The “security turn” in China-Africa relations is not a return of the brutal colonial history with a dragon face. Rather, non-interference still is, and will likely remain, the guiding principle of China’s security engagement with Africa, writes Mamoudou Gazibo and Abdou Rahim Lema.

China’s efforts to deepen its relations with African countries have raised uncomfortable questions regarding its long-held foreign policy doctrine of non-interference. The debate is becoming even more intense because of Beijing’s expanding engagement with African countries in the area of peace and security. China is consolidating its involvement in multilateral peacekeeping and peacebuilding missions in the continent while also increasingly trying to institutionalise its security presence there. In 2012, the China-Africa Cooperative Partnership for Peace and Security was established to mark a turning point in the China-Africa relationship as discussions on peace and security in Africa became more prominent. Thanks to the Cooperative Partnership, the two parties have held regular China-Africa forums on peace and security, train and exchange more security personnel, and even cooperate with police and law enforcement.

Most discussions on the subject suggest that China is doing away with its foreign policy principle of non-interference. But China’s policy has been more consistent than what most observers would like to believe. Though China’s entrenched presence in Africa is increasingly forcing it to deal with various African crises, Beijing has so far been able to do so in a more pragmatically adaptive manner than it is credited for. The adaptive pragmatism has allowed the Middle Kingdom to get involved in Africa’s peace and security landscape without overtly compromising its traditional posture on non-interference.

Is non-interference non-intervention?

Discussions on the issue have mostly been misled by the failure to make a crucial distinction between the Chinese terms for non-interference (不干涉原则, Bù gānshè yuánzé) and non-intervention (不干预, Bù gānyù). The former puts a particular emphasis on “干涉, gānshè” (interference), which has clearer imperialist and hegemonic connotations, while the latter can, depending on the circumstances, be neutral, positive, or negative. That distinction is important for both African countries and China. Major international declarations by the two parties (e.g., FOCAC Declarations and Action Plans) carry similar messages of opposing the willingness of powerful states to use covert and/or overt force to achieve their foreign policy goals. This reflects a shared history with African countries of colonial exploitation and foreign interference in their internal affairs. African countries understand that distinction too well. According to Article 4 of the Constitutive Act of African Union (AU), for instance, “interference by any Member State in the internal affairs of another” is strictly prohibited; but the AU has “the right…to intervene in a Member State” in case “of grave circumstances, namely: war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity.”

History Matters…

To better understand China’s foreign policy principle of non-interference, one also needs to consider the historical context in which the country initiated its “Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence”—namely, mutual respect of territorial integrity and sovereignty, mutual non-aggression, mutual non-interference in internal affairs of each other, equality and cooperation, and peaceful co-existence. The decades-old foreign policy of non-interference in the internal affairs of other countries was forged in the early days of the People’s Republic of China under the rule of the Communist Party and has since been playing a defensive role against foreign meddling in its internal affairs. The policy was set to guard against the attempts by external powers to dictate or impose policies on Chine through economic policies or by directly or indirectly participating in regime change, coups d’état and deployment of mercenaries against the Communist Party.

…And Consent Matters, Too

Non-interference plays a double role. In addition to the defensive role the policy plays, China also uses it as a strategic tool in its engagement with Africa (and the broader Global South). In practice, this means that Beijing seeks the prior consent of African governments before it gets involved in their domestic affairs.

That strategy has allowed Beijing to seek solidarity with African (and other developing) countries while at the same time distancing itself from what it usually considers “hegemonic” policies of the Western powers. In that sense, non-interference foreign policy allows Beijing to present itself to African and other developing countries as a benevolent alternative to traditional powers.

