This week’s European Parliament elections are a battle for Europe’s future. In this blog, Thierry Chopin, Nicolò Fraccaroli, Nils Hernborg and Jean-Francois Jamet examine the evolution of political cleavages ahead of the vote and the potential impact of Brexit on their result. They argue the next European Parliament will be more fragmented independently of Brexit.

Political cleavages – that is, the key dividing lines structuring politics – are evolving in Europe. Traditionally, positioning on the left-right spectrum and on European integration, as well as national affiliations, have been key factors to form compromises and majorities at European level. However, this modus operandi is being challenged. Increasingly, views on salient issues such as immigration and societal values are shaping the political discourse, resulting in unconventional coalitions at national level. In a recent policy paper for the Jacques Delors Institute, we argue that these emerging dynamics will impact the upcoming European elections and thus the new political balance and direction in the European Union. But what will the new equilibrium look like and what is the impact of Brexit?

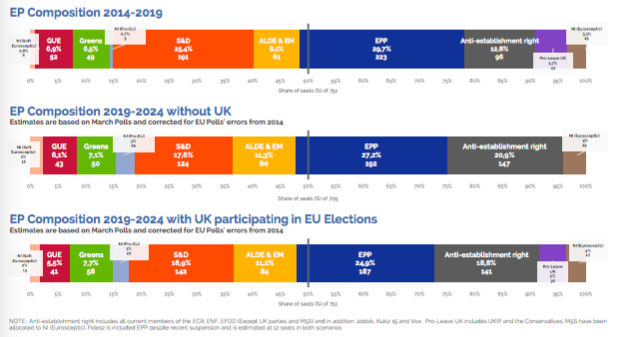

A key determinant will be the outcome of the European Parliament elections of 23-26 May 2019. According to our estimates, the next European Parliament (2019-24) will be more fragmented and less pro-European, and will contain a larger number of anti-establishment right-wing members. Figure 1 illustrates our estimates for the future composition of the European Parliament. Pro-European parties will likely hold a majority, though weaker than the current one. The centre-left (S&D) and the centre-right (EPP) will experience a significant decline in their share of seats and, in contrast to the current situation, will not be able to command a majority together. In addition, this composition would rule out also majorities based on ideological similarities, such as left (radical left, greens and S&D), centre-left (S&D, ALDE and greens), centre-right (ALDE and EPP) or a right wing (EPP and anti-establishment right) coalitions. The likely majority will be formed by pro-European groups, which require ALDE to join the EPP and S&D in appointing the new Commission. Importantly, these conclusions do not depend on Brexit: Figure 1 shows that with or without British MEPs in the European Parliament, the key implications of the upcoming elections hold.

Figure 1 – Composition of the European Parliament before and after the 2019 elections

Note: We use a more ‘cautious’ approach than existing projections to account for possible polling errors. For this purpose, we correct the results extrapolating polls errors witnessed in 2014 on the political group level. This results in giving more weight to Green and eurosceptic parties than existing polls as polls had underestimated the performance of such political formations in previous elections.

