British Prime Minister Theresa May’s upcoming visit to Beijing is part of London’s efforts to build “Global Britain” by forging new trade partnerships beyond the EU. Yu Jie (LSE) says both sides have good reasons to want closer engagement in trade and investment, even though they remain poles apart politically. The Prime Minister should grasp the opportunities on her visit to China this month, she contends.

British Prime Minister Theresa May’s upcoming visit to Beijing is part of London’s efforts to build “Global Britain” by forging new trade partnerships beyond the EU. Yu Jie (LSE) says both sides have good reasons to want closer engagement in trade and investment, even though they remain poles apart politically. The Prime Minister should grasp the opportunities on her visit to China this month, she contends.

“Brexiteers” claim to be encouraged by friendly noises from potential bilateral trade partners. But these are mainly former colonies, mostly small or in Australasia, whose modest markets are now part of the Chinese economic orbit. Apart from US President Donald Trump, whose enthusiasm for Brexit appears both frivolous and mischievous, it is China and the other emerging economies which really matter.

Beijing was perplexed by Britain’s vote to divorce with the EU. China was embarrassed by having hailed the so-called “golden era” of bilateral relations with the UK, only to see Britain veer off in a totally new direction, apparently without a clear agenda or an exit plan. All their suspicions about the dangers of Western democracy were confirmed in spades. A more pertinent lesson for the Chinese Communist Party is the danger of externalising internal party conflicts, as the Conservative Party has done with Brexit.

A pertinent lesson for the Chinese Communist Party is the danger of externalising internal party conflicts, as the Conservative Party has done with Brexit.

China is very clear on what to ask for from the current British government. First, that the UK continues to provide a secure home of investment opportunities for Chinese companies, to enhance their brand value or for new acquisitions, without the fierce resistance encountered in continental Europe and the United States.

Second, potential support in any confrontation over trade with the US under Trump. If there is conflict, China will need to build alliances with Western powers more committed to the principles of free trade and globalisation, like the UK, though not at the expense of relations with the remaining 27 European Union members.

Third, for the UK to act as a cheerleader for China’s global ambitions, for example the “Belt and Road Initiative”, as George Osborne did with the UK’s membership of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Beijing is eager to be recognised by established economies. None of these three things would necessarily harm the British economy.

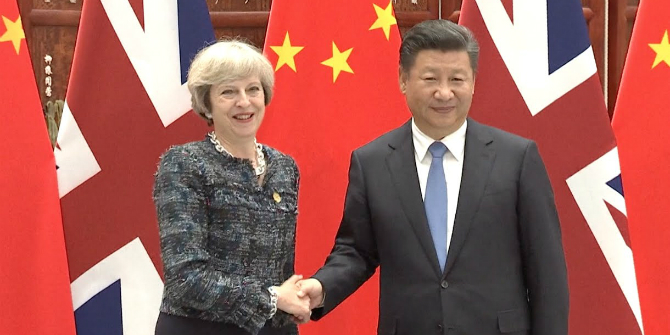

Image from YouTube, (CC license).

Since the UK’s Brexit referendum, China itself has also experienced seismic updates in domestic politics. Xi Jinping cemented his power as party general secretary in October last year, and China has championed economic globalisation, with ambitious goals to ensure it becomes an even greater global power. Ironically, Xi achieved what “Queen Theresa” sought with her snap election in 2017 – a “strong and stable” government.

Xi achieved what “Queen Theresa” sought with her snap election in 2017 – a “strong and stable” government.

But, after 40 years of economic reform at home and a bold opening to the global economy during the 1990s, the Middle Kingdom faces a new set of challenges and is asking itself where it might be heading. A close examination of Xi’s speech at the 19th party congress suggests that the Chinese Communist Party is shifting its focus of “principal contradiction”, a concept in communist dogma that defines its most pressing issue. The party knows it needs to run a successful and sustainable economy because the conventional, highly polluting, investment-driven model has not only run out of steam, but has also created huge income disparities and a lack of social mobility.

This is part of the reason the Chinese leadership went out on a limb promoting the UK, ahead even of other major European economies, such as France and Germany. That prioritisation was dictated not by sentiment but a hard-headed calculation that while France and Germany have been important for providing manufacturing technologies, the UK is more useful for the next stage of Chinese development: a shift to a service-based economy, the move to currency convertibility via renminbi trading in the City of London, and absorbing and welcoming Chinese investment.

At present, UK exports to China remain at a modest level.

At present, UK exports to China remain at a modest level. Beijing has long admired British expertise in financial and corporate governance, but they remain less likely exports than “tourism and education”, which a Chinese tabloid once famously mocked the UK as all it was good for. Even in the eyes of Mao Zedong, Britain was seen as an advanced industrial economy that China aspired to become in 1958.

Meanwhile, a dangerous mixture of China’s historical humiliation and its staggering economic success has unfortunately bred a strong sense of complacency on one level and an equally powerful current of hubris on another. This could turn out to be lethal inside China as well as detrimental to its neighbours and distant great powers. The UK is traditionally viewed by the Chinese as a former colonial power which inflicted humiliation on China in the Opium Wars. The ongoing thorny issue of Hong Kong will remain.

China and the UK have very different political systems and institutional establishments. It is naive to assume that Xi’s China will have any resemblance to a liberal democracy like the United Kingdom. I do not suggest London subscribes to the Communist Party’s propaganda following Xi’s “Chinese dream”. Instead, May should use the visit to explore an unconventional choice of partner, one which sees economic prosperity as the only means to ensure its survival. If No 10 Downing Street assumes Britain can prosper outside the EU, China is an odd yet indispensable partner to have.

This article represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. It also appeared in the South China Morning Post.

Dr Yu Jie is head of China Foresight at LSE IDEAS, the foreign policy think tank of the London School of Economics and Political Science