Despite the potential for a more pro-European electorate, attitudes to the EU have been subsumed into the Catholic-Protestant divide like most other political divisions in the province, argues James Dennison. Whereas pro-Europeanism can be predicted in Great Britain by age, wealth and education, in Northern Ireland religious identification is the only statistically significant predictor of voting to leave or remain. This evidence adds weight to increased academic consensus in recent years that attitudes to the EU are formed along identity lines, rather than economic interest.

Despite the potential for a more pro-European electorate, attitudes to the EU have been subsumed into the Catholic-Protestant divide like most other political divisions in the province, argues James Dennison. Whereas pro-Europeanism can be predicted in Great Britain by age, wealth and education, in Northern Ireland religious identification is the only statistically significant predictor of voting to leave or remain. This evidence adds weight to increased academic consensus in recent years that attitudes to the EU are formed along identity lines, rather than economic interest.

One of the least explored yet potentially more consequential aspects of the UK’s upcoming referendum on European Union membership is the prospective result in Northern Ireland. Most attempts to gauge the likely result of the referendum overall, such as ongoing polling by YouGov, survey only residents of Great Britain, leaving us relatively in the dark when it comes to Northern Irish attitudes to the vote. Moreover, there are intuitively two partially conflicting hypotheses about how residents of Northern Ireland will vote in the contest, each supporting conflicting theories about how attitudes to the EU are formed across Europe.

On the one hand, we might expect the Northern Irish to be considerably more pro-European than their compatriots in Great Britain. First, as the only part of the United Kingdom to share a land border with another EU member state, the often cited positive effect of British geographical isolation on Euroscepticism should not apply to the province. Second, the EU has arguably played a substantial role in diminishing sectarian conflict in Northern Ireland via a ‘considerable raft’ of spending under successive programmes and its institutionalised role in the Good Friday Agreement. Third, the considerable cross-border interaction with the far more pro-European Republic of Ireland as well as the four in ten residents who identify with Catholicism, which has been argued to have a positive effect on sympathy to European integration in Europe generally, both have the potential to make the Northern Irish Britain’s Good Europeans.

On the other hand, we might expect the cleavage in attitudes to Europe to be subsumed into the primary dimension of political conflict in Northern Ireland – the nationalist-unionist spectrum closely aligning to the two major religious communities. In this case, there would be a relatively even split between Catholic, nationalist ‘remain’ and Protestant, unionist ‘leave’ voters. This seems plausible on both sides of the spectrum. Amongst unionists, over the last twenty years the centre-right Ulster Unionist Party have lost ground to the more explicitly Eurosceptic Democratic Unionist Party, whose previous leader denounced the EU as a ‘Catholic Club’. The largest nationalist party, Sinn Féin, has moved from advocating, successively over the last fifteen years, withdrawal from the European Union before 1998, to ‘critical engagement’, to the adoption of the single currency in Northern Ireland, to its current policy of a United Ireland in Europe. There is therefore reason to believe that the EU referendum in Northern Ireland could be a sectarian vote along the lines of other elections in the province – producing a similar result in percentage terms to the rest of the UK. I use data from the 2015 Northern Ireland General Election Survey and the 2015 British Election Study to consider these possibilities.

On the other hand, we might expect the cleavage in attitudes to Europe to be subsumed into the primary dimension of political conflict in Northern Ireland – the nationalist-unionist spectrum closely aligning to the two major religious communities. In this case, there would be a relatively even split between Catholic, nationalist ‘remain’ and Protestant, unionist ‘leave’ voters. This seems plausible on both sides of the spectrum. Amongst unionists, over the last twenty years the centre-right Ulster Unionist Party have lost ground to the more explicitly Eurosceptic Democratic Unionist Party, whose previous leader denounced the EU as a ‘Catholic Club’. The largest nationalist party, Sinn Féin, has moved from advocating, successively over the last fifteen years, withdrawal from the European Union before 1998, to ‘critical engagement’, to the adoption of the single currency in Northern Ireland, to its current policy of a United Ireland in Europe. There is therefore reason to believe that the EU referendum in Northern Ireland could be a sectarian vote along the lines of other elections in the province – producing a similar result in percentage terms to the rest of the UK. I use data from the 2015 Northern Ireland General Election Survey and the 2015 British Election Study to consider these possibilities.