The launch of Xi Jinping’s “Global Security Initiative” (GSI) attests to that effort to effectively paint China as an alternative power in global affairs. The GSI followed the usual tradition of being heavy on rhetoric but light on substance, but the recent publication of “The Global Security Initiative Concept Paper” provides additional details about the initiative. Clearly, very little about it is really “new”; it is mostly the aforementioned Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence wrapped in new cloth. It restates, for example, the long-standing Chinese foreign policy guiding principles on state sovereignty, non-interference in the internal affairs of other countries, multilateralism, dialogue, peaceful coexistence, etc. But the GSI reflects Beijing’s growing ability and readiness to create alternative institutional settings to discuss and shape international security in Africa and far beyond.

Take away

The “security turn” in China-Africa relations is far from being a return of colonial power structures. China cares about how its African partners perceive it and tries to position itself as a better listener than the Western powers. The form of engagement between the two parties is influenced by the reality on the African ground that pushes China to be adaptable in dealing with the challenging security and political environment in the continent without compromising its traditional posture on non-interference. This adaptive pragmatism is likely to continue to shape China’s engagement in Africa for the foreseeable future.

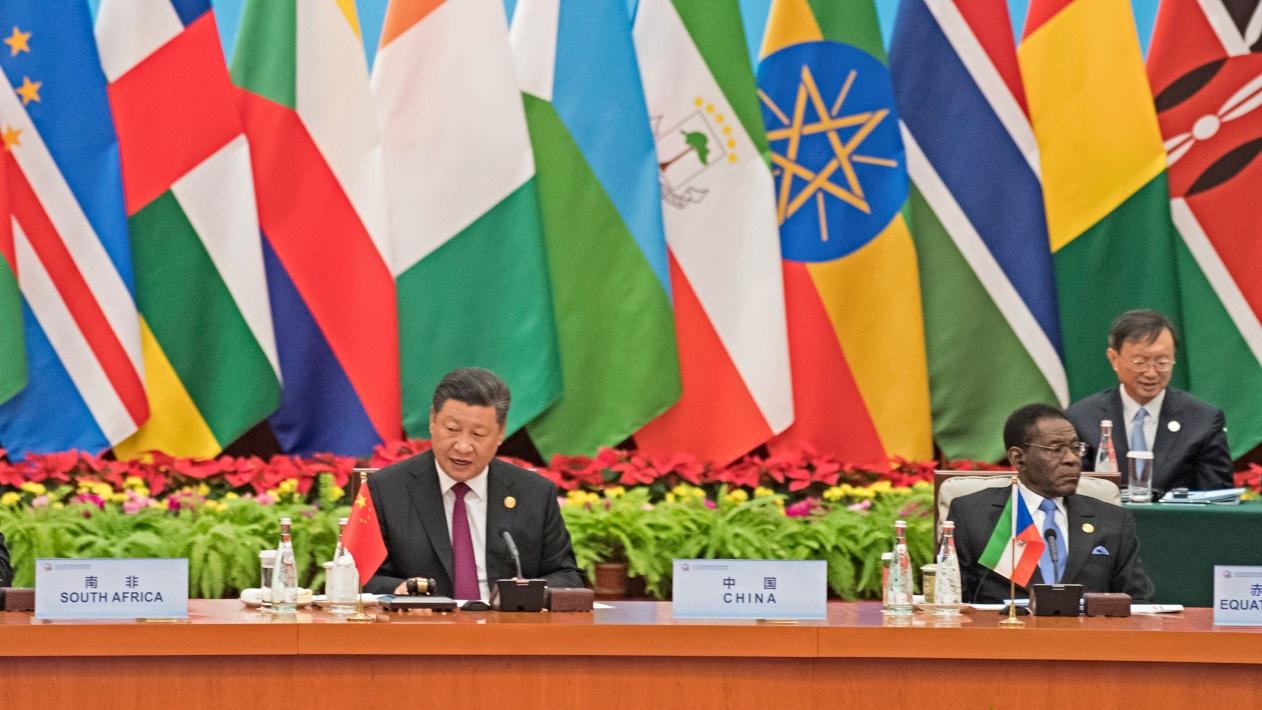

Photo credit: GovernmentZA used with permission CC BY-ND 2.0