Do countries do well by doing good? More precisely, does a country admired by others reap any benefit? My research indicates that the answers to these questions is “yes” and “yes”. I have taken advantage of a quantitative measure of soft power to show that a country sells more exports to nations that perceive it to be a force for good, holding other factors constant. These higher exports can be viewed as a carrot that rewards behaviour admired by others, symmetric to the sticks more commonly used in international commerce. My results show that global behaviour perceived to be better/worse has a material effect on exports.

Joseph Nye first introduced soft power — a country’s ability to attract or persuade others to do its bidding, in contrast with “hard power” or force. Europeans pride themselves on their soft power; Americans tend to think highly of their hard power. Whereas hard power grows out of a country’s military or economic might, soft power arises from the attractiveness of its culture, political ideals, and policies, and it is by no means under government control. Nye considers hard power to stem from a country’s population, resources, economic and military strength and the like. By way of contrast, “Soft power is … the ability to attract, [since] attraction often leads to acquiescence … soft power uses a different type of currency (not force, not money) to engender cooperation – an attraction to shared values …” .

I estimate that a one percent net increase in soft power raises exports by around .8 percent, holding other things constant. Being perceived as a force for good has a direct economic pay-off. Succinctly, winning hearts and minds leads to wining sales. I find this effect to be relatively (but not completely) insensitive to a variety of robustness checks. I am interested in whether importers change their observable behaviour when they perceive an exporter to be behaving better or worse in the world. My default measure is developed for the BBC World Service through its partnership with the international polling firm GlobeScan and the Program on International Policy Attitudes (PIPA) at the University of Maryland.

The research:

Participants in a large number of countries (33 in 2006) are asked about their views on a smaller number of countries (8 in 2006, as well as “Europe”). The precise question wording in English is: “Please tell if you think each of the following are having a mainly positive or mainly negative influence in the world:

| READ AND ROTATE | |

|---|---|

| 1. China | |

| 01 | Mainly positive |

| 02 | Mainly negative |

| VOLUNTEERS DO NOT READ | |

| 03 | Depends |

| 04 | Neither, no difference |

| 99 DK/NA | |

| 1 | Britain |

| 2 | Russia |

| 3 | France |

| 4 | The United States |

| 5 | Europe |

| 6 | India |

| 7 | Japan |

| 8 | Iran |

These surveys have been conducted annually since 2006. Participants in 46 countries have been asked about the influence of a total of 17 countries over the years. All in, there are 2730 observations, with two variables concerning the global influence of one country as perceived by others: the percentages answering “mainly positive” and “mainly negative” (these do not usually sum to 100%). I construct a third variable by subtracting the negative from the positive perceptions; the difference is a measure of net perceived influence.

