Unplanned or forced migration in response to climate change can expose people to new risks and vulnerabilities. But informed migration in full knowledge of climate risks can, when well supported by local, national, and regional policies, help reduce vulnerability, build resilience, and prevent future loss and damage, argue Nick Simpson and Sarah Rosengaertner.

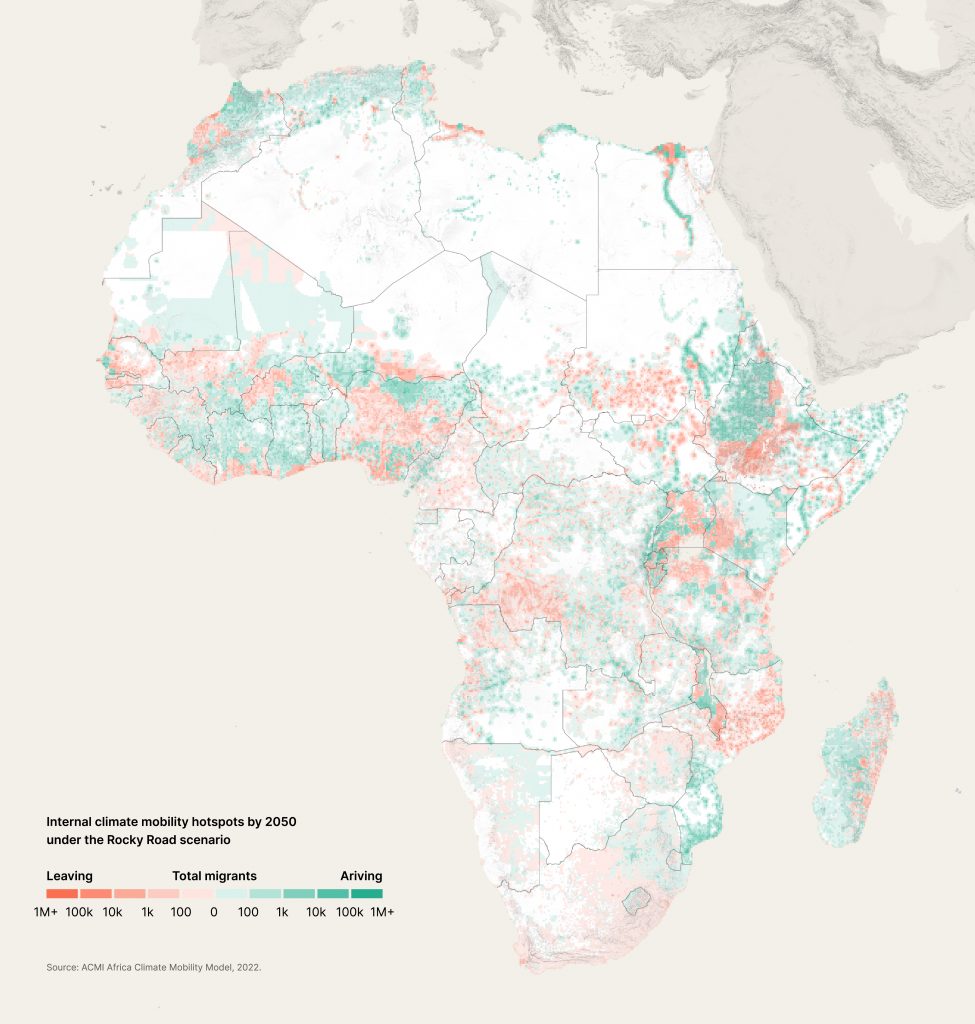

Future projections of climate mobility

By 2050, climate change is projected to cause 1.2 million people to move across national borders within the African continent. This would account for 10 per cent of all cross-border migration but is only a small fraction of the expected climate migration in Africa. Up to 5 per cent of Africa’s population – potentially 113 million people – could be on the move within their home countries due to climate impacts in the next thirty years.