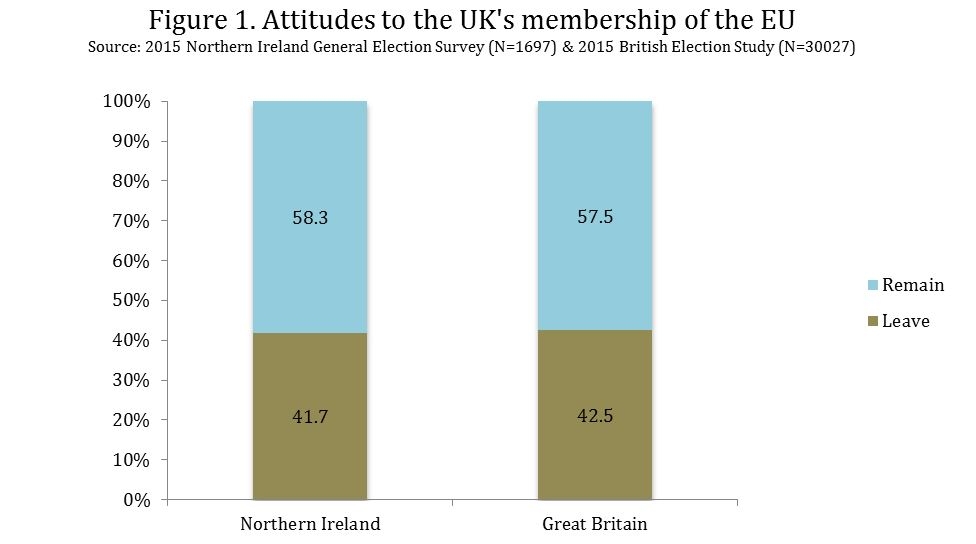

First, how does Northern Ireland compare to Great Britain? When excluding those voters who say they will not vote or don’t know how they will vote, we can see in Figure 1 that there is no major difference in prospective voting between Northern Ireland and Great Britain. However, it is worth noting that ‘Don’t Knows’ made up 25% of those surveyed in Northern Ireland, compared to just 16.4% in Great Britain, suggesting that the population of Northern Ireland – though split similarly to GB at the time of the election – is far more undecided. Regardless, the idea that a European land border, high EU spending and a different socio-demographic makeup has made Northern Ireland significantly more pro-European than the rest of the UK is discredited by these two data sets. [i]

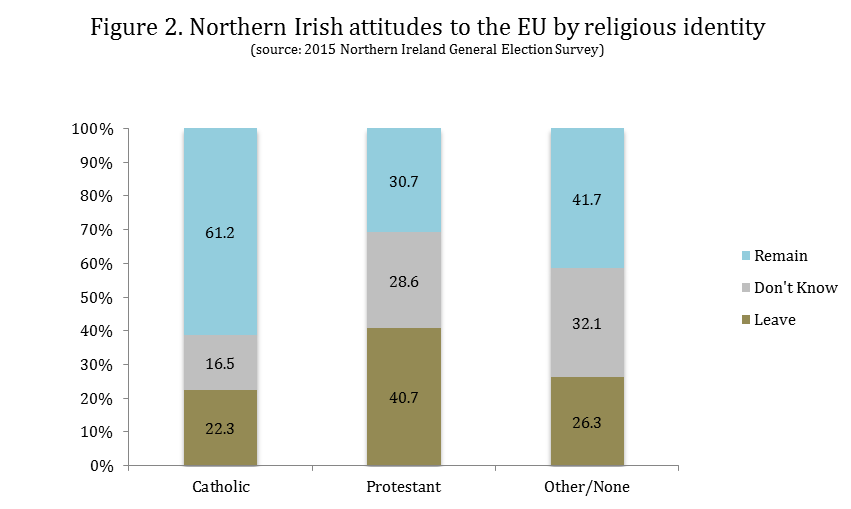

How much of the divide on Europe in Northern Ireland can be explained by religious loyalties? These survey results would suggest a lot. Nearly three times as many Catholics prefer that the UK stay in the EU rather than exit it, whereas Protestants, who are more divided on the issue, prefer that Britain leave at a ratio of 4:3. The 20% of the population who identify neither as Protestant nor Catholic are somewhere in the middle with 42% in favour of staying in and 26% in favour of leaving. It appears that a majority of one of the sides of the sectarian divide will be disappointed by the referendum result.

