Economic performance varies widely between different places in the UK, writes Henry G. Overman (LSE). There is a broad North-South pattern, but also substantial variation within those areas. In some measures, the performance gap has widened since the financial crisis. Austerity too reduced redistribution and so it is partly responsible for the recent widening of spatial disparities. Conseqently, the Brexit vote, for example, was highly uneven with some places more likely to vote Leave and others more likely to vote Remain. Policy, however, needs to make sure that people in disadvantaged communities can access the opportunities generated, which will require substantial intervention across a wide range of policy areas.

Economic performance varies widely between the towns, cities and regions of the UK. On some measures, this variation has widened since the financial crisis. These disparities have already proved to be a key theme in the run-up to the 2019 general election. Spatial disparities are important because local social and economic conditions affect individual outcomes. For example, there are substantial differences in social mobility at the local level: where you grow up makes a difference to how much your family background affects your life chances. Spatial disparities also reflect individual inequality. For example, if individual inequality increases and poorer families are concentrated in particular areas, then spatial disparities will also increase.

The link between individual and spatial disparities is complicated by the fact that people can move around. This matters for thinking about what spatial disparities can tell us about important policy issues. For example, the geography of the Brexit vote was highly uneven with some places more likely to vote Leave and others more likely to vote Remain. One explanation is that the Leave vote reflects the ‘revenge’ of ‘left-behind’ places – that is, it is a story not about individuals, but about shared anger by those living in places left behind by technological change and globalisation. The alternative is to think of this as a story about individuals, left behind by the same forces, and where they live.

The first way of thinking about this appears to be driving the current policy response. But the second is perhaps a more useful way of understanding why wealthy Sevenoaks and struggling Sunderland both voted Leave. Different kinds of people, with very different concerns about the European Union, living in different places – but agreeing on the same solution. The other reason why individual mobility matters is because it means that policies targeted at specific places don’t necessarily end up benefiting the people that we hoped to help. For example, transport improvements in a poorer area don’t necessarily end up benefiting poorer families if those improvements then lead to higher rents and house prices that see them priced out of the neighbourhood.

Taken together, these two complications – the need to distinguish between people and place; and the fact that people move between places – mean that it is important for us to understand what is causing spatial disparities and to think carefully about who will benefit from the different policies proposed to address these disparities.

Image by Cnbrb, made available under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

