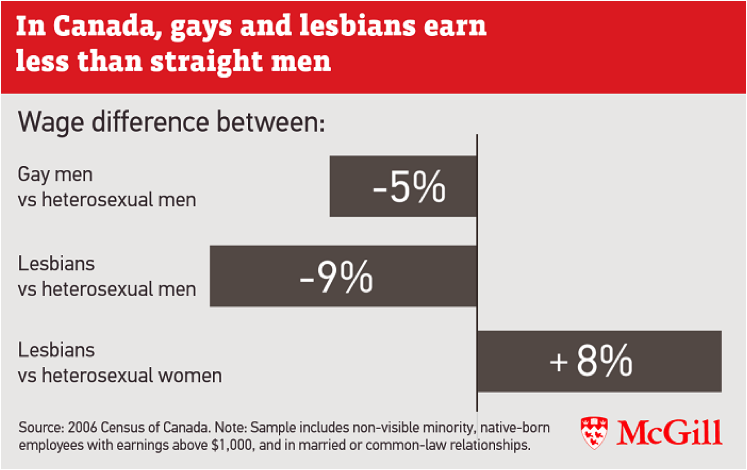

It is now well accepted that gender is a major source of differentiation in the labour market. On average women earn less than men, even when they have similar education, and work full-time and in identical occupations. Until recently, little information was available on how sexual orientation factored into people’s work experiences. The availability of new data has allowed researchers to explore whether labour market opportunities and rewards are also stratified by sexual orientation. To date, studies have found that gay men earn less than heterosexual men and lesbians earn more than heterosexual women but still less than all men.

One explanation for these wage gaps may be that gay men and lesbians differ from heterosexual men and women in important ways, such as weeks and hours worked, family formation, education, occupation or industry of employment. Differences in these characteristics could explain difference in earnings by sexual orientation; however, in statistical models that control for these characteristics, differences in earnings persist. Researchers often interpret wage gaps that remain after accounting for these characteristics as discrimination. In other words, it is argued that employers and customers have a preference working with or doing business with straight men, rather than gay men. The wage advantage for lesbians relative to straight women is commonly interpreted as positive discrimination, i.e. since lesbians are less likely to be married and have fewer children, employers may perceive them as more committed and less encumbered by family responsibilities than straight women. Taken another way, lesbians may experience less discrimination than straight women because employers perceive them to be less burdened by family and childcare responsibilities.

As a relative leader in the provision of civil rights for sexual minorities, Canada is an important site for studying the labour market experiences of gay men and lesbians. In 2003 Canadian provinces began recognizing same-sex marriage, culminating in the federal legalization of same-sex marriage on July 20, 2005–making Canada the fourth country in the world to federally legalize same-sex marriage. Ten years earlier the Supreme Court of Canada maintained that sexual orientation was subject to coverage under federal anti-discrimination laws outlined in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. In addition to federal protections, all provincial human rights charters and laws prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation in private housing and labor markets. As a result of this legal setting, the 2006 Census of Canada provides data on married and cohabiting same-sex couples across the nation — one of the first in the world to do so. Statistics Canada also went to considerable lengths to ensure that same-sex couples were correctly counted in the 2006 census. For instance, the Canadian Census asks respondents directly if they are in a same-sex common-law relationship. This is an improvement over US census data where researchers must infer a conjugal relationship between same-sex adults in a household.

In a recent study published in Gender & Society, we use Canadian Census data to explore how various mechanisms contribute to wage gaps between gay men and straight men and lesbians and straight women. Our most conservative estimates find a ranking of labor market outcomes by sexual orientation in Canada. Gay men earn less than heterosexual men and lesbians earn more than heterosexual women but still less than all men. These conservative estimates account for known determinants of earnings, such as education, weeks/hours worked, detailed occupation, industry of employment, and family situation.

