Thirty years ago today, on June 4 1989, Communism ended in Poland. In this post, Jim Bjork (KCL) argues that what made the end of authoritarian rule in Poland a success story was not an expression of unitary national will but rather an ability to navigate conflicts and accommodate different interests over time. Reflection on the power and the limits of plebiscitary approaches to elections is more relevant than ever as Britain grapples with the results of the Brexit vote. People use their ballots to make statements about who they are and the kind of community with which they identify. But the result of aggregating such statements can never be a stable crystallization of a communal identity, whether national or European. The lesson from Poland, 30 years on, is that the art of democracy lies in recognizing and navigating the persistence of differences, he concludes.

Thirty years ago today, on June 4 1989, Communism ended in Poland. In this post, Jim Bjork (KCL) argues that what made the end of authoritarian rule in Poland a success story was not an expression of unitary national will but rather an ability to navigate conflicts and accommodate different interests over time. Reflection on the power and the limits of plebiscitary approaches to elections is more relevant than ever as Britain grapples with the results of the Brexit vote. People use their ballots to make statements about who they are and the kind of community with which they identify. But the result of aggregating such statements can never be a stable crystallization of a communal identity, whether national or European. The lesson from Poland, 30 years on, is that the art of democracy lies in recognizing and navigating the persistence of differences, he concludes.

On June 4 1989 Polish voters went to the polls to elect new members to the national legislature. The election was designed to produce a managed, incremental modification of the Communist regime’s four-decade-long rule. Only a third of seats in the lower house (the Sejm) were contested, and the newly revived upper house (the Senate), where all seats were subject to open competition, had very limited power. As resilient as the Solidarity opposition movement had proved during the previous decade, neither the regime nor the Solidarity leadership believed the movement had enough organizational muscle to achieve more than piecemeal electoral victories.

What followed was a landslide. Only a handful of regime-backed candidates even won enough votes to make it to second-round run-off elections. By the end of that second round, Solidarity had won 99 of 100 Senate seats and all of the 161 seats in the Sejm that had been subject to open, competitive elections. Over the following weeks, representatives affiliated with what were meant to be docile satellite parties of the Communist party indicated that they were now ready to cast their lot with Solidarity. The formation of a government led by a non-Communist, an outcome originally meant to be precluded by parliamentary arithmetic, quickly came to be required by parliamentary arithmetic. As Solidarity activist Tadeusz Mazowiecki assumed the role of prime minister, a template for regime change suddenly came into view. Within the following few months, every Warsaw Pact regime outside of the Soviet Union had been replaced.

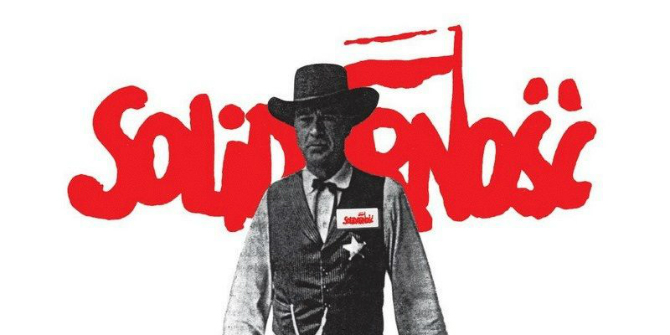

This election was, in short, the most plausible single tipping point in the chain of events that we cumulatively characterize as the “fall of Communism.” The description of June 4th as Poland’s ‘High Noon’, captured in the campaign’s most famous poster, featuring a ballot-toting Gary Cooper, seemed incredibly apt in the months following the outcome. And yet today, the Polish election only rarely figures as a pivotal plot point in accounts of the collapse of the Soviet bloc. When, for example, first-year History undergraduates in the UK are asked to explain the fall of Communism, their narratives tend to involve two elements: 1) an East European population perennially hostile to Communism and exhibiting increasingly acute economic discontent by the 1970s and 1980s; and 2) a Soviet regime that eventually, with the rise to power of Mikhail Gorbachev, tired of using armed force to suppress this discontent. Popular discontent was expressed in a variety of ways, including spectacular outbreaks of mass protest, such as in Hungary and Poland in 1956, Czechoslovakia in 1968, and Poland again in 1970, 1976, and 1980. But even in the long stretches across most of the Soviet bloc when there were no large-scale protests and dissident activity was limited to a small minority, a silent majority ready to repudiate Communism could be assumed. In this interpretation, the decision by the Polish regime to allow a largely free election, and the decision by Moscow to refrain from intervention, led with absolute predictability to the collapse of the system. The election itself simply confirmed what everyone already knew about what everyone had long felt.

The relegation of the June 4 elections to anticlimax tells us a lot about common understandings of how the Soviet bloc worked. It also says a lot about our ambivalence toward the role of elections in the functioning of democracies. Election results are often most satisfying when they are emphatic and lopsided, either as affirmations or repudiations. They provide reassurance about the cohesion of the community. But it is precisely because such elections are both so high stakes and ostensibly so predictable—what would it mean for a community to decide it is not who it thought it was?—that this plebiscitary mode of thinking about voting can easily become a reason not to hold elections at all.

But there is an alternative to celebrating—and, at the same time, effectively forgetting—the elections of June 4 1989 as a plebiscitary confirmation of Poland’s permanent opposition to Communism. These elections provide a more interesting and fruitful example of practising democracy if seen as a genuine , suspenseful event, shaped by the evolving decisions of Solidarity activists, ordinary voters, and regime officials both before and after the balloting. The widespread anticipation of a mixed and messy result was not, after all, simply due to a dearth of sound polling data. It instead reflected an understanding that any rallying behind a single opposition group could only be partial, contingent and fragile. The dramatic headline results—Solidarity sweeping almost every legislative race—only temporarily obscured the fact that millions of Poles had voted against Solidarity, and millions had stayed home. Four years later, a reformed successor of the Communist party would go on to win the next round of parliamentary elections. Four years after that, a loose coalition made up of some post-Communist and some post-Solidarity supporters produced a narrow majority ratifying a new Polish constitution, in the teeth of opposition from other former Solidarity activists. What made the end of Communism in Poland a success story overall (despite many caveats) was not an expression of unitary national will that swept all before it but rather an ability to navigate conflicts and accommodate different interests over time.

Reflection on both the power and the limits of plebiscitary approaches to elections is more necessary than ever today. We have certainly seen, in the British referendum of 2016 but also in the recent European parliament elections, the mobilizing potential of either/or messages. Voters, understandably and unavoidably, use their ballots to make statements about who they are and the kind of community with which they identify. But the result of aggregating such statements can never be a stable crystallization of a communal identity, whether national or European. The art of democracy is in recognizing and navigating the persistence of differences, even, or perhaps especially, when it is plausible to imagine ‘the people’ speaking in one voice.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. Image by Tomasz Sarnecki (ipn.gov.pl).

Dr Jim Bjork is a Reader in Modern European History at King’s College London.