Europe is placing insurmountable barriers in front of Africans trying to get visas to visit. This policy is denying people opportunities and doing Europe more harm than good writes Marta Foresti and Otho Mantegazza.

The 2023 Architecture Biennale opened in Venice in May. The 18th edition of one of the most significant international cultural events is curated by Scottish-Ghanaian architect Lesley Lokko and titled Laboratory of the Future. The Biennale’s website quotes Lokko saying: “For the first time ever, the spotlight has fallen on Africa and the African Diaspora, that fluid and enmeshed culture of people of African descent that now straddles the globe”

Despite working on one of the most prestigious exhibitions in the world, some of Lokko’s collaborators were denied visas to travel to Venice. Ironically, paradoxically, and tragically because they are African. Specifically, African ‘young men’. The paperwork from the Italian Embassy in Accra states that there were reasonable doubts on their ‘intention to leave the territory, or state, before the expiry of [their] visa’. In other words, they cannot be trusted to come on a work trip in case they tried to stay in Europe illegally.

This is just one story. There are numerous examples of people who have struggled to get a visa for a work meeting, artists who cannot make it to festivals, journalists who cannot report from certain countries, colleagues who are banned from some countries because of existing visas on their passports, or people who marry a ‘third country national’ and cannot live or go on holiday together.

Visas regimes are not equal or reciprocal. An Italian national can obtain a visa to Sierra Leone on arrival for £30. A Sierra Leonean wishing to travel to Italy for a business meeting must undertake two separate trips to the Italian Consulate in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire, over several weeks at eye-watering costs.

Going places for short visits, temporary work, or study is often vital for business and personal development. Visa regimes are vital components of trade agreements and critical in some key sectors of modern economies, from culture and the arts and tourism to tertiary education and research. Yet it is becoming harder for Africans to get visas. Wait times to obtain a short-term visa to the US have exploded. The research project Visa Limbo estimates that the average wait for a visitor just to get an interview appointment for a visa is 111 days. That jumps to 458 days in Nigeria, 425 in Uganda and 370 in Benin.

Getting to Europe

Things are not much better in Europe. Schengen countries, that make up the EU’s ‘passport-free zone’, have agreed on a common short-stay visa regime. This allows third-country nationals to travel to any member of the Schengen Area for up to 90 days for tourism or business purposes. This provides a common standard to the application process as well as precious data to better understand what happens to visa applications.

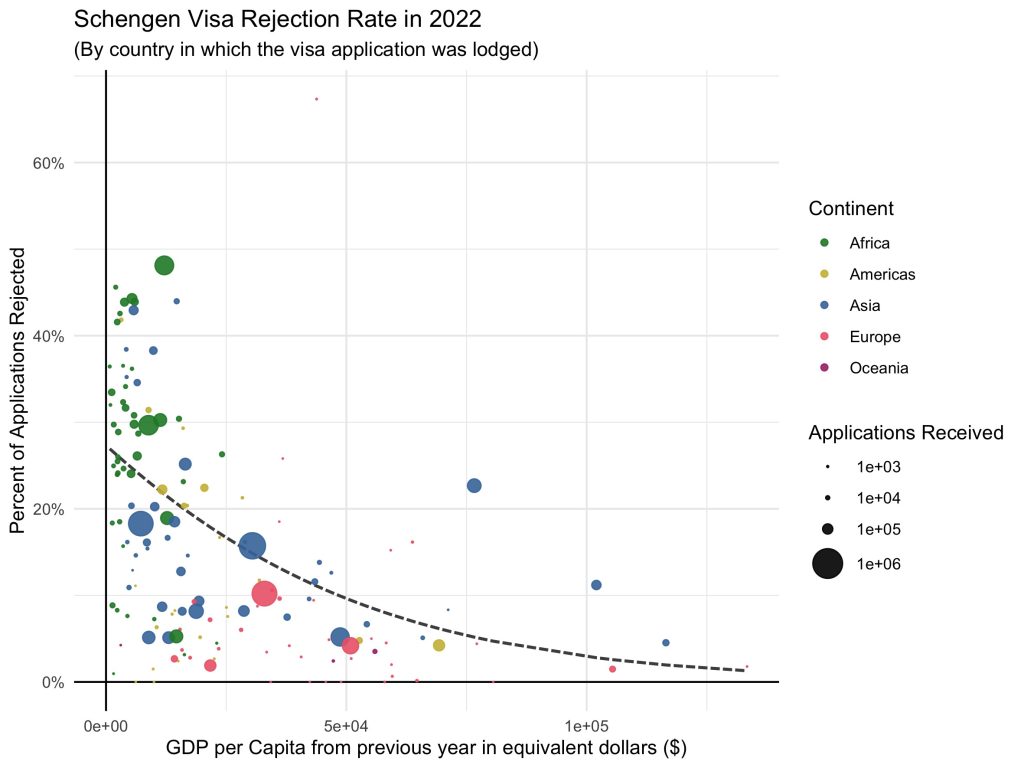

Initial analysis suggests that the success rate of a Schengen visa application depends on the GDP per capita of the country where the application is lodged. The poorer the country, the higher the rejection rate.

The Schengen visa rejection rate is especially high for African countries. While this may not come as a surprise in the context of ongoing tensions between Africa and Europe on migration matters, it points to a fundamental failure of a system designed to be reciprocal and to facilitate, not hinder short-term and temporary visits.

European countries want African counterparts to ‘take back’ their ‘illegal migrants’ that have entered Europe. Yet the return rates are low. Senegal for example only accepted 9 per cent of returns orders between 2015 and 2019. Unsurprising given that, more than 40 per cent of Schengen visa applications lodged in Senegal are rejected. It takes two to tango, as they say. If we are committed to better and more equal relations between Africa and Europe, visa regimes need fixing.

Europe is rapidly ageing, and its labour gaps are widening in critical sectors of the economy, not least in the health and care sectors. Governments are working hard to address this problem but are focused on doing so ‘domestically’. This has resulted in policies such as the return to nativism in Italy and the highly problematic Illegal Immigration Bill in the UK. Europe cannot afford this ‘hardcore’ visa game with African countries; it is not in its long-term interest. When it comes to labour, trade, and skills Europe needs Africa more than Africa needs Europe. With aid increasingly less relevant to many African economies, Europe has only a few comparative advantages to what China and increasingly Russia have to offer. But it could put on the table greater access to business visas.

This prominence of international migration on the political agenda in Europe has created an environment that makes it much harder for people to visit for work or leisure, at the cost of collective opportunities.

Visa friendly zones

There is relatively little research and evidence on the true financial and opportunity costs of visas and the functioning of different visa regimes around the world.

They are, however, a political choice. Visa-free zones exist and function well, as Schengen demonstrates. Plans are in place to facilitate visa-free travel across Africa and the Africa Development Bank estimates that two-thirds of African countries have adopted more liberal visa policies since 2016. Other regional agreements are in place in Latin America and beyond.

By the time of the next Venice Architecture Biennale in 2025, it should be possible that all those involved will be able to visit, no matter where they are from.

Photo credit: Global Panorama used with permission CC BY-SA 2.0

I could not agree more . It is interesting that Global North countries are negotiation all things except visa policies with the global south countries.

I totally agree with you. It is so pathetic to know among African countries we still need visas to visit each other for business and education purpose, but then some European citizens can just fly in with minimal/without restrictions across the continent. The restrictions are devastating in acquiring a Visa to Europe, even at the times were preaching of globalisation.