What do the children of the EU migrants who moved to Britain think about politics? Daniela Sime (University of Strathclyde) says that although many do not yet have the right to vote in general elections because of their non-British nationality, politicians risk alienating this bloc of future voters unless they reach out to them now.

What do the children of the EU migrants who moved to Britain think about politics? Daniela Sime (University of Strathclyde) says that although many do not yet have the right to vote in general elections because of their non-British nationality, politicians risk alienating this bloc of future voters unless they reach out to them now.

Of the 3.6 million non-British EU nationals living in the UK, about 600,000 are children and young people who moved to Britain with their parents or were born here. Although most of them, like their parents, did not have a right to vote in the EU referendum in 2016, their future will dramatically change post-Brexit, no matter which of the scenarios we end up with. Although non-British nationals could not vote in the EU referendum, it is becoming increasingly clear that the subsequent debate has engaged EU nationals with politics and party policies more than ever before.

In an ESRC-funded study called Here to Stay? which we carried out with 12-18 year-olds born in central and Eastern Europe and living in the UK for at least three years, we found that the referendum result and ongoing uncertainty had preoccupied young people. In a survey we carried out of over 1,100 young people, drawing on a self-selected sample from across the UK, the majority said they felt ‘uncertain’ (56%), ‘worried’ (54%), and ‘scared’ (27%).

As we reported in a Guardian article, three-quarters of respondents also said they had experienced more racism, prejudice-based bullying and xenophobic incidents since the referendum. These incidents ranged from everyday racism disguised as banter (‘you are Putin’s friend, Russian terrorist’), to physical attacks and families having swastikas drawn on their properties. Overall, 31% of respondents reported that they sometimes felt unsafe in their local community and 38% thought that people living in the community were either prejudiced or very prejudiced against Eastern Europeans. Young people said that they tended not to report incidents in the belief that their experiences would not be taken seriously by the police or teachers, and that they did not think politicians cared about the situation of EU nationals in Britain.

On a question on interest in politics, over half of survey respondents (51%) reported that they were ‘quite interested’ or ‘very interested’ in politics. These are slightly higher rates than those reported by other polls among the general populations. A YouGov poll from 2017 found that 39% of young respondents (aged 18-24) saying they were certain to vote at the next polls. About the same percentage of 18-24 olds (36%) had voted in the referendum, which allowed Brexit campaigners to say that young people cannot claim they were betrayed by older pro-Brexit voters, as almost two-thirds did not bother to vote. Similarly, only 26% of young people under the age of 30 said they had an interest in voting in the US compared to 86% of people over 65, while in Europe, a 2019 poll carried out by the European Council on Foreign Relations and YouGov shows that young voters – sometimes called Generation Z (those aged 18-24) and millennials (those aged 25-34) – are less likely to vote than other groups.

So given the apparent lower rates of political interest among the younger generation, should we care about their political preference and voting intentions? I argue there are three reasons why parties should aim to appeal to young voters, including the EU nationals we surveyed.