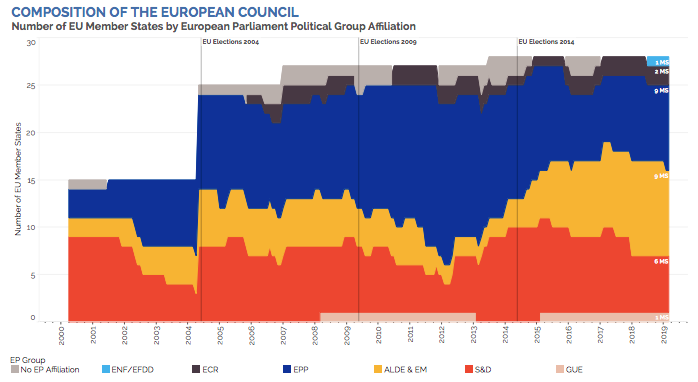

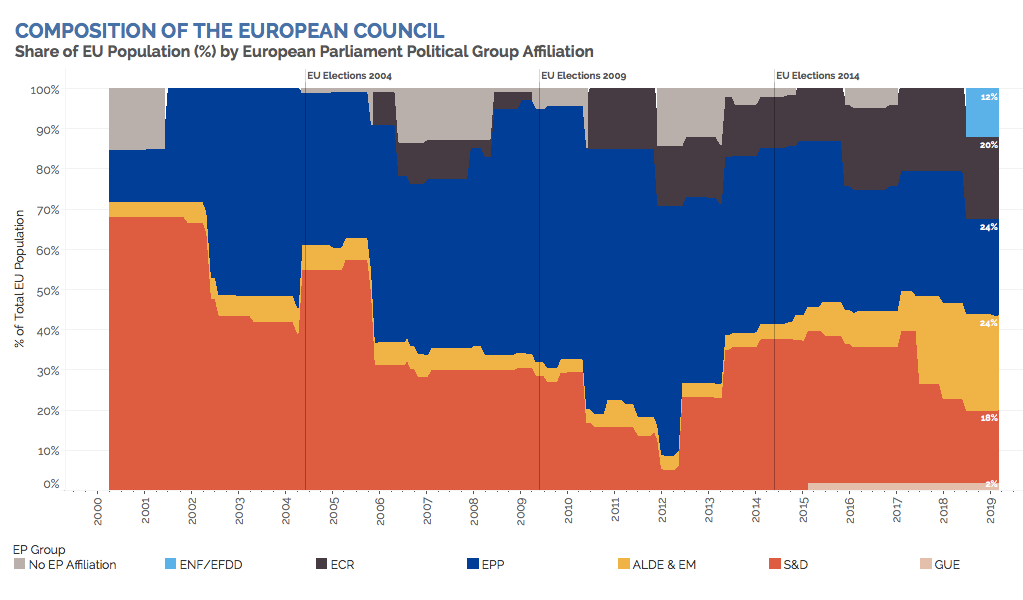

The new political balance of power in the EU can only be fully assessed by considering the current balance in the European Council, where S&D, EPP and the centrists/liberals (ALDE and Macron’s En Marche) also hold a qualified majority. Based on the party affiliation of each Member State’s head of state or government in the European Council, it is possible to compare the political balance in the European Council with the one in the European Parliament (Figure 2). As of March 2019, EU Member States had leaders affiliated to EPP (9), ALDE (9), S&D (6), GUE/NGL (1), ECR (2), ENF/ EFDD (1). Despite electoral victories for anti-establishment parties, for example in Italy, the representatives affiliated to pro-European groups (S&D, EPP, ALDE and En Marche) still made up more than 55 per cent of the Members representing at least 65 per cent of the EU population, which are the requirements to reach a qualified majority. In this context, the support of ALDE and En Marche in the Council and its swing role as part of the coalition in the parliament will be key for the appointment of the new Commission. There again, Brexit is not pivotal.

