In late February, UK Prime Minister David Cameron announced that the referendum on the country’s continued membership of the European Union (EU) would be held on 23 June. Over the following weekend, a number of leading Conservative MPs announced their support for the campaign to leave the EU – ‘Brexit’. The pound sterling declined as trading opened on the Monday morning, losing close to 2% of its value relative to the dollar and 1.5% relative to the euro on the first day of trading following these news stories.

A number of commentators have expressed concern that this is merely the tip of the iceberg and that the run-up to the referendum will be a period of significant financial volatility. According to these observers, this presages the economic and financial troubles that Brexit would bring.

Others have pointed out that financial markets are volatile by their nature, tend to over-react and are hard to forecast. Moreover, the FTSE 100 stock market index actually increased on the Monday following the referendum announcement and held its value through the following week.

A bumpy ride to Brexit

The first question in the Centre for Macroeconomics (CFM) survey asked panel members to assess whether the debate on Brexit is likely to lead to a higher level of exchange rate volatility in the coming months.

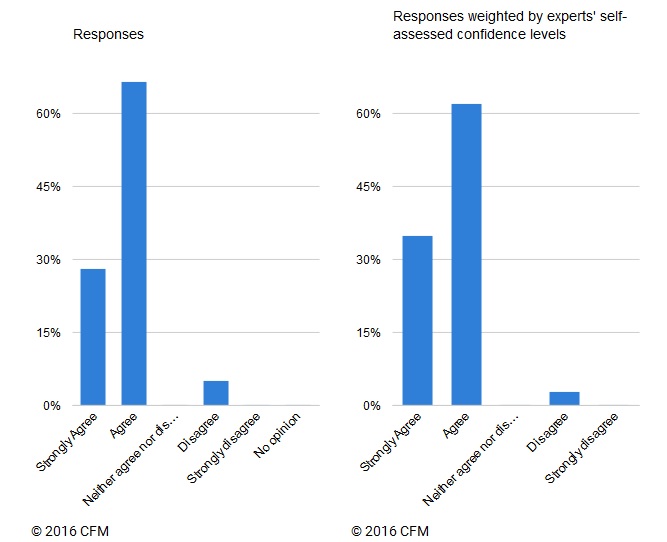

Question 1: The value of the pound fell sharply this week. Do you agree that the public debate on Brexit can be expected to (continue to) lead to a substantial increase in exchange rate volatility in the upcoming months?

Figure 1. Exchange rate volatility

Thirty-nine panel members answered this question. The respondents are nearly unanimous and either strongly agree or agree that exchange rate turbulence can be expected. In the history of the CFM survey, the respondents have never been so united in their views.

Important reasons given for this increase in volatility are uncertainty about the outcome of the referendum and uncertainty about the implications of Brexit. Several panel members predict that volatility will increase if polls show a close race.

Sir Christopher Pissarides (London School of Economics, LSE) expects that sterling will weaken if the ‘Leave’ campaign gains momentum. But uncertainty is expected to remain high even if Brexit becomes highly likely. Sir Christopher Pissarides points to the political fallout from such a result and ‘to the future of the government (and Cameron-Osborne in particular)’ and also to ‘the uncertainties relating to the new trade and financial arrangements with the EU in the event of a no vote.’

Wouter Den Haan (LSE) says that ‘Even if Brexit were a sure thing, then there still would be lots of uncertainty about the UK and European economy in the post-Brexit world. As markets try to understand what could happen and what the likelihoods of these outcomes are, market prices are bound to display a lot of volatility.’ Tony Yates (Birmingham) points to the possibility of another Scottish referendum on independence as an additional source of volatility.

Two dissenting voices disagree that markets will be volatile going forward, but provide very similar views to the majority on the factors that may drive volatility. Martin Ellison (Oxford) and Andrew Mountford (Royal Holloway) both opine that last weekend’s news is likely to turn out to be the biggest event in the run-up to the referendum, so that the worst is already behind us. Andrew Mountford predicts that ‘as time progresses opinion polls will show a clear majority in favour of the UK remaining in the EU and so the uncertainty surrounding the referendum will subside.’

