Based on his latest paper, Professor Teddy Brett draws on classical ‘dualist’ and ‘new institutionalist’ theories to explain the ongoing crises that devastate conflicted African states. He suggests alternative strategies exemplified in Uganda’s transition from colonialism to a military dictatorship and a relatively successful competitive autocracy.

Creating political authority in conflicted societies

Many conflicted societies have been devastated by violence and governed by rulers who treat democracy and open markets with contempt since the end of the colonial era. They pay lip service to the liberal democratic principles set out in the Sustainable Development Goals but have failed to build strong states that guarantee public authority. This is because they lack the necessary resources and depend on the military and illiberal traditional institutions and belief systems to stay in power. These failures have legitimated the claims of their critics, who reject the liberal democratic state-building project and call for a return to African values and institutions.

These setbacks can only be overcome by using classical dualist, new institutionalist and hybridity theories to resolve the contradiction between the work of the orthodox state-building theorists who have dominated policy agendas in post-colonial Africa, and their critics who have used its many failures to reject it altogether. They accept the need for strong liberal democratic states but recognise that all late developers have to overcome far greater challenges and adopt very different policies from mature democracies as they create them. They point out three theoretical issues that must be understood if these societies are to consolidate democratic transitions:

- Why building strong states and market economies is both necessary and heavily contested

- Why opposition political movements use democratic theories to justify their right to rule, but adopt authoritarian solutions when they take power; and

- Why traditional institutions continue to sustain political authority and livelihoods in marginalised societies without perpetuating authoritarianism, theocracy and patriarchy

Classical dualists, contemporary institutionalists, and hybridity theorists recognise that these countries do need to build strong democratic states but can only do so by managing the conflicts generated by the existence of modern and traditional elites, social classes, and cultural systems. They must also invest in the political, economic, and human capital needed to sustain their transitions to democratic statehood. This approach turns modernisation into a heavily contested and long-term process that began with the colonial intrusion that imposed modern authoritarian states, economies and civic institutions dominated by expatriates on pre-literate societies. This confined the local population to reconstituted traditional institutions, but also created new indigenous elites that eventually used liberal democratic principles to demand independence.

However, these emergent elites lacked the skills and resources needed to manage their formal states and economies that still depended on expatriates, and public authority was still dependent on illiberal traditional institutions that excluded most people from public politics. They had to assert their autonomy by taking up the bureaucracy, formal economy, and satisfying the demands of the newly enfranchised peasantry and petite bourgeoisie, which generated zero-sum conflicts that took more or less disruptive forms in different countries.

Tracking these processes by looking at Uganda’s modern history provides us with important insights that are applicable to many other conflicted states in Africa.

The creation, dissolution and reconstruction of the Ugandan State

Uganda experienced a relatively inclusive and peaceful colonial encounter but did so by limiting the destructive impact of the capitalist revolutions driven by settlers in Kenya. The country eventually produced a small middle class that has consistently attempted to implement democratic state-building projects that have been derailed by the class, ethnic and sectarian conflicts and structural weaknesses inherited from the pre-colonial and colonial periods. But these experiences also transformed the opportunities and threats confronting each new regime. Milton Obote’s UPC had to replace experienced expatriate officials and firms with inexperienced ones and resolve long-standing conflicts between the southern kingdoms and segmentary societies in the north. This led to the events of 1971-1980; a military coup, civil war, state failure, and economic collapse.

National elections were held in 1980, and UPC emerged victorious amidst suspicions of rigging. These complex events also created a new professional and capitalist class that led to the formation of the National Resistance Movement (NRM) led by Yoweri Museveni. The NRM was committed to democracy and economic reconstruction and began a civil war in 1981 that destabilised the economy and state capacity until 1986, when they came to power.

Rebuilding public authority in Uganda after 1986

The NRM depended on strong donor support and the new classes and organisational systems that had provided key services during the dark years. This enabled them to initiate a successful state-building and economic reform programme- but one that combined liberal and illiberal institutions in complex and often contradictory ways.

It restored public authority by managing a gradual transition to multi-party elections. It first incorporated leaders of the other parties and rebel groups that gave up their arms, into a ‘broad-based’ government. It set up new local councils in 1987, allowed traditional rulers to return, but curtailed their authority and divided their Kingdoms into multiple districts. It set up an indirectly elected Parliament in 1989, allowed existing political parties and a critical media to operate legally, but postponed multi-party elections. It organised ‘no-party’ national elections in 1996 and multi-party elections in 2005 that the NRM has won ever since.