Disparities in the UK: it’s more than just a North-South divide

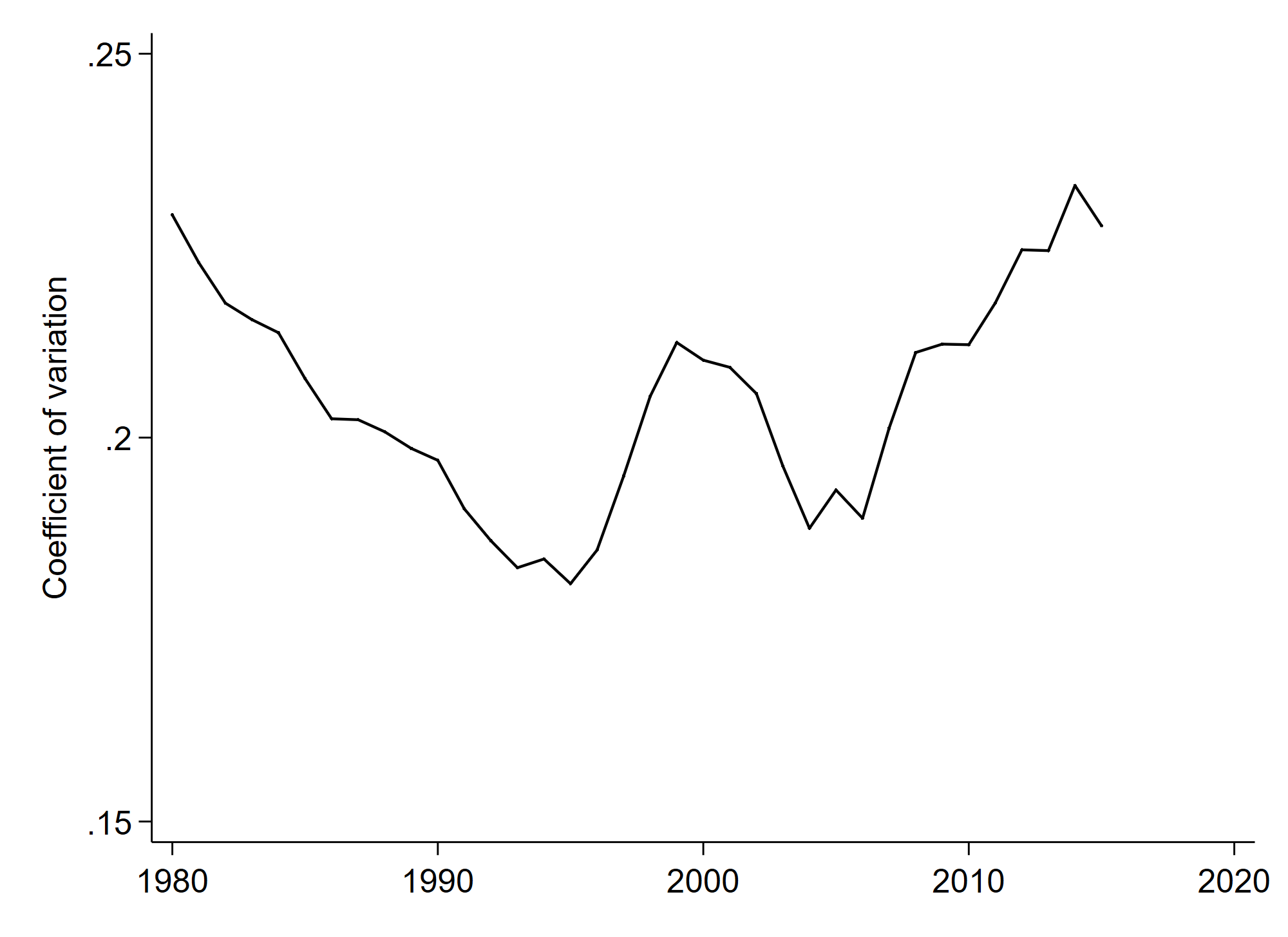

There is a broad North-South pattern to spatial disparities in the UK. Cities Outlook is the most useful source of detailed data on the economic performance of UK cities. The 2019 report shows a very clear geography in terms of both output per worker and employment, with cities in the Greater South East performing better. Eight of the 10 cities with the highest unemployment (claimant count) are in the North of England or Scotland. There is also substantial variation within those broad areas: some northern cities (such as Manchester) are doing relatively well and some southern cities (such as Ipswich) are doing relatively badly. Despite many policy initiatives by the current and previous governments, these disparities remain large and persistent. Indeed, these disparities have widened since the global financial crisis. Figure 1 shows a standard measure of the extent of spatial disparities (the coefficient of variation) calculated for the (NUT2) regions of the UK from 1980 to 2015, the last date for which we have data. Disparities fell between 1980 and the mid-1990s, increased in the early days of the Labour government before falling again. The increase in disparities since the recession has returned us to roughly the level of the 1980s.

Figure 1: Spatial inequality in the UK

Source: Author’s own calculations based on Eurostat data for NUTS2 regions of the UK

What are the economic forces polarising the UK?

Better educated workers are concentrated

According to Eurostat’s latest figures, in 2018, around 65% of inner London residents had tertiary education, the highest percentage in Europe. This was up from around 54% in 2010. In contrast, the proportion of residents with tertiary education in Greater Manchester was around 39% in 2018, up from 31% in 2010. There is also a growing wage premium for graduates compared with people without degrees. Numbers reported by Elliot Major and Machin (2018) show that in 1980, male graduates earned, on average, 46% more than their non-graduate counterparts. In 2017, this earnings uplift was 66%. Given a strong and growing concentration of more educated workers and a large and increasing wage premium for graduates, it is not surprising that the spatial distribution of higher skilled workers explains up to 90% of area-level disparities in wages in the UK (Gibbons et al, 2013).