Brexit risks

The second question of the CFM survey asked about the risk that the possibility of Brexit will lead to more uncertainty and volatility in financial markets and the broader economy.

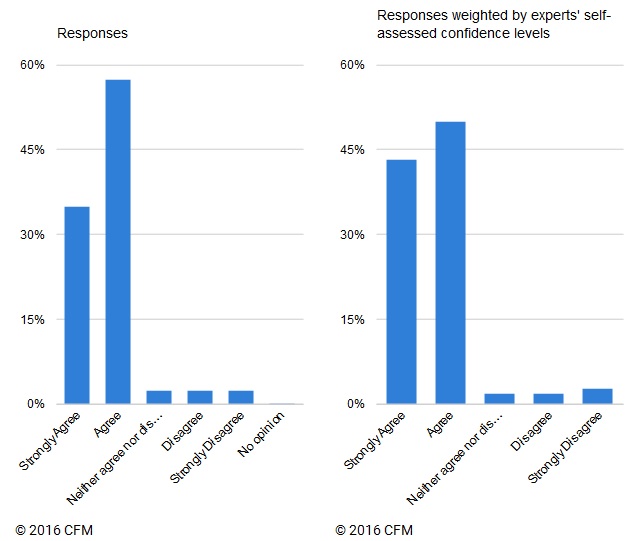

Question 2: Do you agree that the possibility of Brexit significantly increases uncertainty and volatility in financial markets and the economy in general?

Figure 2. Financial rate volatility and other economic risks

Of the 40 respondents who answered this question, 93% either strongly agree or agree that the possibility of Brexit is associated with financial market and other economic risks to the UK economy. This percentage does not change when the answers are weighted with self-assessed confidence level, but the fraction that strongly agree increases from 35% to 43%.

The main concern expressed is uncertainty about the post-Brexit world. Richard Portes (London Business School) notes that ‘even the proponents of Brexit have no clear view of what would happen – indeed, of what they would like to see happen, in regard to our subsequent relationship with the EU.’ Several respondents point to the lengthy and uncertain process of renegotiating access to the single market. As Costas Milas (Liverpool) puts it, ‘we currently have a season ticket in Europe. Why on earth would we want to switch to individual (and much more expensive) tickets?’

As a result of this uncertainty, firms are likely to take a ‘wait and see’ attitude, which will result in a drop in investment. Ricardo Reis (LSE) expects that ‘investment of firms based in the UK with significant international relations will be delayed until the outcome of the referendum is clear.’ Paolo Surico (London Business School) also predicts lower investment in the quarters following the referendum should the ‘Leave’ camp win.

In addition to the direct impacts on the UK economy, some panel members express concerns about the broader national and international implications of exiting the EU. Morten Ravn (University College London) worries that Brexit would trigger another Scottish referendum and may lead to changes in the remaining EU. Panicos Demetriades (Leicester) notes that Brexit could be a ‘catalyst for other significant changes in the EU. It is not impossible that other countries may follow; it is also not unlikely that Grexit uncertainty may resurface again.’

A small number of respondents disagree. Patrick Minford (Cardiff) makes a distinction between financial markets, including the value of the pound, and the real economy: ‘The economy’s behaviour depends on fundamentals that will be greatly improved by Brexit. Short-term falls in sterling will actually stimulate the economy in the short run.’

Jagjit Chadha (Kent) agrees with the majority that ‘any increase in uncertainty may impact on consumption and investment plans.’ But he also points out that the uncertainty argument goes both ways: ‘the referendum will resolve membership uncertainty in one direction or the other; it will allow us to get on with the question of Britain’s future with at least this question resolved for a generation or more.’