Figure 2 – Political balance in the European Council at EU28

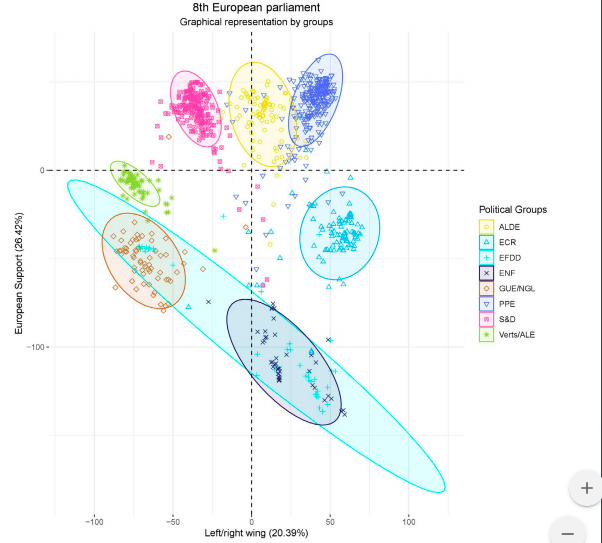

We further analyse whether traditional and new cleavages impact EU politics. In particular do traditional cleavages still have practical implications? Are categories such as left and right still useful to understand today’s politics? The answer to both from empirical evidence is “yes”. Cheysson and Fraccaroli (2019) have shed new light on the ideological transition in the European Parliament throughout the crisis. By collecting all roll-call votes from 2004 to 2019, they infer the main dimensions driving MEPs’ voting behaviour. Figure 3 shows the stances of political groups on the left-right and pro/anti-EU dimension during the current parliamentary term (8th European Parliament, 2014- 2019). Each dot represents a single MEP, coloured by her political group membership, and located according to her score on the two main dimensions. Their results show how the most important cleavage, i.e. the dimension able to explain the largest share of votes (26.42 per cent), corresponds to the pro/anti-EU dimension, whereas the second cleavage (20.39 per cent) corresponds to the left-right dimension.

Figure 3 – MEP’s voting behaviour in the 8th European Parliament (2014-2019)

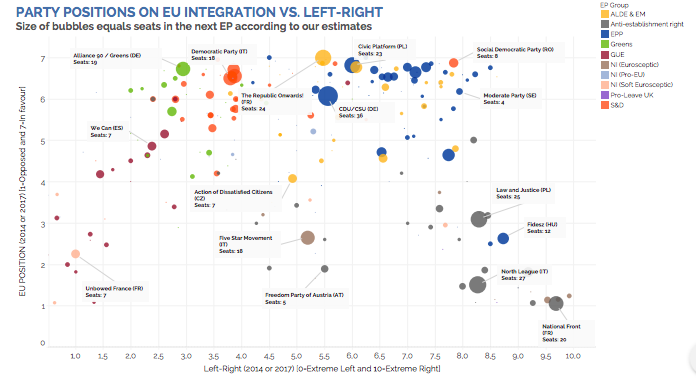

The continued relevance of the cleavage on European integration supports the finding that parties’ positioning on the issue is likely to act as a centrifugal force in coalition building in the European Parliament for the appointment of the Commission, at the cost of significant heterogeneity on the left-right spectrum. Figure 4 maps the position of individual national parties, together with their expected size and political group affiliation, according to their positioning on European integration (y-axis) and on the left-right spectrum (x-axis) according to the Chapel Hill Experts’ Survey. This chart can be compared to Figure 3, which showed the voting behaviour along the same dimensions of MEPs in the previous term. The figures thus indicate that, while other cleavages are emerging in Europe, the positioning on European integration is rather homogeneous and coherent among a majority of national parties. We therefore argue that this cleavage is the only one that can bring together the S&D, EPP and ALDE (and if necessary also the Greens) to make up a majority of MEPs.

