The 1975 referendum posed a difficult challenge for government: how could it ensure an informed public debate, without being seen to prejudice the result? Eurosceptics have described the conduct of that referendum as a “sham”, partly because of Harold Wilson’s decision to establish a Referendum Information Unit at the Cabinet Office. Lindsay Aqui argues that the government’s reluctance to make a positive case for membership stemmed from worries about perceived bias. Indeed, Britons’ historic lack of enthusiasm for the EU may have its roots in the tepid Yes campaign of 1975.

The 1975 referendum posed a difficult challenge for government: how could it ensure an informed public debate, without being seen to prejudice the result? Eurosceptics have described the conduct of that referendum as a “sham”, partly because of Harold Wilson’s decision to establish a Referendum Information Unit at the Cabinet Office. Lindsay Aqui argues that the government’s reluctance to make a positive case for membership stemmed from worries about perceived bias. Indeed, Britons’ historic lack of enthusiasm for the EU may have its roots in the tepid Yes campaign of 1975.

In the referendum of June 1975, 67% of voters opted to remain in the European Community. Prime Minister Harold Wilson called it an “historic day, one that had settled 14 years of arguments.” Far from it, however: the referendum threw into question the basis upon which Britain joined the Community and injected even more uncertainty into a largely ill-informed public debate. The result of the referendum has been referred to as an unenthusiastic vote for the status quo, and it seems that despite voting yes the public was unconvinced of their choice. That result begs an important question: why was Britain’s public in favour of, yet ambivalent about, Community membership?

The government’s information policy

After much deliberation, it was decided that the best method for providing information to the public about the referendum would be through a centralised information unit. For ten weeks, the Cabinet Office Referendum Information Unit served that purpose. The minister responsible for the Unit was Foreign Secretary James Callaghan. He thought ‘the key to success for the unit was to maintain a low profile’. There appear to be two likely reasons why Callaghan advocated this approach.

First, ensuring the effective use of the reduced government advertising budget was a small but important consideration. Second, and a much more prominent consideration, was the very real possibility that a government information campaign might be interpreted as a propaganda effort, exposing the government to the accusation that the vote had been biased. In the parliamentary debate on the referendum, the question of whether the government had considered this risk was a prominent concern. One MP described the unit as ‘something rather sinister’.

On the other hand, Cabinet Office officials had evidence to suggest that the British population needed more knowledge of the pros and cons of British membership if they were to feel they had voted responsibly. Callaghan was thus handed the difficult task of creating an informative campaign that avoided the kind of information that could lead to the government being accused of leading the vote. To ensure this objective was met, the Unit operated under particular constraints and could not proactively engage with the public.

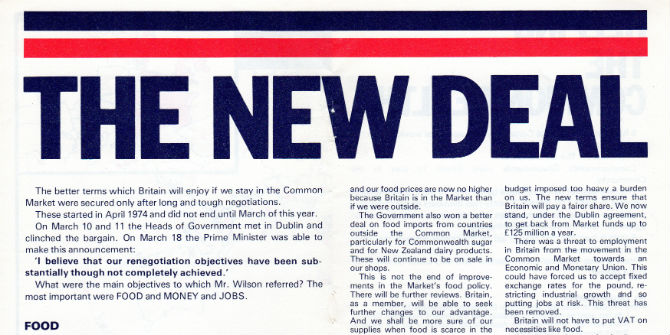

One exception to the Unit’s restrictive mandate was the creation and distribution of a popularised version of the government’s white paper on the renegotiation. The 15-page publication, entitled Britain’s New Deal in Europe outlined the government’s rationale for recommending a yes vote. It was distributed to 21.65 million households between 26 and 31 May, in a package including copies of the official pamphlets from Britain in Europe and the National Referendum Campaign. This arrangement was due to agreement reached in Cabinet that, in order to conduct the campaign fairly, the government had to ensure voters were given equal access to arguments on both sides.

Opinion polls and the probability of a yes vote

Despite the rationale for a low-key campaign, there were persuasive arguments in favour of a more vigorous effort to persuade public opinion. An article in The Economist, for example, argued strongly that a government recommendation to stay in would be persuasive for undecided voters. So why then did the Wilson government not attempt to capitalise on its own potential influence?

In addition to writing and publishing Britain’s New Deal in Europe, the Unit was responsible for reporting trends in public opinion. Their reports were based on private polling done for the prime minister and polls in newspapers. Over the course of April and May the Unit consistently reported that the ‘yes vote’ was leading in the polls. One report in May indicated that the figures of respondents in favour of membership had not dropped below 55%.

Though it may seem counter-intuitive, the coverage of the campaign to leave the Community boosted the government’s confidence. The Unit found that the more frequently controversial politicians, such as Tony Benn and Enoch Powell, discussed the issue, the more public opinion swung in favour of maintaining membership. The consistently positive outlook reported by the Unit gave those who had advocated a more enthusiastic campaign confidence that the low-profile approach was not a risky policy.

The impact of government information on public opinion

It is difficult to discern the impact of the government’s information campaign on public opinion because its influence would be nearly impossible to disentangle from the other campaigns. However, there is reason to suggest that the tactics employed by the Wilson government, and previous governments, in their communication with the public about European integration had played a role in shaping Britain’s unenthusiastic mood. The Wilson government’s campaign relied on negative arguments about the inherent risks of leaving the Community. The pamphlet argued that, if the public voted no, ‘there would be a risk of making unemployment and inflation worse’ and that the UK would be relegated to the status of ‘outsiders looking in’. Britain’s New Deal in Europe suggested that it was not worth the risk of leaving the Community, yet hardly espoused the benefits of remaining ‘in’.

Focusing on the risks of being outside the Community was not a new strategy. The Heath government had used similar tactics to persuade public opinion in favour of the application in 1971. Prominent campaign slogans included ‘since we cannot beat them we must join them’ and ‘there is no sensible alternative.’ Though it would push the argument too far to suggest that Britain’s lack of enthusiasm rests entirely on the shoulders of one campaign, it is doubtful that such tactics mustered any genuine enthusiasm for the cause.

Those who pressurised David Cameron to commit to a renegotiation and referendum made it one of their claims that the 1975 referendum was a sham. Nigel Farage in particular believes it was a ‘majority attained by fraud’. These kind of accusations are perhaps understandable given the lack of an impassioned defence of Britain’s Community membership on the part of the Wilson government. But to suggest that the official information campaign was a deliberate attempt to mislead the public discounts the rationale underpinning the Wilson government’s information policy.

The 1975 referendum holds a significant lesson about the responsibility shouldered by any government which chooses to use a referendum as a democratic device. Not only is the government the body which must ensure the fair conduct of the referendum, it must also offer sufficient information about complex and sometimes obscure policy issues in order for the public to feel they have made an informed choice. Constructing an information policy which can fulfil both criteria is a delicate task. It is also a task which has the potential to yield few results. Despite the majority that voted in favour of membership in 1975, that result certainly did not settle the debate over Britain’s place in Europe.

For those about to embark on campaigns to sway the public on the issue of EU membership, the question of how to engage the public in a constructive debate about European integration remains particularly challenging.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the BrexitVote blog, nor the LSE.

Lindsay Aqui is a second year PhD Candidate in history and politics at Queen Mary University of London. Her thesis, An Exceptional Case: Britain, Renegotiation, Referendum and the European Community, explores the UK’s relationship with the Community from entry in January 1973 to the referendum in June 1975. This article is based on her contribution to The Mile End Institute conference, Britain and Europe: The Lessons from History, which was funded by UK in a Changing Europe.