Figure 2: Shares of population with tertiary education

Bigger cities make firms and people more productive

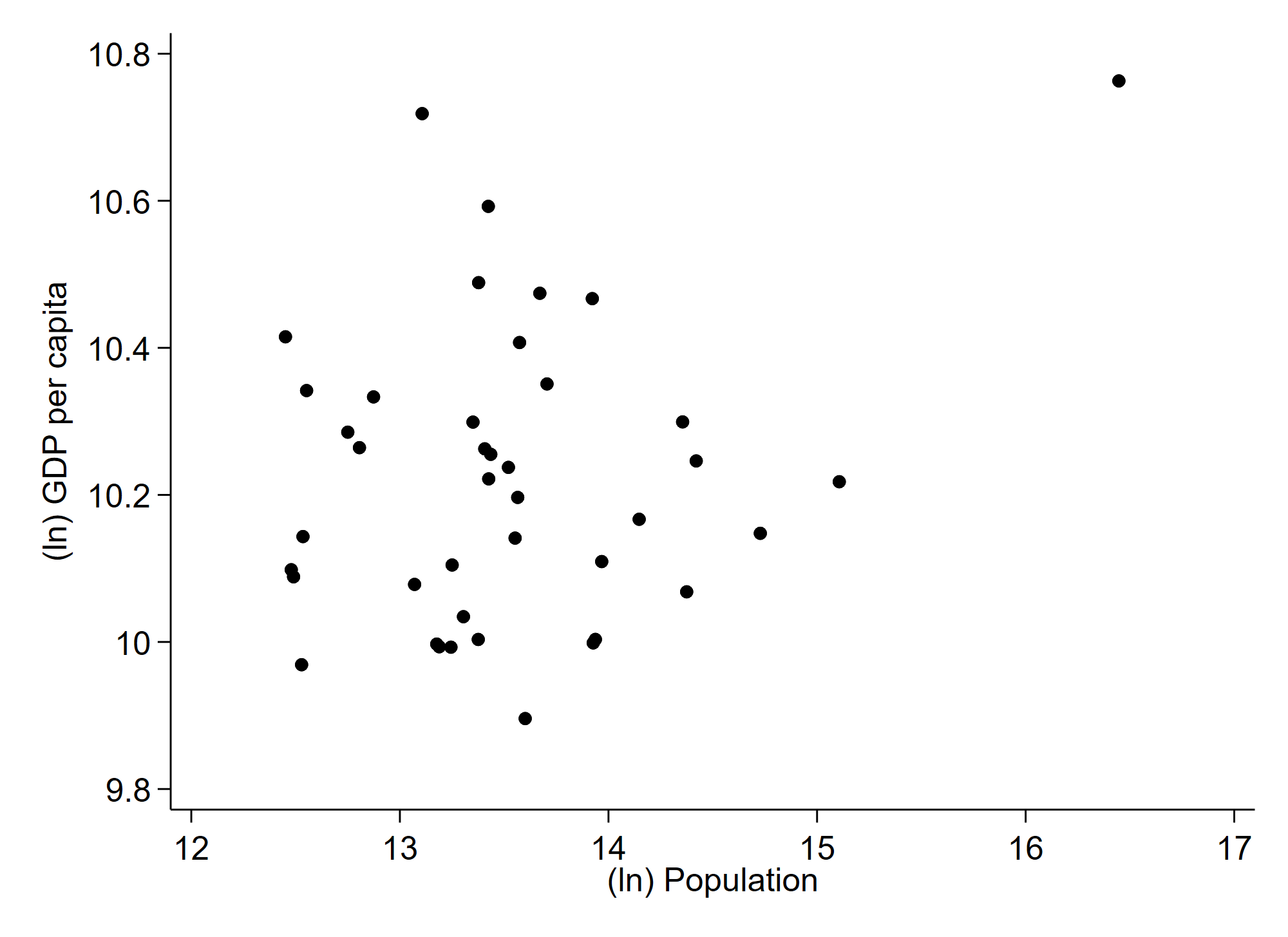

There is a great deal of empirical evidence of the ‘agglomeration economies’ that underpin the relationship between a city’s size and the productivity of its inhabitants. Graham and Gibbons (2018) summarise results from 47 studies estimating these agglomeration economies, 12 of which are from the UK. The consensus estimate suggests that once we allow for the unequal spatial distribution of higher-skilled workers, the elasticity of productivity with respect to size is around 0.02 to 0.03. This means that doubling city size increases people’s productivity by around 2-3%. While these productivity effects are important, when it comes to GDP per capita, they can easily be swamped by spatial disparities in the share of skilled workers. This happens in the UK where (if we exclude London) the overall relationship between city size and GDP per capita isn’t very strong – as Figure 3 shows. Our cities still benefit from agglomeration economies – someone with a degree moving from Blackpool to Manchester would be more productive – but this isn’t enough to encourage the sorting of highly skilled workers into some of our bigger cities outside London.