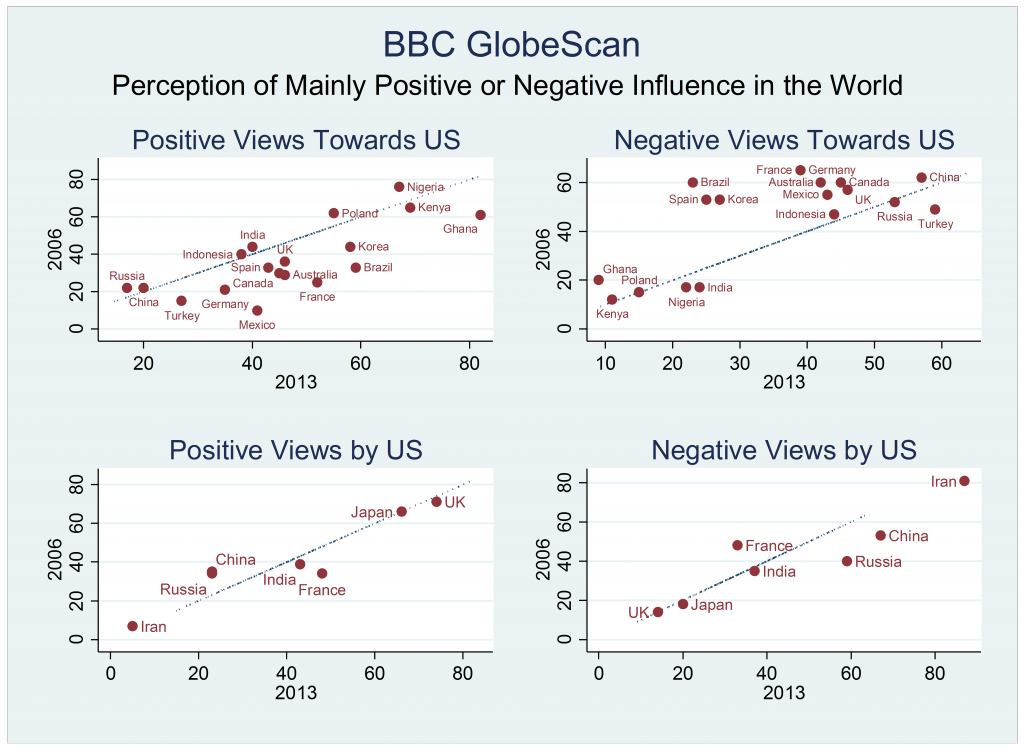

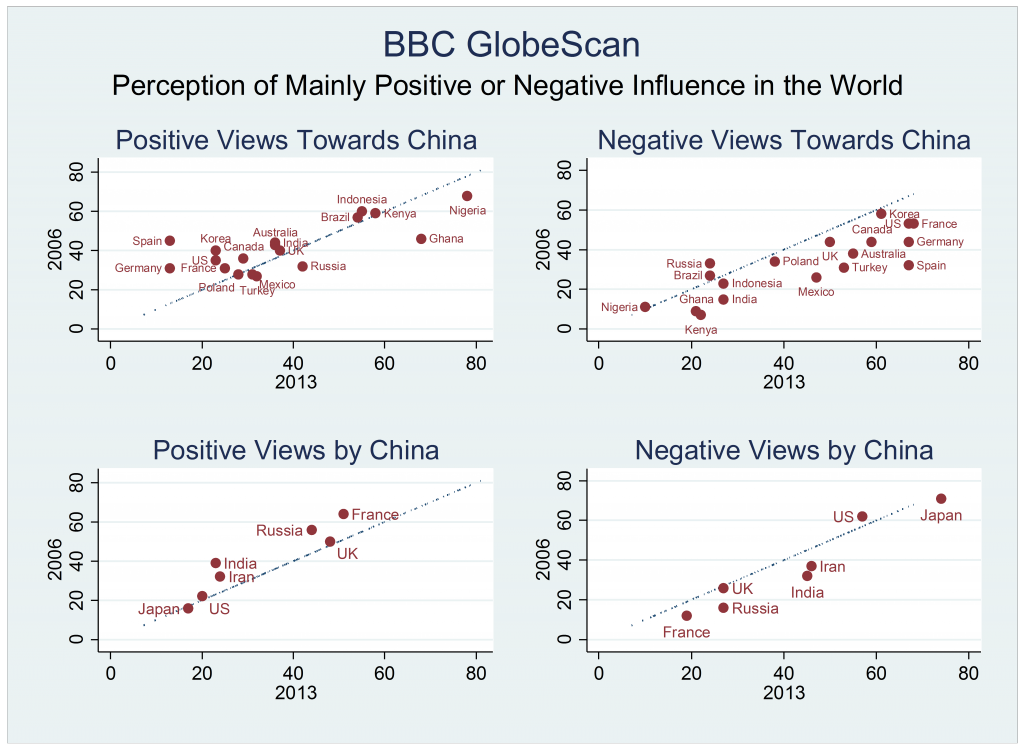

Figure 1 provides some concrete examples. Consider the top-left graph in Figure 1. This shows positive views of American influence in 2006 (on the y-axis) against positive views of American influence in 2013 (on the x-axis). There are big differences across countries; in 2013, only 17% of Russians considered American influence mainly positive, in contrast to 82% of Ghanaians. Interestingly, there are also (smaller) changes over time for a given dyad (a 45° line is included in the graph). For instance, Mexican perceptions of America’s influence rose from being 10% mainly positive in 2006 to 41% in 2013, while French perceptions rose from 25% to 52% over the same period of time, and Brazilian from 33% to 59%. The analogous data for mainly negative views of the United States are portrayed in the top-right quadrant. Here too, there is considerable dispersion across both countries and time. The two graphs in the bottom part of the figure are analogous, but present data about how the US perceives the (mainly positive and negative) global influences of other countries. Figure 2 is the analogue for China.

I use a conventional data set and a standard “gravity” model of international trade to account for other influences on bilateral exports besides soft power. My econometric model includes a comprehensive set of country-year fixed effects (one set each for the exporter and importer), which control for a host of influences on bilateral exports other than soft power. For instance, any boost to American sales arising from the 2008 election of Barack Obama is taken out by the 2008 American exporter fixed effect; similarly, any effect on Egyptian imports arising from the 2011 Arab Spring is taken out by the 2011 Egyptian importer fixed effect. Anything that is specific to a country and a year – such as the size of its economy, population, culture, or military spending, for either the exporter or the importer – is accounted for by the fixed effects.

What is the additional effect on exports from country x to country y of the (mainly positive) global influence of x as perceived by y? The statistical estimate is an economically large elasticity of .5; a one percent (not one percentage point!) increase in the exporter’s positive world influence, as perceived by the importer, is associated with a .5 percent increase in bilateral exports. This effect is statistically large; the robust t-ratio exceeds six and thus is different from zero at all reasonable confidence levels. The results from the other measures of world influence are consistent. An exporter perceived to be exerting more of a negative influence experiences exports that are lower by an economically and statistically significant amount. Consistently, the perceived net effect tabulated there is also positive, and statistically large.

