There has been a tendency in British public discourse since the 2016 referendum on EU membership to identify the residents of Northern England as the principal “culprits” of the Brexit vote, writes Craig Berry (Manchester Metropolitan University). In truth, the North has been deliberately subjugated to the dominant economy of the south-east.

There has been a tendency in British public discourse since the 2016 referendum on EU membership to identify the residents of Northern England as the principal “culprits” of the Brexit vote, writes Craig Berry (Manchester Metropolitan University). In truth, the North has been deliberately subjugated to the dominant economy of the south-east.

Given that, in a direct, immediate sense, it appears that the North will be more negatively affected than most other parts of the UK (or certainly England) by departure from the EU’s economic zone, this narrative has fed a sense that Northerners have acted both selfishly and foolishly. The North, so the argument goes, has dragged the UK out of the EU against the wishes of most of its constituent regions and nations, and, in doing so, acted in contradiction of its own economic interests.

The Brexit vote has been interpreted in line with historical depictions of Northerners as unsophisticated and downtrodden, with the occasional bout of truculence. The North voted to leave the EU because it has been “left behind” by more prosperous metropolitan areas.

Co-opting the North

Nevertheless, the notion of the North as strongly pro-Brexit has been exploited by political elites, on both left and right.

The right-wing populism most closely associated with Nigel Farage and the Conservative Party’s ascendant ERG faction consistently claims support of “ordinary folk”. That enables them to add a flavour of anti-establishment sentiment to their elite-led and ultra-neoliberal pro-Brexit agenda.

Paradoxically, this notion is also central to the left-wing Brexit or “Lexit” imaginary, long upheld by Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn and some of his most loyal supporters. The notion that the North – a so-called Labour “heartland” – is strongly supportive of Leave is convenient to this perspective. But the main advocates of the Lexit argument are, like Corbyn, products of London-centred political communities. The ascendancy of this perspective on the left explains Labour’s timidity over supporting a second referendum.

The North’s Brexit preferences

But if you take a good look at the results of the 2016 referendum, it dramatically challenges the notion that support for Brexit is centred in the North. Turnout is lower in the region and the population smaller.

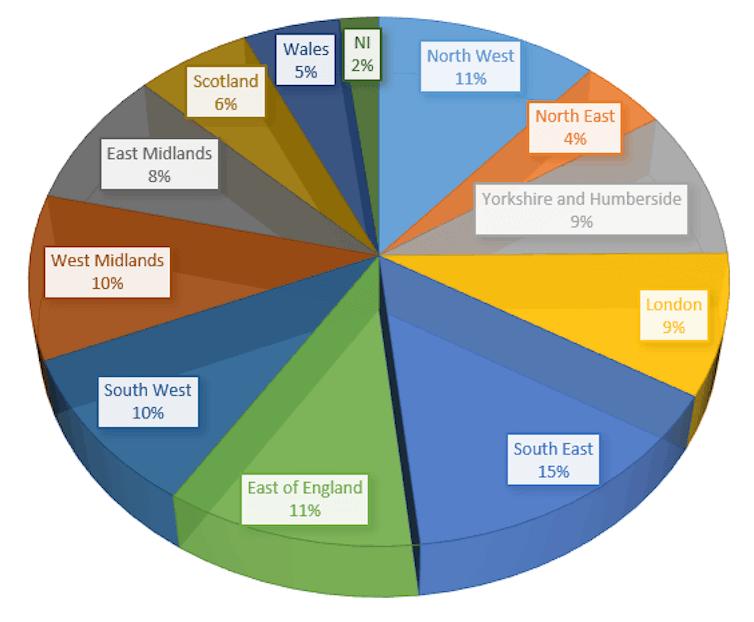

In fact, the South East had the highest percentage of Leave voters. This region accounted for 15% of the national Leave vote. The North West (the North’s most populous region) and East of England both delivered around 11%, closely followed by the South West and West Midlands (both 10%). There were as many Leave voters in London as Yorkshire (both 9%). The North East actually delivered fewer Leave votes (4%) than even Scotland (6%).