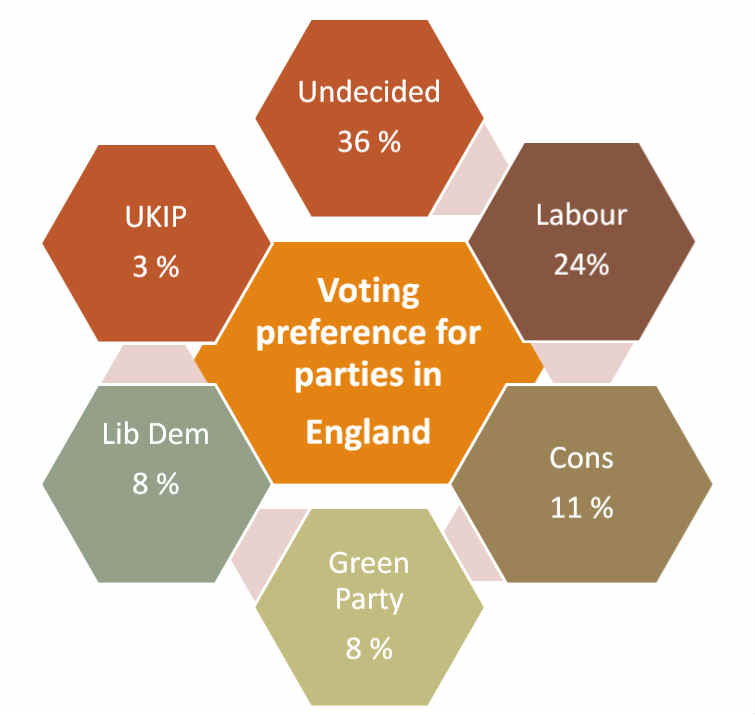

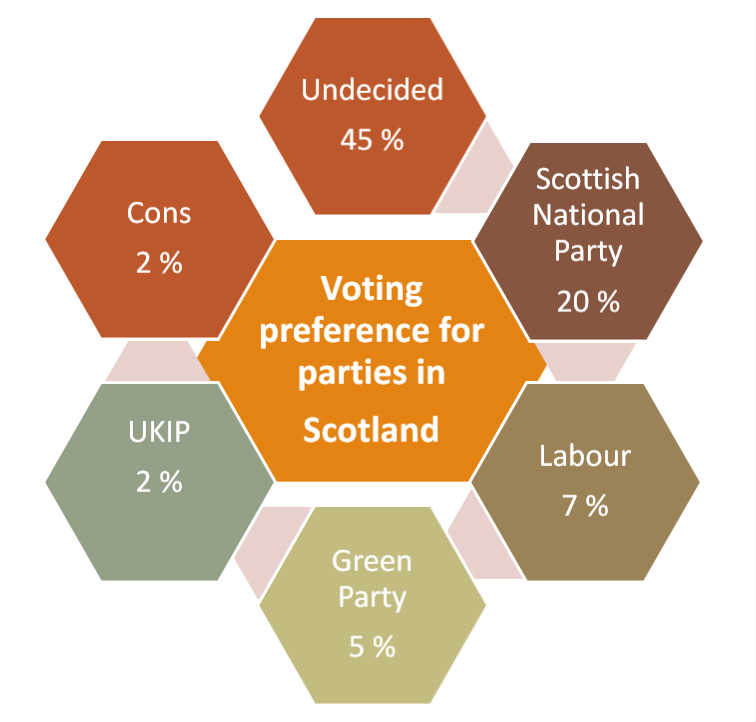

The first is that many of the young people seem to have clear political allegiances from early on (i.e. age 12 and younger). Issues such as inequalities, migrant and refugee rights and climate change are likely to interest many of the new generation and make them likely to vote and have a say in their countries’ future. Similarly, the older young people get, the more likely they are to become interested in political parties and what they stand for. They are also more likely to vote. In our sample, young people aged 12-15 were more likely to say they wouldn’t vote (13%) or didn’t know who they would vote for (47%) than 16-18-year-olds (10% and 35%, respectively). Young EU nationals living in England were more likely to say they were interested in politics that those living in Scotland. In addition, respondents in Scotland were more likely to say that they wouldn’t vote (18%) than those in England (9%). The voting preferences for the respondents who said they would vote are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Figures 1 and 2. Young people’s voting intentions (England n=718; Scotland n=191)

The second reason to include young voters in future political debates and election campaigns is the fact that a significant number are ‘undecided’ voters in our sample. One in three in England and almost one in two in Scotland said they were ‘undecided’ and wanted more information on what parties stood for. This also makes young people available to drift to political parties that may make the effort to engage younger voters or promise quick fixes to existing social problems, such as far-right parties (see Marine Le Pen’s appointment of a 23 year-old as head of her party’s list for the European elections, or the Brexit Party’s attempts to recruit young members).

For young people in our sample who were mostly citizens of other EU countries, the right to vote in elections was denied by their lack of British citizenship, even if they had lived in the UK for many years. As one of our participants, Jakub (Polish national, 17) explained his general frustration with the lack of voting rights and how his sense of belonging was altered by limited citizenship rights:

Up until Brexit, I felt like I belonged, but then the vote came as a wake-up call. I suddenly realised that in the eyes of the law, I’m inherently different and my rights are not set in stone. Then came the realisation that since I’m not a British national, I don’t have the right to vote and hence politicians don’t care about what I have to say. Really, it’s a bit sad that despite feeling British and being completely integrated, I am denied this.

Only 8% of the young people in our sample said they had British or dual nationality. For many, the threat to their status in the UK post-Brexit, in addition to lack of voting rights, was a catalyst to consider applying for British citizenship. When we discussed everyday citizenship in focus groups, young people tended to relate the concept of ‘citizenship’ to nationality or the process of securing British nationality. While many young people said that they wanted to secure citizenship, in light of the uncertainty surrounding their status in the event of Brexit, there was concern about their families’ ability to cover the high cost of securing British citizenship, which is currently over £1,300. However, if a significant number of EU nationals do secure citizenship, they will become a meaningful part of the electorate. As many of them are watching the ongoing Brexit negotiations closely, their political affiliations are likely to be shaped by the support they are currently receiving from political parties in securing their rights.

The final reason to consider young people’s voting intentions is the potential they have to re-energise the political arena with new forms of engagement and civic activism, including through social media and online platforms. Their involvement would also help address the issue of limited diversity among our political representatives, on aspects such as gender, ethnicity, class and migrant background. The current youth generation have grown up under the politics of austerity and the threat of global terrorism, feeling unrepresented by a detached elite and morally compromised and sometimes corrupt political class. Passionate about issues such as climate change, equality and fairness, and technological innovation, there are new opportunities to build on young people’s enthusiasm for a better future and a safer and fairer world. In our study, young people who thought their family were ‘badly off’ were more likely to say they were interested in politics, which shows how experiences of adversity can shape young people’s desire to see things change.

It is time political parties engaged with younger demographics and started taking their concerns more seriously; equally, during political crisis, schools and educators need to do more to engage young people in debates about politics and what parties stand for. Parties should produce manifestos that include the issues young people care about, and address future voters directly and from a younger age. Unless young people feel their concerns are being acknowledged and addressed by political parties and governments, they may find alternative forms of activism away from the political arena – as we have seen recently through the climate change movement initiated by Greta Thunberg – or they may decide to punish politicians through their future votes, once they gain them.

About the survey

The survey took place between October 2016 and April 2017. In total, 1120 young people completed the survey, and most were aged 16-18 (68%), while 32% of respondents were aged 12-15. Over half of the respondents were Polish (56%), followed by Romanian (10%) and Lithuanian (9%) nationals. The other 25% of our respondents were originally born in other EU and non-EU countries to Eastern European parents. Most respondents lived in England (71%) and some in Scotland (19%), while 10% did not give their location.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor LSE.

Daniela Sime is a Reader in Youth and Social Justice Research in the School of Social Work & Social Policy at the University of Strathclyde.