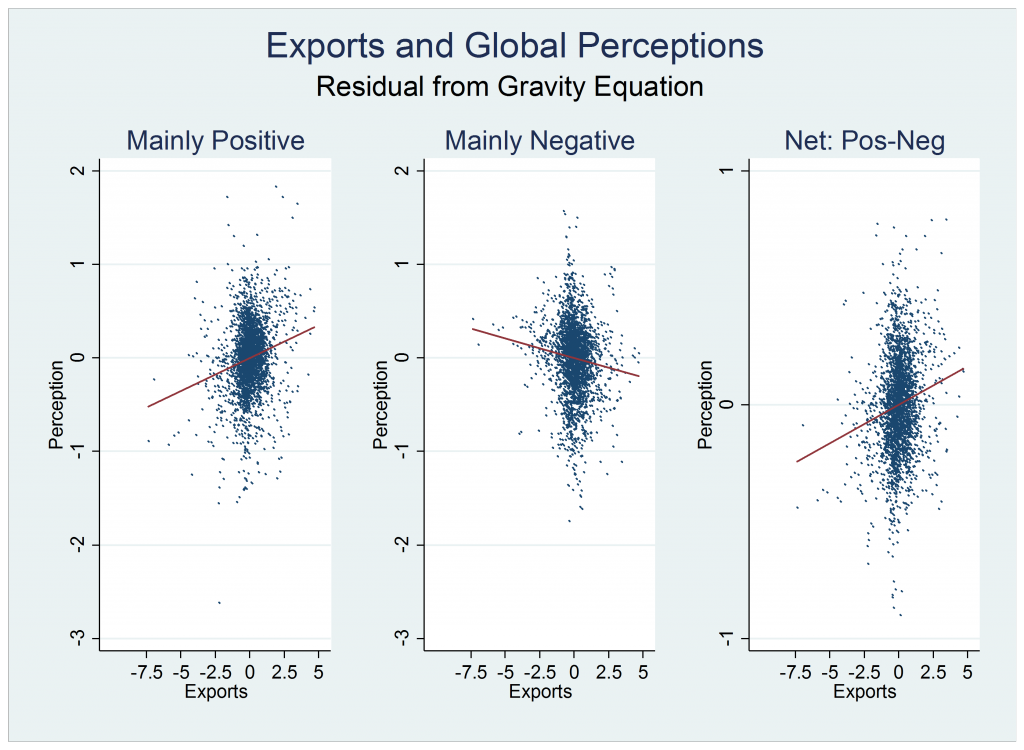

Figure 3 provides visual evidence of the effect of perceived influence on (log) exports. First, I regress log exports on all export determinants except the effect of influence. Next, I regress influence on the same set of regressors. I then plot the influence residual (on the y-axis) against the export residual (on the x-axis). There are three different scatter-plots, one for each of the three measures of influence (log mainly positive, log mainly negative, and net), each with the corresponding least squares fitted line. The effect of influence is visible, though not overwhelming; the effect does not appear to be driven by outliers.

The conclusion

Countries that are admired for their positive global influence reap the benefit of higher exports, holding other things constant. This result is economically and statistically significant, reasonably (but not completely) robust to a variety of potential econometric issues, and seems intuitive. It may also be important; if the benefits of soft power include an unappreciated export boost, too little soft power may be generated. Countries like Iran, North Korea, Pakistan and Israel that are maligned as a mostly negative influence in the world suffer lower exports than they otherwise would.

♣♣♣

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

Featured image credit: Gary Denham CC BY-SA-2.0

Andrew K. Rose is the B.T. Rocca Jr. Professor of International Business in the Economic Analysis and Policy Group, Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley; he serves as Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, and Chair of the Faculty. He is also a Research Associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research (based in Cambridge, MA), and a Research Fellow of the Centre for Economic Policy Research (based in London, England). He received his Ph.D. from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, his M.Phil. from Nuffield College, University of Oxford, and his B.A. from Trinity College, University of Toronto.

Andrew K. Rose is the B.T. Rocca Jr. Professor of International Business in the Economic Analysis and Policy Group, Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley; he serves as Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, and Chair of the Faculty. He is also a Research Associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research (based in Cambridge, MA), and a Research Fellow of the Centre for Economic Policy Research (based in London, England). He received his Ph.D. from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, his M.Phil. from Nuffield College, University of Oxford, and his B.A. from Trinity College, University of Toronto.

Hello! I am currently a business student and am very interested in international business. I was just wondering what made you interested in finding data on the correlation between positive international business and number of exports? Also, I am curious to know, as a Research Associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research, what are some other topics have you completed research on? Do you mainly focus on international economics?

Thank you!