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This article is based on the results of the survey Brexit and financial market volatility, conducted by the Centre for Macroeconomics (CFM), and published on 25 February 2016.

- This post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: – Flickr the Sao Paulo Stock Exchange CC-BY-2.0

Wouter Den Haan is Professor of Economics at LSE and Co-Director of the Centre for Macroeconomics. HIs main research interests are in macroeconomics, the role of frictions in financial and labour markets for business cycles, business cycle models with heterogeneous agents and computational economics. He holds a PhD in Economics from Carnegie Mellon University.

Wouter Den Haan is Professor of Economics at LSE and Co-Director of the Centre for Macroeconomics. HIs main research interests are in macroeconomics, the role of frictions in financial and labour markets for business cycles, business cycle models with heterogeneous agents and computational economics. He holds a PhD in Economics from Carnegie Mellon University.

Martin Ellison is a British economist. He is Professor of economics at the University of Oxford and a Fellow of Nuffield College. He gained his PhD in economics in 2001 from the European University Institute in Florence. Ellison has worked as a consultant for the Bank of England and as a Professor at the University of Warwick before his current affiliation at the University of Oxford. He is specializing in macroeconomics; his PhD thesis was titled “Money Matters: Four Essays on Monetary Economics”. His main research interest is monetary policy and he is editing several journals in the field of economics.

Martin Ellison is a British economist. He is Professor of economics at the University of Oxford and a Fellow of Nuffield College. He gained his PhD in economics in 2001 from the European University Institute in Florence. Ellison has worked as a consultant for the Bank of England and as a Professor at the University of Warwick before his current affiliation at the University of Oxford. He is specializing in macroeconomics; his PhD thesis was titled “Money Matters: Four Essays on Monetary Economics”. His main research interest is monetary policy and he is editing several journals in the field of economics.

Ethan Ilzetzki is Assistant Professor of Economics at LSE. He is an Associate at the Centre for Macroeconomics and the Centre for Economic Performance. HIs research interests are in macroeconomics, international finance and fiscal policy. He holds a PhD in Economics from the University of Maryland.

Michael McMahon is Associate Professor of Economics at Warwick University. He is also a a Research Associate with the Centre for Macroeconomics (CFM), Research Affiliate with the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and the Centre for Applied Macroeconomic Analysis (CAMA, ANU), International Consultant Economist at the IMF’s Singapore Training Institute and a Visiting Scholar at the Bank of England. He holds a PhD in Economics from LSE. Dr. McMahon’s research interests are macroeconomics of business cycles; monetary economics; inventories and applied econometrics.

Michael McMahon is Associate Professor of Economics at Warwick University. He is also a a Research Associate with the Centre for Macroeconomics (CFM), Research Affiliate with the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and the Centre for Applied Macroeconomic Analysis (CAMA, ANU), International Consultant Economist at the IMF’s Singapore Training Institute and a Visiting Scholar at the Bank of England. He holds a PhD in Economics from LSE. Dr. McMahon’s research interests are macroeconomics of business cycles; monetary economics; inventories and applied econometrics.

Ricardo Reis is Professor of Economics at LSE, on leave from Columbia University. He received his PhD in Economics from Harvard University in 2004. He has published extensively and has had a number of editorial positions in leading academic journals. He is a Research Associate at CFM and NBER, a Research Fellow at the Centre for Economic Policy Research, and is also a member of NBER’s Macro Annual advisory board. Dr Reis is an academic consultant of the Federal Reserve Board of New York and Richmond.

Ricardo Reis is Professor of Economics at LSE, on leave from Columbia University. He received his PhD in Economics from Harvard University in 2004. He has published extensively and has had a number of editorial positions in leading academic journals. He is a Research Associate at CFM and NBER, a Research Fellow at the Centre for Economic Policy Research, and is also a member of NBER’s Macro Annual advisory board. Dr Reis is an academic consultant of the Federal Reserve Board of New York and Richmond.