Brexit poses significant challenges to Whitehall, and raises questions about whether the Civil Service is up to the task of negotiating a new settlement for Britain’s place in the world, write Dave Richards and Martin Smith. Outlining the development of Whitehall reforms, they explain why a very different ministerial-civil service relationship is needed, as well as an overhaul of the Westminster Model.

Brexit poses significant challenges to Whitehall, and raises questions about whether the Civil Service is up to the task of negotiating a new settlement for Britain’s place in the world, write Dave Richards and Martin Smith. Outlining the development of Whitehall reforms, they explain why a very different ministerial-civil service relationship is needed, as well as an overhaul of the Westminster Model.

The repercussions of Brexit have already led to a series of new grand designs to Whitehall’s architecture that even Kevin McCloud might struggle to explain in a pithy refrain. As we have argued in an earlier blog, despite the unprecedented turbulence caused by the referendum, the political class remains committed to the Westminster Model while it navigates a new settlement for Britain’s place in the world. The challenges facing the Civil Service in this venture are legion, but is it up to the task and is its formal relationship to its political masters appropriate for such an undertaking?

In a new article for Governance, we explore the extent to which forty years of reform has eroded the traditional understanding of the minister-civil servant relationship. The original tenets underpinning the relationship, established by the 1918 Haldane Report, affirmed the earlier Northcote-Trevelyan principle that the relationship should be indivisible. This was based on the convention that officials advise a minister on a subject and as such, there is no requirement for the separation of power between the political and administrative class.

The Haldane convention established the modus operandi that officials and ministers should operate in a symbiotic relationship whereby ministers decide after consultation with their officials whose wisdom, institutional memory and knowledge of the processes of governing helps to guide the minister.

But since the 1970s, the cumulative impact of reforms undergone by Whitehall has embedded a very different type of relationship to that presented by Haldane. A flavour of this shift is captured in the various contradictory positions offered by politicians in the framing of their view of the bureaucratic class:

- ministers constantly pay lip-service to the Civil Service’s ability in terms of support and intellectual excellence while at the same time criticising it for lacking the appropriate skill-sets for the twenty-first century;

- officials are portrayed as first-rate policy designers, yet conversely caricatured as ineffective policy implementers;

- ministers still invoke the hackneyed analogy of Whitehall as a ‘Rolls-Royce-like’ machine, but are then swift to blame it for multiple policy failures, often in terms of an inability to devise policies that effectively translate into ‘real world’ outcomes.

Such views do little to convince the external world that ministers and civil servants still view their own relationship as the trusting and unified dyad of Westminster folklore.

The reforms introduced over recent decades – often discussed under the label of New Public Management – lead us to conclude that what today has emerged in all but name is an accountability-based, principal-agent relationship between civil servants and their political masters that is far removed from the original Haldane convention.

The process started under Thatcherism which, partly informed by public-choice accounts of bureaucracy, has shaped the way post-1979 governments view the Civil Service in a more adversarial light. Whitehall was to be seen as a partner in the policy process, but only in the context of a particular notion of ‘party sovereignty’ – it was there to implement the will of the government. Failure to do so was portrayed as an entrenched unwillingness to politically engage with the Thatcherite project, or as managerial incompetence. The idea that officials had a role in mediating ministerial preferences was challenged head-on. Thatcherism politicised the minister-civil servant relationship by overseeing a shift from mutual dependence to conflict. The Civil Service, in this sense, joined the ‘enemies within’, they were “not one of us”, and were seen as a constraint on the Thatcherite project.

All post-1997 governments have embraced a similar critique of Whitehall. The period of Whitehall reform under New Labour led to considerable changes unfolding across the civil service. Notable examples include:

- significant increases in special advisers (especially around the prime minister);

- a much greater focus on implementation through the Prime Minister’s Delivery Unit;

- increased use of private suppliers in the delivery of public services;

- a greater use of targets and market mechanisms as methods for controlling agents.

Since 2010, governments have adapted New Labour’s reform agenda, so moving further away from Haldane. Ministers have sought to increase their power over the senior civil service through particular mechanisms of managerialism and accountability, including:

- the rise in political advisors (38 in 1997, 74 in 2010, and 107 by 2015);

- the introduction of extended ministerial offices;

- an increased role for ministers in appointing Permanent Secretaries – this change raising questions over the principle of neutrality and whether senior officials seeking appointment to this level would continue to ‘speak truth unto power’ for fear of promotional non-preferment;

- changing the rules under which civil servants give evidence to Select Committees;

- the introduction of performance objectives for individual Permanent Secretaries which challenges the Westminster Model’s conception of individual ministerial accountability;

- the introduction of Departmental Business Plans – replacing Labour’s Public Service Agreements – to offer a different form of control and accountability. ‘Priorities’ and ‘transparency’ became the new lingua franca of public services as Whitehall was tasked with shifting from ‘bureaucratic accountability to democratic accountability’.