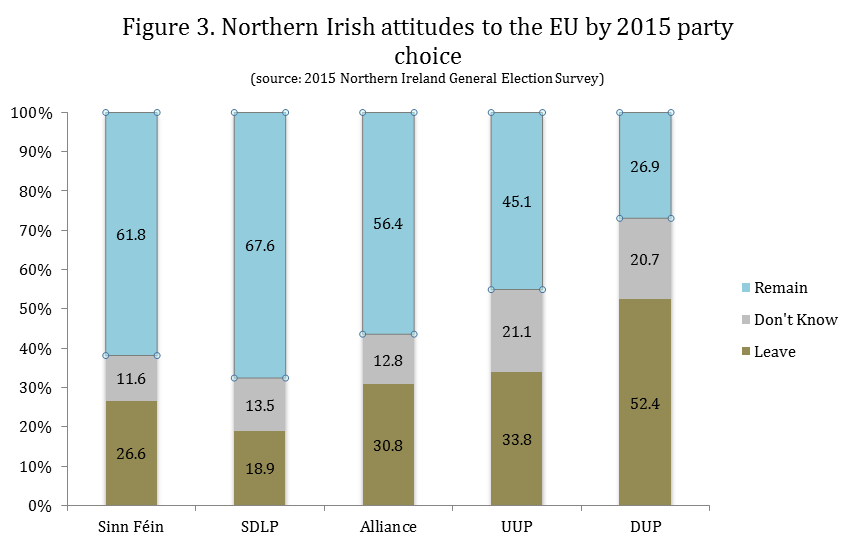

The communal divide on Europe follows that of Northern Irish party politics generally, though not in the simple linear terms one might expect. As shown in Figure 3, two things stand out. First, more voters of the centre-right Ulster Unionist Party prefer to remain in the European Union than to leave it – only DUP voters are in the main Eurosceptic. Second, as is often the case in European politics, voters of the more moderate nationalist party, the SDLP, are more pro-European than the hard-left Sinn Féin.

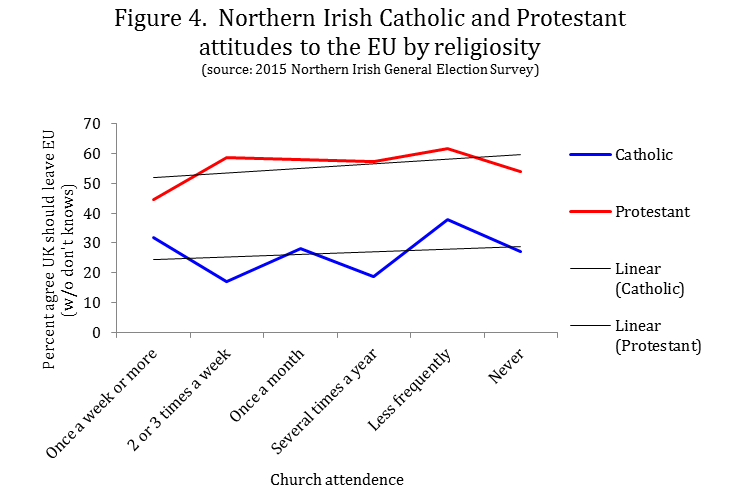

Similarly, if there were a simple linear relationship between religious denomination and attitudes to Europe then we might expect that greater religiosity would increase the effect of one’s religion on their attitude to the EU, i.e. the more religious a Protestant is, the more Eurosceptic they are, with the reverse for Catholics. However, as shown in Figure 4, there seems to be the same fairly weak relationship for both groups, with greater church-going associated with more positive attitudes to the EU. It would seem that though religious denomination in Northern Ireland affects attitudes to Europe it does so not via actual religiosity – Protestants who go to church more are actually less Eurosceptic – but via some other causal mechanism, perhaps along self-identity terms.

How do the effects of these specifically Northern Irish factors of religious communal identity hold up once split along the lines of the classic determinants of attitudes to the EU? Repeatedly across EU member states, but particularly in Great Britain, pro-Europeans have been shown to be younger, wealthier and more educated. Various academics have theorised that these factors either produce a more globalisation-friendly identity, making the individual favour European integration for reasons of self-image, or that they put the individual in a superior position to compete in the European labour market, making them favour the EU’s goal of dismantling of national economic protections. Regardless, we should expect age, income and education to strongly affect attitudes to the EU in Northern Ireland. Amazingly, as shown in Figure 5, the effects of these three variables are fairly inconsequential when compared to religious identification. Indeed, majorities of young, rich, well-educated Protestants are anti-EU, while older, poorer Catholics without university degrees remain pro-EU.

