How does the rest of Europe see Brexit? In this extract from a Reuters Institute report, Alexandra Borchardt (left), Diego Bironzo and Felix M Simon examine what preoccupies the UK’s neighbours. They find trade and the economy has been core to the coverage, with Irish media focussing on Northern Irish border issues, but relatively little interest in migration.

How does the rest of Europe see Brexit? In this extract from a Reuters Institute report, Alexandra Borchardt (left), Diego Bironzo and Felix M Simon examine what preoccupies the UK’s neighbours. They find trade and the economy has been core to the coverage, with Irish media focussing on Northern Irish border issues, but relatively little interest in migration.

The EU was founded on shared economic interest, but its vision has always been political. After the end of World War II, political leaders, determined to not let Europeans wage war against each other ever again, started to build a network that was more than just diplomacy. The Coal and Steel Community was the first association knitting together European countries in 1951. Six years later, the Treaty of Rome marked the birth of the European Economic Union; the founding members were France, Italy, Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany.

The expansion of the EU was also often driven by economic considerations: battling the oil crisis, supporting financially weaker regions at the periphery, integrating Eastern European members after the fall of the Iron Curtain. The creation of the Eurozone in 1999 and the introduction of the euro as common currency in 2002 marked other stepping stones where shared economic interests were supposed to foster political convergence.

So it comes as no surprise that issues around the economy, business, and trade are at the core of media coverage of Brexit. Almost every second piece that dealt with specific issues had something to do with business, trade, and the economy (44%). From January to April, economy, business, and trade were mentioned even more often than negotiation-specific topics (which include coverage of the state of the negotiations, the negotiations meetings, and negotiation issues such as Northern Ireland, the so-called Brexit bill, and the transition period). About two-thirds of the complete coverage focused on issues.

However, a major part of the coverage did not deal with specific topics: 35% of the coverage was explicitly focused on the Brexit negotiations between the EU and the UK. The negotiation-specific coverage predominantly dealt with the state and progress of the actual negotiations (26.2%), followed by meetings in Brussels (14.7%), Northern Ireland (13.9%), and the transition period (10.5%). What is a little bit more surprising is that reporting about migration from non-EU countries into the EU, as well as the right of Europeans to move to other EU countries, took up very little room, a mere 10% of all issue-related coverage. Security and defence played a role in just 1% of the issue-related coverage. Interestingly, sovereignty (that is, an EU country’s ability to make its own laws and decisions independent of the EU, a key issue for many Brexit supporters) was barely discussed at all (3%).

Our content analysis also allowed us to look at these topics at a more granular level, ranking the most relevant issues within each topic area. Looking at the more specific issues that drove the coverage, and excluding mentions about the progress of the negotiations or general references to Brexit, trade was by far the most discussed sub-topic.

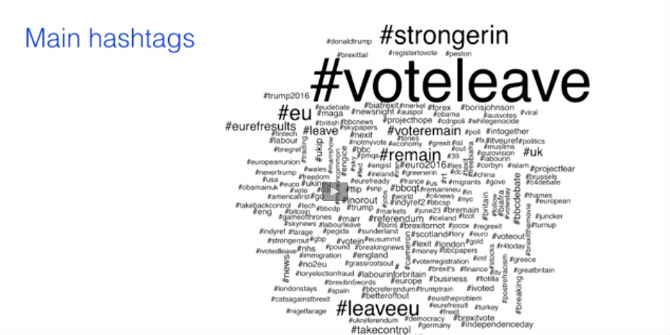

Taking the same approach, and examining the European media perspective on political topics relating to Brexit, we also identified an interesting mix of sub-topics. Developments within the Conservative Party were the most discussed, but the EU referendum campaign also kept being referenced by the media, often to compare and contrast some of the claims made during the campaign with the reality of the negotiations and the updates provided by the likes of Theresa May, Boris Johnson, and Jeremy Corbyn through their Brexit addresses. The Withdrawal Bill and its implications were also covered extensively, as was the possibility of a second referendum on Brexit. The Labour party, instead, was seen as a rather minor issue in relation to Brexit, even if the June 2017 snap elections created some unexpected momentum for the party.

The discussion around migration and mobility, which took up 10% of all issue-related coverage, was instead dominated by the impact that Brexit will have on people’s freedom to move between Ireland and Northern Ireland (5% of all the issue-specific coverage). This was clearly an important topic for the Irish media, which drove more than two-thirds of it. The right of EU citizens to stay in the UK ranked second, receiving only 2.2% of all sub-topic mentions within the broad category of migration and mobility, which is less than the 3% of the overall coverage about the impact of EU standards and regulations on the EU 27.

When we further examined this topic from the perspective of the negotiations, its relatively minor importance in the media debate was confirmed, as it received only a further 2.4% of the coverage – far less than, for instance, Northern Ireland, the discussions on a transition period, the Brexit bill, and of course more general matters such as the progress of the negotiations and references to the meetings.

Our analysts also attributed a sentiment code to each topic analysed, allowing us to understand how the various issues were being discussed by the media and what the media’s general mood was in their Brexit coverage. In line with our other findings, we found that the media remained largely factual in discussing specific topics, such as the economy, in relation to Brexit (61% of the time). However, when the media evaluated them, their overall outlook was most often negative (62% of the time, versus only 20% positive and 18% mixed).

Negotiation-specific stories drove the highest ratio of positive coverage (just over 50% of the total), and drove particularly favourable evaluations in December, as the UK and the EU agreed that sufficient progress had been made in the negotiations. Although overall less visible than the negotiations, the economy drove the highest amount of negative assessments (39% of all negative evaluations). In particular, the risk of inflation, mostly from the perspective of the UK and UK households, topped the list of sub-topics with the highest share of negative evaluations. Other economy-related topics with a strong negative connotation were the exchange rate, the situation of the economy in general, specific concerns about the agricultural, fishing, and transportation industries, tariffs, and the job market. A commentary from Spanish El País sums it up nicely (Vidal-Folch 2017):

Almost all the prophecies formulated before the vote to leave the EU on June 23, 2016 have been fulfilled. Worse than thought. Since then, the pound has depreciated around 14%, without the corresponding export stimulus having improved growth. Salaries have dropped by 0.4% between August of last year and this one. The contribution of net foreign trade to growth, of three tenths, has fallen compared to the forecast, and the increase in investment has been less than expected. Worse still: inflation has grown around two points, and will end the year up 2.7%, much more than the recommended 2%.

More than half of the reporting on trade issues unsurprisingly came from Irish media, and Germany, with a vested interest particularly in the automotive sector, came in second. The coverage on business relocation was expectedly dominated by German, Irish, Italian, and French media. One big issue in this context was the relocation of the European Banking Authority (EBA) (Paris won over Frankfurt) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) (Amsterdam won over Milan and Dublin), a decision made in late November 2017. In Sweden, medical giant AstraZeneca’s refocusing of its activities from the UK to Sweden drew quite a bit of interest.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. It is an extract from the Reuters Institute report Interested but not engaged: How Europe’s media cover Brexit, where accompanying figures can be found.

Dr Alexandra Borchardt is Director of Strategic Development at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford.

Felix M Simon is a research assistant at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Diego Bironzo is an account director and data insights analyst at PRIME Research UK.