Britain’s first attempt to join the EEC was thwarted by Charles de Gaulle. Piers Ludlow argues that the long and laborious process of negotiating the UK’s entry is relevant to the Brexit debate. Firstly, it is useful to remember why Britain felt the need to join the European club. Secondly, it is a reminder that states which wish to join must adapt to the EU’s rules, rather than the other way around. And even in 1961 the polarising effect of ‘Europe’ on British political debate was beginning to be felt.

Britain’s first attempt to join the EEC was thwarted by Charles de Gaulle. Piers Ludlow argues that the long and laborious process of negotiating the UK’s entry is relevant to the Brexit debate. Firstly, it is useful to remember why Britain felt the need to join the European club. Secondly, it is a reminder that states which wish to join must adapt to the EU’s rules, rather than the other way around. And even in 1961 the polarising effect of ‘Europe’ on British political debate was beginning to be felt.

Britain’s first application to join the EEC was made over half a century ago, in July 1961. Thanks to President Charles de Gaulle’s intervention, the membership bid failed. In the wake of the General’s celebrated – or infamous – press conference of January 14, 1963 at which he issued the first of his two vetoes of British membership, the application was frozen indefinitely. Britain’s wait on the margins of the integration process would continue for a decade more.

It might therefore seem worth asking whether a failed application so far in the past has any real relevance to today’s debate about Britain and Europe? This post will suggest that there are at least three reasons why it does still matter.

The first reason is the light that the application sheds on the motives that pushed the United Kingdom to apply for membership of a club from which it had originally stood aside.

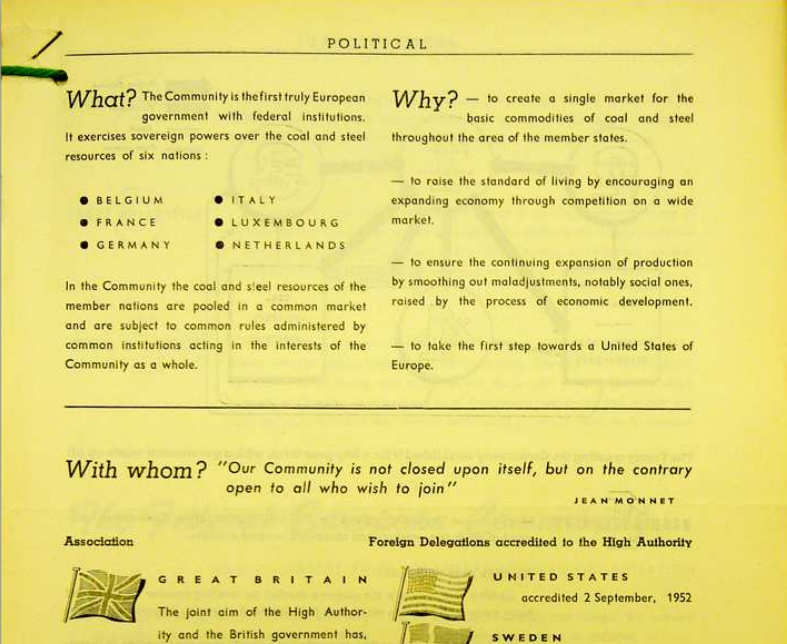

The internal government debate that preceded Harold Macmillan’s decision to seek membership featured a cocktail of economic and political motivations. Prominent amongst the former was the belief that by entering the EEC, the UK might be able to swap its erratic ‘stop-go’ economic performance for the sustained and rapid growth enjoyed by most of the EEC’s six founder members, West Germany and Italy in particular.

Also significant was anxiety about the implications of Britain’s long-term exclusion from the large and prosperous single market emerging on its doorstep.

As important were fears of political marginalisation, if, as then seemed likely, the EEC developed into a potent political actor. Britain’s position in the world had already been hard-hit by the disappearance of its Empire; Macmillan’s government could not stand idly by while a new global player grew up next door.

The prospect of being able to steer Europe from within also had its appeal, following a period when the British had failed repeatedly in their attempts to influence from without the direction of travel taken by the ‘Six’ – i.e. the six founder members of the EEC.

Club rules

A second reason for revisiting the first abortive membership bid is that it was an occasion on which both the UK and its European partners learned a great deal about the realities of Community enlargement. These lessons were slow and painful for both parties. But many are of continuing relevance.

The most basic was that when a state applies to join the European Community/Union the onus of adaptation falls almost wholly on the applicant rather than the EC/EU.