Indeed, when variables indicating religious denomination, religiosity, age, income and education are used in a multinomial logit model[ii], the only statistically significant predictor on voting to leave or remain is religious denomination.[iii][iv]

Overall, the best determinant of voting in the EU referendum in Northern Ireland will be one’s religious community. These results may matter because, though Northern Ireland makes up just 3% of the UK’s electorate, polls increasingly indicate that the result will be close and, judging by European elections, turnout is likely to be higher in Northern Ireland than in Great Britain. Furthermore, if the UK were to vote to leave the EU, the ramifications, in terms of cross-border activity, European funding and social stability, are likely to be felt hardest on that side of the Irish Sea. The religious community divide in Northern Ireland adds weight to increased academic consensus in recent years that attitudes to the EU are formed along identity, rather than economic interest, cleavages. However, these identity cleavages are weakly predictable, if at all, by the variables of age, education and income, which tend to be strong predictors of EU attitudes in other member states. It would seem that, despite having some of the fundamentals to be a country of Good Europeans, sectarianism is as primary to attitudes to the EU as it is to every other political cleavage in the province. The EU referendum is likely, therefore, to leave one side of Northern Ireland’s religious divide disappointed.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of BrexitVote, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image: Copyright Suzanne Mischyshyn and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

Shortened URL for this post: http://wp.me/p6zUkq-5D

_________________________________

About the author:

James Dennison – EUI

James Dennison is a PhD candidate at the European University Institute, Florence. His research interests include political participation, European politics and longitudinal methods. He is currently a Research Assistant for the UK in a Changing Europe initiative and teaches research methods at the University of Sheffield.

James Dennison is a PhD candidate at the European University Institute, Florence. His research interests include political participation, European politics and longitudinal methods. He is currently a Research Assistant for the UK in a Changing Europe initiative and teaches research methods at the University of Sheffield.

[i] Since this blog was first written, other polls have suggested a hardening of Eurosceptic opinion in Great Britain with the reverse in Northern Ireland.

[ii] I forgo 2015 party choice because of the high correlation between this variable and religious denomination for the four largest parties as shown below in bold.

| Religious breakdown of party voters in the 2015 UK General Election in Northern Ireland (source: 2015 Northern Ireland General Election Survey) | ||||

| Catholic | Protestant | Other/None | Total | |

| DUP | 1.2 | 90.4 | 8.4 | 100 |

| Sinn Féin | 91.1 | 2.1 | 6.8 | 100 |

| UUP | 1.1 | 86.7 | 12.2 | 100 |

| SDLP | 84.2 | 4.5 | 11.3 | 100 |

| Alliance | 31.1 | 40 | 28.9 | 100 |

| Other | 25.6 | 49.8 | 24.6 | 100 |

[iii] Though higher age, education and Catholicism all reduce ambivalence/indifference about the EU, as shown in the second model, below.

[iv] Determinants of attitudes to the EU in Northern Ireland: Multinomial logit model

| Comparison Group: Wish to Remain in the EU | Wish to Leave | Don’t Know/Neutral/ Refused to answer |

|---|---|---|

| Religious identity (ref. category: other/none/refuse) | ||

| Catholic | -0.464** | -0.658*** |

| (-0.214) | (-0.181) | |

| Protestant | 0.763*** | 0.264 |

| (-0.198) | (-0.173) | |

| Religiosity | -0.0633 | -0.0187 |

| -0.0455 | -0.0408 | |

| Age | 0.000374 | -0.0126*** |

| (-0.00425) | (-0.00386) | |

| Income (ref. category: below £10000) | ||

| £10000-£20000 | -0.178 | -0.302 |

| (-0.266) | (-0.243) | |

| £20000-£30000 | 0.0378 | -0.178 |

| (-0.259) | (-0.238) | |

| £30000-£40000 | -0.178 | -0.0934 |

| (-0.296) | (-0.264) | |

| Above £40000 | -0.779* | 0.0938 |

| (-0.466) | (-0.345) | |

| Refused to say | 0.279 | 0.488** |

| (-0.239) | (-0.217) | |

| University Degree | -0.0119 | -0.404** |

| (-0.207) | (-0.191) | |

| Constant | -0.783* | 0.719* |

| (-0.451) | (-0.396) | |

| Observations | 1607 | 1607 |

| Standard errors in parentheses | ||

| *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1 | ||