, few performance monitoring mechanisms were in place to ensure receivers’ accountability for the support. Some traders, uninterested in rice farming, falsified evidence of domestic investment to obtain import quotas from the government. Based on this fabricated evidence, the Nigerian government continues to exaggerate the extent of domestic investment in rice production.

Third, small- and medium-scale rice farmers who were not traders initially felt cheated by the policy because they were not entitled to import quotas. However, in 2015, the Buhari administration broadened the policy to include credit, higher-quality seedlings, fertiliser, and irrigation. Nevertheless, there are concerns over the viability of these policies and programmes as farmers default on repayments- regarding credit as grants.

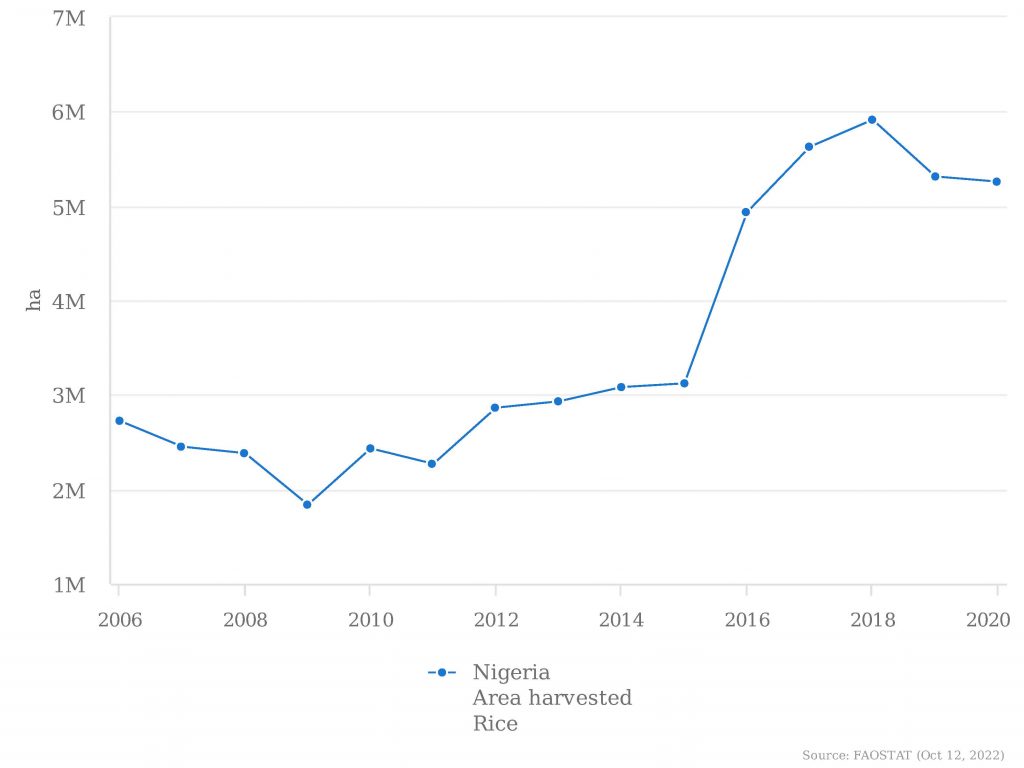

After 2015, these non-trade policies increased the scale of rice cultivation in Nigeria than the trade restrictions that had started years earlier. (Figure 1)

An important obstacle to developing the rice sector in Nigeria is the large-scale smuggling of imported rice from neighbouring countries, especially Benin. The extent of this smuggling increased astronomically with the consolidation of trade protection. It was in this context that the Nigerian government decided to close the country’s land borders.