Figure 4 – European parties’ stances on EU Integration and left-right spectrum

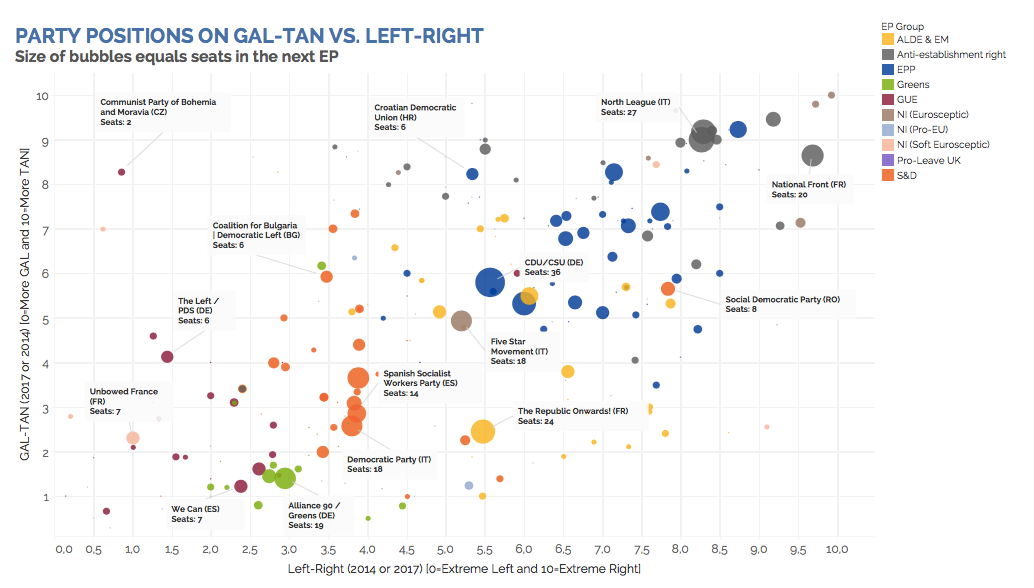

Nevertheless, while traditional cleavages such as views on European integration are still expected to play a role in forming a majority for the Commission, cleavages related to societal values are increasingly shaping the political discourse and views on salient issues such as immigration. These cleavages have been at the centre of the campaign and could be the basis for the formation of ad hoc majorities on selected topics in the next Parliament, just as the left-right cleavage was the basis for forming alternative majorities in the 2014-19 term. This is partly the result of a strategic shift from traditionally eurosceptic parties, which see more potential in advocating for European policies that reflect their ideologies rather than for an outright rejection of the EU. Currently, support for the EU and the single currency both stand at record high, and in such context eurosceptic parties seem to consider that the electoral gains from a merely anti-European discourse (anti-EU and/or anti-euro) have decreased. The structuring of the European political debate is therefore likely to be increasingly influenced by the cleavage between societal values opposing “cultural liberalism” and conservatism or even reactionary ideology. Importantly, positioning on societal values is correlated with the positioning on the left-right spectrum, and may therefore end-up reviving this dividing line (Figure 5). As a caveat, some parties like the AfD in Germany have tried to not entirely abandon their eurosceptic stance by conditioning support for their country’s continued membership of the EU on reforms in line with their political agenda. This approach of “reform or leave” is similar to that used by David Cameron before the Brexit referendum.

Figure 5 – European parties’ stances on EU Integration and GAL-TAN

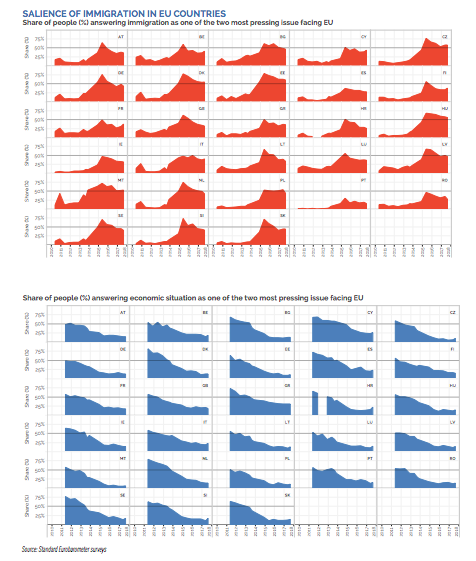

This also explains why eurosceptic political forces seek to promote at European level their fight on values and their political discourse on identity with its implications in terms of public policies, particularly in the field of immigration. Beyond political and economic factors, the strengthening of the anti-establishment right in Europe is linked to the impact of the migration crisis on the importance of the immigration issue for European public opinion: Europeans now consider immigration as the most important issue facing the EU according to Eurobarometer data, as shown in Figure 6. This policy issue remains higher on the agenda than the economic situation, which has been receding in most Member States since the peak of the economic crisis (Figure 6).