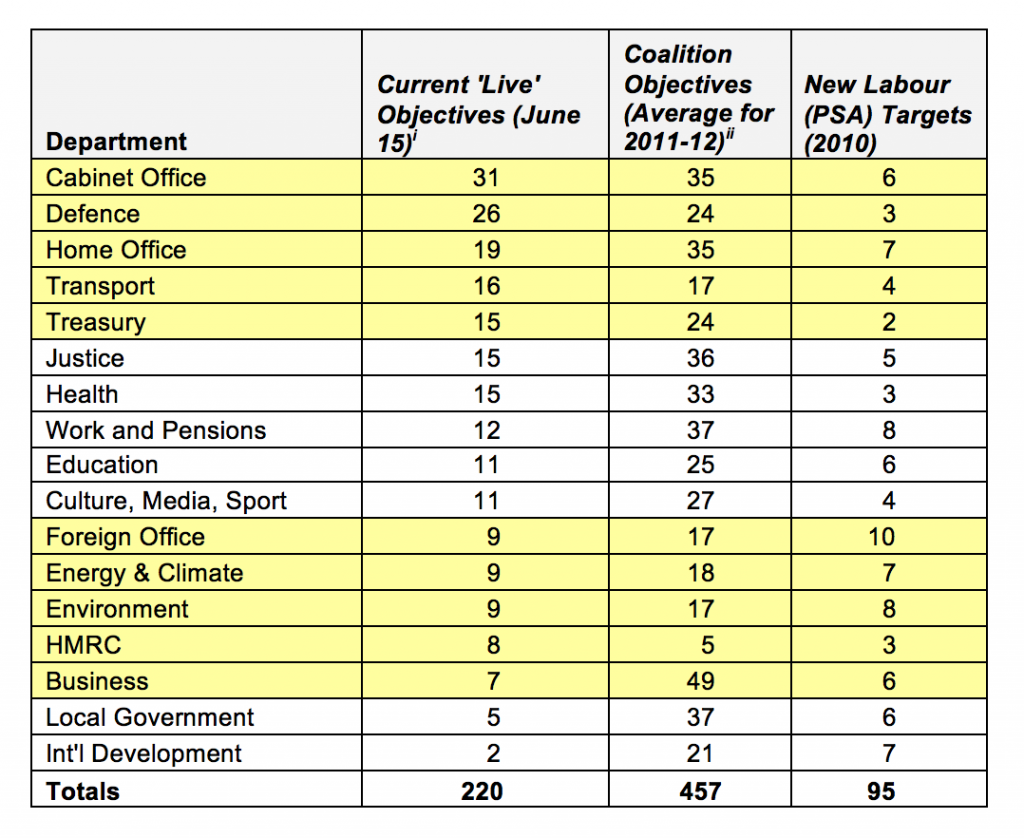

In practice, as Table 1 reveals, little changed in terms of a target culture thriving across Whitehall.

[i] Data taken from all Govt. departments ‘business reports’ and departmental publications (available via gov.uk). ‘Objectives’ defined as either stipulating a numerical aim within the department’s remit, or the necessity of further specific action(s) to achieve a policy aim or goal, all recorded ‘targets’ were live (i.e. not complete) at the time the data was sourced.

[i] Data taken from all Govt. departments ‘business reports’ and departmental publications (available via gov.uk). ‘Objectives’ defined as either stipulating a numerical aim within the department’s remit, or the necessity of further specific action(s) to achieve a policy aim or goal, all recorded ‘targets’ were live (i.e. not complete) at the time the data was sourced.

[ii] Original data drawn from C. Talbot

Rhetorical claims that bureaucratic accountability has been abandoned at the behest of democratic accountability would seem misplaced. Instead, a fundamental change in the relationship between ministers and civil servants has occurred; a shift from interdependence to a binary mode of separation, based on a principal-agent model. Ministers have sought to download accountability while at the same time protecting against a diminution in the power they wield. At the same time, they have avoided addressing questions on the constitutional implications implied by these reforms. Their approach has been to argue that reform is wholesale, yet maintaining that the Westminster Model remains intact. Anything else would require the need to re-imagine the long-established constitutional certainties underpinning the British approach to governance.

In a post-Brexit world, the role of the Civil Service is potentially shifting towards that of an ‘overseer’. It needs to oversee contracts, accountability and democratic processes, and ensure equity in a devolved and fragmented system. The primary function of officials is no longer just that of policy-making, but also as regulators of the policy process. Given the absence of veto-players in the Westminster system, this becomes a crucial dimension. Yet, evidence suggests that the reforms discussed above and their impact on the minister-civil servant relationship is constraining the latter’s veto-playing function.

The world of Haldane may have long-gone. In the twenty-first century, a new breed of civil servant is required with a different relationship to their political masters. Change could, for example, involve an organisational and cultural shift from a departmental-focused to a problem-focused approach which is more flexible, smaller and digitally based.

This would require a fundamental move from hierarchical bureaucracy to what we would label ‘cybernetic-squad’ bureaucracy. A recognition that in a post-Brexit world, there are certain, specialised bureaucratic/technical skills that are not linked to departmental functionalism, but which need to focus on specific problems, allow for flexibility, and rapid intervention. Expertise would no longer be located within a department, but to teams deployed to deal with particular projects or intractable problems. It would, however, require a very different ministerial-civil service relationship and more particularly, an overhaul of the Westminster Model.

Note: The above draws extensively on a longer article by the authors in Governance entitled ‘The Westminster Model and the “Indivisibility of the Political and Administrative Elite”: A Convenient Myth Whose Time Is Up?’. This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. It first appeared on the BPP blog. Image credit: OliBac CC BY

Dave Richards is Professor of Public Policy at the University of Manchester.

Martin Smith is Anniversary Professor of Politics at the University of York