Figure 3: GDP per capita against city size for UK MSA

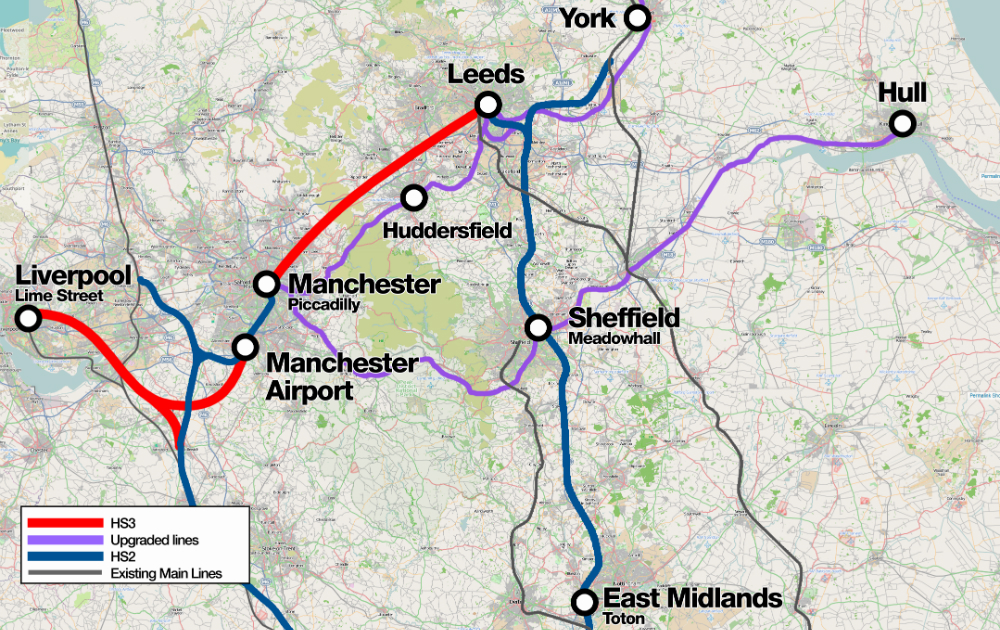

Underinvestment in the North

Because London and the South East are rich and our tax system is progressive, there is a lot of redistribution from the South to the North. But on some measures, London receives a disproportionate share of investment in infrastructure. A more equal distribution of infrastructure investment would slow growth in London. Whether it would increase growth elsewhere would depend on how the money was spent because the economic returns to infrastructure vary a lot across places. The overall effect on regional inequalities would be limited since relative to the concentration of skilled workers, differences in infrastructure play a relatively small role in driving long-term disparities. The only way for infrastructure to have a big effect on spatial disparities is if it leads to the relocation of large numbers of skilled workers across the UK, away from London.

The financial crisis and austerity

London and the South East were initially hard hit by the recession, but they have recovered more quickly. Adjustment elsewhere has been slower and, as a result, spatial disparities have widened. Local government in England has borne the biggest burden of austerity and cities in the North of England have been much harder hit than those elsewhere (Cities Outlook 2019 provides more detail). Given that austerity reduced redistribution, it is partly responsible for widening disparities.[3] The resulting cuts to public services may mean that austerity hindered adjustment to the financial crisis and that the adverse effects on disparities could persist in the medium to long run.

Improving economic performance outside the capital

Rather than focusing on London’s dominance, we should ask why other cities and towns do not offer similar economic opportunities and what can be done about it? Given what we know about the economic forces driving polarisation, there are two key questions:

(1) In which places could greater investment and other government support be used to increase productivity and help create jobs?

(2) How do we make sure that people can access these opportunities?

Evidence suggests that around 50% of people only ever work while living in the local labour market where they were born (Bosquet and Overman, 2019). This suggests that the policy response needs to be realistic about how far people are willing to move for work, particularly for less educated workers (the figure rises to 60% for those without a degree). Having ‘everyone’ move to London and the South East is not economically feasible, nor socially or politically acceptable. The same is true for the other extreme: achieving a level playing field where productivity is equalized, and jobs are generated ‘everywhere’. We need to be realistic about the market forces at work. Equal outcomes across places requires places to have similar skill composition and to be of similar sizes. As with the previous strategy, this is not economically feasible, nor socially or politically acceptable.

London’s strong economic performance plays a large part in explaining widening disparities. Providing an effective counter-balance to London may require some investment to be more spatially focused – for example, by identifying a number of places, spread across the UK, that are doing relatively well and focusing infrastructure investment on achieving productivity and jobs growth in those areas.

‘Left-behind’ places

An effective policy response will require increased investment (LSE Growth Commission, 2013) and the reversal of austerity. ‘Left-behind’ places have high proportions of vulnerable people with complex needs and low levels of economic activity. This compounds their problems, as long-term unemployment, poverty, mental illness and poor health often go hand-in-hand. CEP research suggests that small tinkering and minor tweaks of existing policies will not be enough to tackle the multiple barriers to social mobility faced in these places. It is also important to be clear that spending in left-behind places does not always need to be justified based on economic performance. There are important public good arguments that could justify increased expenditure across a wide range of policy areas. For example, it is possible to argue for subsidising rural broadband as a public good while recognising that its economic impacts are likely to be limited.

Distributional arguments can also be used to support intervention. For example, reversing austerity cuts to welfare benefits would disproportionately benefit areas with high concentrations of disadvantaged households. But it is important to be realistic about the likely economic impact of these policies so that we properly consider sustainable sources of government revenue to fund this increased public expenditure.

Conclusion

Spatial disparities in the UK are profound and persistent. Improving economic performance and helping to tackle the problems of left-behind places are both important policy objectives. Addressing these challenges requires a new approach to policy, one that allows for different responses in different places. Such variation makes many people nervous. But it is important to remember that we should care more about the effect of policies on people than on places. Policies should be judged on the extent to which they improve individual opportunities and on who benefits, rather than whether they narrow the gap between particular places.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE. It is an edited extract from a Centre for Economic Performance (CEP) briefing.