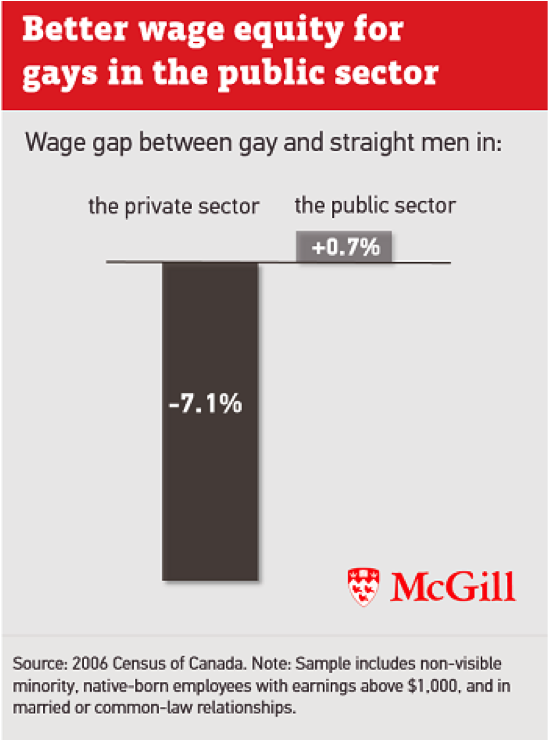

We also find that gay men and lesbians are very highly educated, which leads to employment in lucrative occupations but within these occupations gay men and lesbians earn significantly less than straight men. Wage gaps are reduced in the public sector for straight women, gay men, and lesbians. For gay men wage gaps in the public sector were statistically indistinguishable from heterosexual men but much larger in the private sector (see figure below). Lastly, we find that straight women experience a penalty for having children, while straight men have a premium, and both receive premiums for being married; however, the presence of children and marriage have no effect on the earnings of either gay men or lesbians in conjugal relationships.

In a separate study, entitled Does it Get Better? I argue that the last decade witnessed considerable progress in attitudes and visibility of gay men and lesbians in Canada, including the legalization of same-sex marriage. Surprisingly, these improvements did not help to narrow wage differentials by sexual orientation. In fact, there was virtually no change in sexual minority wage gaps between 2000 and 2010. In another study, we also explore how these wage gaps vary across the county, arguing that local labour markets may provide unique conditions that could ameliorate or exacerbate wage differentials. We find that wage gaps are largest in areas of Canada where attitudes are less tolerant toward sexual minorities, i.e. rural areas. In areas with more liberal attitudes (Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver) wage gaps are smaller.

Research shows that sexual orientation is an important dimension of labour market stratification in many countries. Although Canada has a relatively long history of employment protections and a high level of acceptance for sexual minorities, labor markets are stratified by sexual orientation. Gay men appear to make choices to improve their economic fortunes, such as investing in high levels of education and working in high paying occupations; however, it is within these occupations that gay men earn less. For lesbians, investments in higher education, sorting into higher paying occupations, industries and working more hours per week play a significant role in their wage advantage, relative to straight women. A smaller, although not insignificant, portion arises from differences in returns to these characteristics for lesbians. This study has answered many important questions regarding labor market stratification by sexual orientation in Canada; however, many questions remain. Research on the economic lives of gay men and lesbians continues to offer an exciting and pressing arena for future research not only in Canada but all over the world.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This post is based on the authors’ paper Gay Pay for Straight Work – Mechanisms Generating Disadvantage, in Gender & Society, August 2015 vol. 29no. 4 561-588.

- This post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: NEC Corporation of America CC-BY-2.0

Sean Waite is a PhD candidate in sociology and graduate trainee at the Centre on Population Dynamics at McGill University. For information on his research please click here: (http://www.seanwaite.ca).

Sean Waite is a PhD candidate in sociology and graduate trainee at the Centre on Population Dynamics at McGill University. For information on his research please click here: (http://www.seanwaite.ca).

Nicole Denier is a PhD candidate in sociology and graduate trainee at the Centre on Population Dynamics at McGill University. For more information about her current research click here (www.nicoledenier.com).

Nicole Denier is a PhD candidate in sociology and graduate trainee at the Centre on Population Dynamics at McGill University. For more information about her current research click here (www.nicoledenier.com).

1 Comments