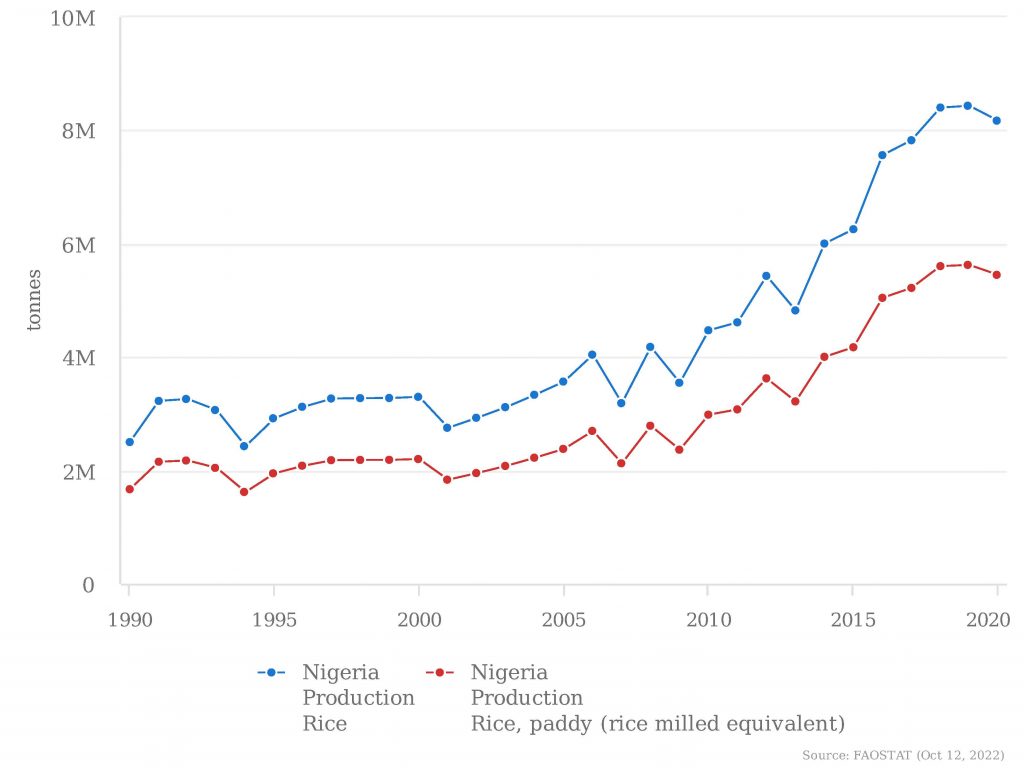

Although the border closure increased rents, as the price of rice almost doubled, it did not sustainably increase production. On the contrary, the quantity of milled rice decreased after the 2019 border closure. As the production graph below shows, the output of rice in 2020 was lower than in 2019.

Nigeria is still not self-sufficient in rice production; it continues to import about 2 million tonnes per year. Some of the current gaps in Nigeria’s rice production are created by non-trade issues like value chain-specific constraints beyond production. The 2019 land border closure slowed down the development of a regional production chain between Nigerian mills and paddy from neighbouring countries. Furthermore, the border closure created problems for other sectors that depended on border crossings. Although smuggling is a constraint on production, the government over-emphasised trade restrictions in response, with the assumption that it would automatically boost domestic production. This, however, was not the case.

In pharmaceuticals, trade policies are also the primary measure used by the Nigerian government to boost domestic production. In 2005, the government introduced a National Drug Policy that led to a ban on the importation of 17 commonly used drugs. Instead, local drug manufacturers were expected to meet about 70 per cent of Nigeria’s demand for medicines by 2008. The ban is still in place in 2022, and there has been no significant increase in drug production.

Nigeria’s pharmaceutical industry has not been able to build the technological capabilities needed to upgrade drug production. Complex drug manufacturing requires technological expertise that cannot be obtained by trade protection alone. The Nigerian government and its agencies, e.g., the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC) lacks the technical capacity required to identify gaps in production. This is coupled with the failure to upgrade production through appropriate technology transfer, ideally negotiated and monitored by the government and relevant agencies.

While drug production in Nigeria has remained largely insufficient to meet domestic needs, there is also limited focus on creating demand for these drugs by, for instance, strengthening the public procurement system and addressing inefficiencies therein. Without a solid foundation for boosting both demand and supply of pharmaceuticals, trade policies alone are unlikely to bring substantial development in this sector. However, the current administration has continued to introduce many other trade policies since 2016, such as an import adjustment tax on raw materials, reduction of duties on intermediate goods while increasing them on finished products where domestic production could replace importation and much more.

COVID-19 disruptions have further increased the need to promote domestic production to preserve drug security. This has led to the creation of a credit support scheme for drug manufacturers in the healthcare sector, including pharmaceuticals. While production has increased to some extent, there seems to be a mismatch between the policy and actual production problems.

Nigeria’s one-size-fits-all policy approach

The obvious problem with sector policies in Nigeria is that they tend to take a “one-size-fits-all” approach. Although rice and pharmaceuticals are different in almost all respects, especially in the nature of production constraints they face, the sector policies are similar.

A proper sector policy must first define the production constraints in each area and then create a set of strategies that match and can effectively address the constraints. For example, constraints on electricity, transportation, the supply of agrochemicals and fertilisers, as well as the adoption of modern varieties and security problems are key production problems in the rice value chain. While a regional production network could create opportunities to solve some of these problems, an emphasis on trade protection reduces the possibility of finding solutions. Drug production may require the kind of policy that would guarantee knowledge transfer from joint ventures with established producers, and a guaranteed market both at the national and regional level through harmonisation of standards.

While industrial policies are required to boost industrial production in Nigeria, they need a wider array of tools than simply import restrictions. These policies should fulfil a vital function of strategic coordination to address binding constraints in sector development.

Photo: Samuel Wölfl from Pexels