Pasturelands, rainfed agricultural lands, coastal areas, borderlands, and cities are all likely to witness increased migration as climate risks intensify. African pastoral areas are projected to lose up to 4 million people by 2050 due to the increasing frequency and duration of droughts. Coastal areas could lose up to 2.5 million people because of sea level rise and, despite projected rapid urbanisation, climate impacts could force up to 4.2 million people out of urban areas by the middle of the century. There is, however, great variability across cities: while some are forecast to remain destinations regardless of climate risks, others could see movement out of risky areas, such as oceanfront or riverside settlements.

Realities of climate mobility

The findings of the African Shifts report indicate a strong preference among Africans to stay where they live. Despite the increasing prevalence of climate-related stressors, such as extreme heat, water scarcity, and flooding impacting people’s health and livelihoods, many have a positive outlook for their futures. Most people have not even considered moving.

People have a strong attachment to place and community, especially when their livelihoods are tied to the local ecosystems, such as through farming or fishing. Beyond these attachments, aspirations are influenced by people’s self-assessment of their ability to move. Gender and age play an important role in shaping these aspirations, with young men most likely and older women least likely to move. Poorer, less connected, and less educated community members are also more likely to stay behind.

Climate change literacy rates – which is a measure of people’s understanding of the causes and consequences of climate change – are low and unequally distributed within countries and across the continent. This lack of climate literacy suggests that many people are deciding to stay or move without adequate information about the climate-related risks of remaining in place or those associated with relocation. As a result, their decisions are more likely to be reactionary rather than anticipatory, leaving people at higher risk of becoming displaced when disaster hits or stranded in place due to the erosion of their assets long after the opportune time to leave has passed.

The opportunities of climate mobility

People-positive adaptation efforts could build resilience and agency in the face of these climate impacts. If properly managed, it could enable some people to stay where they are rooted, help those who aspire to move to do so in a safe and informed manner, support communities that receive migrants, and anticipate and plan for situations where whole communities may need to relocate.

Recognising and supporting mobility as a legitimate coping and adaptation strategy can reduce the risks for those who move and allow communities to remain rooted in place. In the context of slow-onset climate impacts, it is rarely whole households or communities who relocate. Instead, some members leave to pursue opportunities and often support those staying behind. The resulting networks can strengthen resilience at a household and community level by diversifying revenue and support structures.

To improve the positive outcomes of climate mobility, training should be offered to young people, who are typically the first to move, to give them the green skills needed to make a positive contribution to their new locations. This could include the installation of solar panels for irrigation or market gardening. Improvements to women’s access to property rights, finance, and climate literacy will also increase their agency giving women the ability to move when they choose, not only when they are forced to.

Policy and planning

Towns and cities that will become hubs for climate migration will need data, resources, and the capacity to expand and target housing, transportation, and public services to those most in need. Without such investments and planning, cities risk becoming hotbeds of climate vulnerability. Rapidly urbanising areas, especially informal settlements, are particularly susceptible to increases in extreme heat, flooding, extreme rainfall, sea level rise, and coastal erosion. By anticipating and planning for climate risk and increased mobility, cities can take account of population shifts in their infrastructure planning, informal settlement upgrading and the provision of social services.

As climate mobility on the continent will be predominantly internal, national adaptation and development actions will be at the forefront of supporting affected communities and the people who move. African governments are developing ambitious adaptation policies that enable an environment for investment in the jobs and skills necessary to support resilience and a just transition. Laws and policies on migration, refugees, and displacement will have to adapt to the new reality to facilitate the movement of people across borders and ensure the protection of those who are forcibly displaced due to climate shocks.

There has already been some progress on this front. Member states of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) are leading the way by ratifying the Protocol on Free Movement in the IGAD region, which provides for the entry of persons ‘in anticipation of, during or in the aftermath of disaster’ (Article 16). These mutually beneficial provisions could inform ongoing discussions within other regional economic communities on ways to protect their citizens amidst the developing climate crisis.

Next steps

At COP27 in Sharm El-Sheikh, the Presidents of Botswana, Niger, Somalia, and Uganda committed to be Climate Mobility Champions. This adds to the political momentum for advancing a common policy agenda on this issue. Climate mobility can be an opportunity to further the integration and collective resilience of the continent, but only if action is taken soon.