This was not what the British had expected prior to 1961-3. Nor was it what the many continental supporters of British membership had wanted or anticipated.

But almost as soon as the negotiations got under way it became clear that these were not talks between equals, with give or take expected on both sides, but instead a process where the British had to demonstrate how they would adapt to the Community system and to justify the slightest deviation, almost always temporary, from the acquis communautaire – i.e. the corpus of pre-existing laws and agreements the Six had reached amongst themselves.

This was not the result of malice or ill-will on the part of the Six. On the contrary, most of the then member states were delighted at the prospect of Britain joining their number.

But it was instead an inevitable reflection of the fact that agreements within the Community had been laboriously and painstakingly stitched together amongst the Six and could not be unpicked simply because they were ill-suited for the aspiring member. As a result, it was for the applicant to conform to club rules, not the duty of the club to rearrange the furniture better to suit the potential new arrival. A clearer illustration of the fundamental difference between negotiating in Brussels as an insider, and trying to do the same as an outsider, would be hard to find.

Fissile effect

A third reason why the 1961-3 application still matters is that it highlights how uniquely divisive the European question has been for Britain since the very outset of the integration process.

Britain’s position in the world had already been hard-hit by the disappearance of its Empire; Macmillan’s government could not stand idly by while a new global player grew up next door. The question of whether or not to join the then fledgling Community divided both the Conservative and Labour parties, and split most other elite groups in the country, whether the civil service, academia, the leaders of business etc.

It did so moreover in a somewhat peculiar manner, with the comparative indifference or agnosticism of the majority (whether of the public at large or most component groups that make up the British population) standing in sharp contrast to the fierce enthusiasm or antagonism of the pro and anti-wings.

From the outset, in other words, ‘Europe’ became a cause that for the majority seemed unimportant, even boring, whereas for a sizeable minority on each side of the argument, it became either an absolute necessity or a total abomination. Hugo Young once wrote of the ‘fissile effect’ that the issue went on having on both Labour and the Conservatives, referring primarily to the way in which both parties became split between pro- and anti-Europeans.

But almost as remarkable was the divergence between those for whom Britain’s place in Europe was a vital matter, and the many others for whom it was an issue of little interest or importance. This capacity to bore many, but to enthuse some, and repel others, has persisted to this day.

Divisive too was the question’s effects on Britain’s main international partners. The United States and most of Britain’s closest geographical neighbours were strongly in favour of the UK joining the EEC; much of the Commonwealth meanwhile was hostile and anxious about the negative effects that EEC membership might have on the still important flows of trade between Britain and its former empire.

Fragility and complexity

Looking back also helps clarify how much has changed – thereby warning those inclined too easily to draw simple ‘lessons from history’ – but also which features of the relationship have remained more constant.

The lure of Europe as an area of booming economic growth has long since faded; from a 21st century perspective, it is Europe’s economic fragility that looks a more significant factor in the Britain and Europe debate than Europe’s economic dynamism.

Another substantial difference, is the complexity of today’s EU compared with the much smaller, simpler, and less powerful EEC to which the Macmillan government applied. Leaving the modern Union would have knock-on effects in policy areas totally unaffected by the integration process back in the 1960s.

And finally the difficulties of Britain’s four decades and more of Community/Union membership become somewhat easier to understand when it is realised that since belatedly joining in 1973, the UK has seldom been able to acquire a share of the leadership of EC/EU that had been taken for granted by all of the British leaders who sought to join the club, whether Macmillan, Harold Wilson or Edward Heath. The direction of travel of the integration process has gone on seemingly being determined by others, despite the fact that Britain has been a member of the EC/EU for over 40 years.

Yet for all these very substantial changes, certain questions remain as apposite today as they were when faced by Harold Macmillan’s government at the start of the 1960s. How will the British economy fare if it is excluded from its closest and largest market? What impact would such exclusion have on Britain’s economic relationship with other major economies? How easy would it be for Britain to stomach a situation in which its global political clout was dwarfed by the collective weight of an EU within which it no longer had the voice and the influence that derives from membership? Or would its freedom from the limitations and compromises inevitably involved in multilateral decision-making allow the country to find a new role as a smaller, but more nimble, actor on the global stage?

The fissile effect of such questions looks set to continue.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the BrexitVote blog, nor the LSE.It was first published by Queen Mary University of London’s Mile End Institute as part of Britain and the European Union: Lessons from History.

2 Comments