The NRM restored peace by de-politicising and ‘de-ethnicising’ the new national army by incorporating soldiers and officers from the defeated groups but kept NRM loyalists in top leadership positions. It initially attempted to suppress resistance movements in the north, but later negotiated peace agreements with key armed groups by granting amnesties to encourage rebels to leave the bush. Former rebel leaders were also allowed to take leading positions in new Local Councils. The regime initiated a large donor-funded Reconstruction Programme to rebuild the northern economy.

The NRM’s initial attempt to resurrect the ‘left-wing’ state-led economic structures that had dominated policy agendas in the past was required by the donors and supported by a liberal faction in the Party who were keen to make a radical shift to market-based delivery systems. NRM privatised bankrupt state-owned enterprises, and sub-contracted public services to private firms, NGOs, local councils, and traditional institutions. It was unable to finance state services or local councils, but elections legitimated the authority of local elites who also used hybrid solutions to deliver services in both regressive and progressive ways, like punitive witch-cleansing exercises in some areas, and the authority of churches and clans to deliver key local services in others.

The movement encouraged foreign investment, protected property rights, removed currency controls, imposed fiscal discipline, reduced inflation, and strengthened its regulatory role, supported by donors who covered 50 per cent of the recurrent and 80 per cent of the development budget during the early years. These early reforms partially decriminalised the state and liberated the emergent African capitalist class from the constraints imposed on it by earlier statist and predatory regimes. They produced a rapid return to growth and significant increases in GDP and access to education.

The regime and donors then made a formal shift from a neo-liberal to a poverty-alleviation strategy in the late 1990s, which ended the donor-dependent and interventionist industrial policy strategy.

These successes turned Uganda into the ‘rising star’ of the donor community by the start of the 2000s, but they depended on hybrid rather than orthodox liberal or neo-liberal solutions, so they have yet to guarantee a sustained and equitable transition to a modern agrarian and industrial economy or open social order.

Rapid population growth has undermined attempts to improve access to education, social services and jobs; agriculture is still dominated by small-scale farmers using rudimentary technology; conflicts between peasant and capitalist farmers over land are generating serious conflicts. Local industries are undermined by imports, while the dynamic but fragmented national capitalist class still depends on political rents and favours that encourage corruption and non-coherence in policy implementation.

These problems have been compounded by the regime’s failure to carry through its earlier commitment to bureaucratic reform and good governance once it had consolidated its authority and was no longer subject to donor supervision. It had strengthened the state to guarantee property rights and provide key public services by the late 1990s. However, the introduction of competitive multi-party elections has forced the NRM to use state power to retain control. Therefore, ‘personalisation, patronage and coercion’ have returned, turning it into a ‘competitive autocracy’ rather than a liberal democracy. These strategies have intensified opposition and undermined the NRM’s foreign reputation.

The NRM has therefore managed a major political, economic, and social transformation but one that does not conform to orthodox policy prescriptions and could easily be derailed unless it continues finding ways to reconcile the demands of its emergent modern and its traditional elites and social classes.

I have, therefore, questioned the optimism of those who believe that democratisation and liberalisation can generate an immediate and stable transition to modernity in conflicted states, and the pessimism of those who believe that these states can never overcome the structural weaknesses and zero-sum conflicts that still block their attempts to do so. Progressive African elites do recognise the need for strong democratic states and market economies, but they do need to limit people’s expectations and rely on illiberal traditional institutions while they invest in the capacities they need to create open social orders. They can only do this by creating inclusive political settlements that incorporate formerly excluded social groups into public politics as they strengthen the political, economic, and civic organisations needed to manage open social orders that depend on negotiated and binding agreements rather than violence.

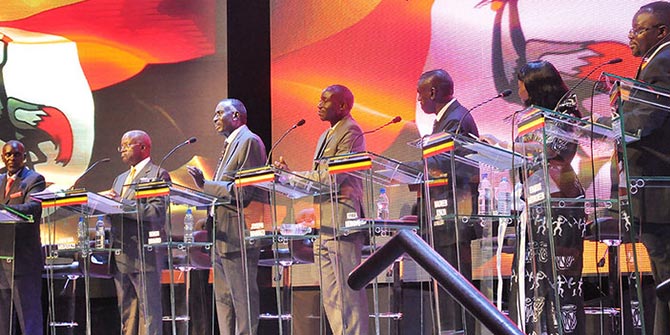

Photo: President Yoweri Kaguta Museveni. Credit: PPU-UGANDA/Jacob Kato