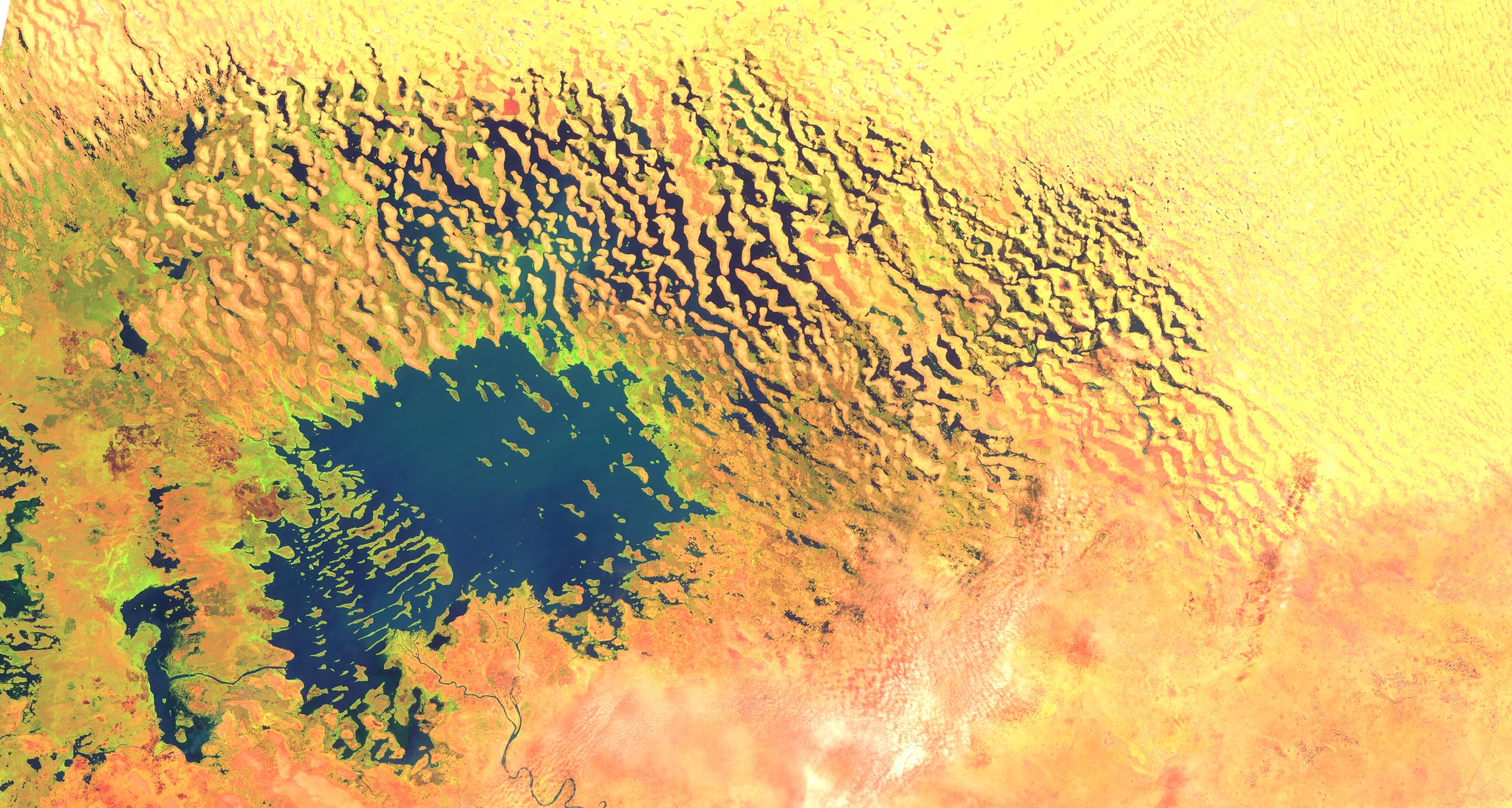

Photo credit: EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid used with permission CC BY-NC-ND 2.0