Figure 1: Regional composition of national Leave vote, 2016 referendum

Treating the three Northern regions, and London and the wider South East, as two mega-regions is also informative. While there were many more Remain voters in London and the South East in 2016 (around 4.7m, or 29% of the national Remain vote, versus 3.4m in the North, representing 21.1% of the national Remain vote), the differences in terms of the Leave vote are far less significant. There were 4.3m Leave voters in the North, versus 4.1m in London and the South East. This represents 24.9% and 23.4% of the national Leave vote, respectively.

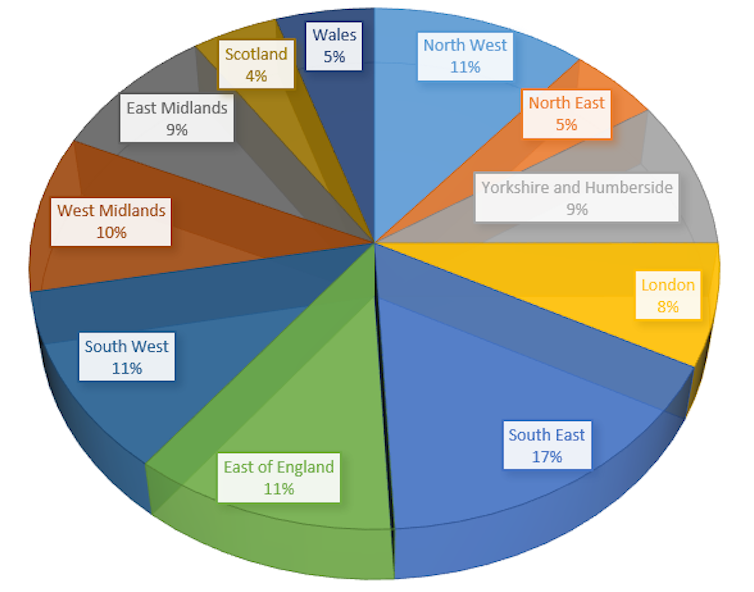

My report for Future Economies, Brexit and the North: Not Our Problem, applies the same approach to the 2019 European election to determine regional support for either a “no-deal” Brexit, or the revocation of Article 50 (via a second referendum). Including only votes for parties explicitly promising (at the time of the election) to leave the EU without a withdrawal agreement, or explicitly promising revocation or a second referendum, a similar pattern emerges: the South East (15%), South West (11%), East of England (11%) and North West (11%) are the main regional drivers of the national “no-deal” vote.

Figure 2: Regional composition of national ‘no deal’ vote, 2019 EU election

While there were many more revocation/second referendum voters in London and the South East in 2019 (around 2.1m, or 18% of the national revocation/second referendum vote, versus 1.1m in the North, representing 10% of the national vote), the differences in terms of the no-deal vote are far less significant. There were just under 1.5m no-deal voters in the North, versus just over 1.4m in London and the South East – this represents 25% and 24% of the national no-deal vote, respectively.

The need for nuance

As such, the North generally supported Leave over Remain in 2016, and slightly more people expressed support for no deal over revocation and/or a second referendum in 2019. Yet not decisively so. This is not to suggest that there is not strong support for Brexit in some parts of the North – or indeed that the 2016 result should not be respected.

But we must avoid an absolutist interpretation of the Brexit vote – especially one that invokes a simplistic account of support for Brexit in the “left behind” North. Above all, the recent European election shows that support for a no-deal Brexit is very limited in the North (as everywhere else, with the partial exception of the South East).

We should see the North not as simply “left behind”, but rather deliberately subjugated, in the sense that centralised political structures and a finance-centred growth model inhibit economic development in the North. Many see leaving the EU as part of the solution, but many instead recognise an ultra-neoliberal Brexit agenda, anchored in the South East, as more of the same – neglecting economic activity in the North while pursuing a trade agenda which prioritises the globalised industries of London and the South East.

Better representation for the North in national debates (and policy-making processes) is an end in itself, but it might also help us to finally break the Brexit impasse and arrive at a consensual approach to withdrawal.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor LSE. It first appeared at The Conversation and is republished under a Creative Commons licence.

Craig Berry is a Reader in Political Economy at Manchester Metropolitan University.

1 Comments