Figure 6 – Salient issues in EU Member States: immigration and economic situation

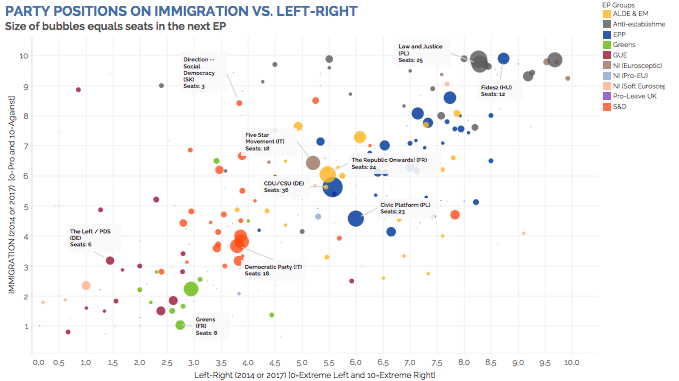

As the salience of immigration has risen, so have the political prospects for the parties further to the right, as these two cleavages are strongly correlated (Figure 7). Thus, while a stable majority based on the immigration cleavage seems unlikely as long as a majority in the EPP sticks to the current core EU values and support for further European integration (seen in Figure 4), centre-right and anti-establishment right parties might form ad hoc majorities based on their common ideological stance and positions on salient issues such as immigration and economic policy. Moreover, in specific policy areas such as on trade, the anti-globalist parties on the far-right and the far-left may take similar positions and coalesce in seeking to block agreements and legislative proposals. And where the anti-establishment right cannot achieve its aims by forming alternative majorities, they may seek to disrupt the legislative process on policy issues of importance to them, using the MEPs they will have in key committee positions or issuing large amounts of amendments to legislative proposals. Importantly, these dynamics may also impact on the centre of gravity of the EPP and make it more difficult for the S&D and ALDE to be in a stable coalition with the EPP beyond the initial appointment of the Commission. Likewise, the need for increased consultation among political groups to form broader agreements on legislative files could make the negotiating process more time-consuming and increase the likelihood of watered-down proposals to facilitate reaching a common understanding.

Figure 7 – European parties’ stances on immigration and left-right spectrum

To conclude, our analysis suggests that the next European Parliament will be more fragmented independently of Brexit. Out of arithmetic necessity, parties’ positioning on European integration is likely to be the key in forming the majority needed for the appointment of the next European Commission. This majority will however be weaker. It will also be heterogeneous in terms of positioning on the left-right spectrum, societal values and salient issues. This in turn could lead to less ambitious legislative proposals and alternative ad hoc majorities being formed on individual pieces of legislation. The heterogeneity of the coalition underpinning the new European Commission and its weakness in the European Parliament could moreover impact the inter-institutional balance of power to the benefit of the European Council and the intergovernmental approach to European policymaking, at the expenses of the Commission, the European Parliament and the Community method.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the institutions with which they are affiliated, the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. Image by Marco Verch: original photo and the license.

Thierry Chopin is the author of several books and articles on European integration. He holds a PhD in Political Science from the School for Advanced Studies in Social Sciences (EHESS). He is Professor of Political Science at the Catholic University of Lille (ESPOL, European School of Political and Social Science) and Visiting Professor at the College of Europe (Bruges). He is special advisor at the Jacques Delors Institute.

Nicolò Fraccaroli is a PhD candidate in Economics at the University of Rome Tor Vergata. He holds a MSc in Political Economy of Europe from the London School of Economics and a bachelor in Political Science from LUISS Guido Carli (Rome). He is co-author with Robert Skidelsky of the book Austerity vs Stimulus. The Political Future of Economic Recovery (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017).

Nils Hernborg is currently a Master student in International Economic Policy at Paris School of International Affairs, Sciences Po. Prior to pursuing his master, he worked as data analyst in the fintech industry. He also holds a BSc in Political Economy from King’s College London.

Jean-Francois Jamet is the author of several books and articles on European integration and the Economic and Monetary Union. He studied Economics at the Ecole Normale Supérieure (Paris School of Economics) and Harvard University, and Political Science at Sciences Po. He has worked for the World Bank and the European Commission.