Extreme rainfall during December 2015 resulted in widespread flooding across northern England, Scotland and Ireland. With the costs of this one event potentially exceeding $2 billion, an important policy question is why so many people are hit by flooding, particularly in locations that are repeatedly inundated.

The recent events in the British Isles are just one example of a major global problem. According to media reports collated by the Dartmouth Flood Observatory, between 1985 and 2014, floods worldwide killed more than half a million people, displaced over 650 million people and caused damage in excess of $500 billion (Brakenridge, 2016).

Other datasets tell of even farther reaching impacts: according to the International Disaster Database, in 2010 alone, 178 million people were affected by floods and total losses exceeded $40 billion (Guha-Sapir et al, 2016). To these direct costs we should add longer-term costs of disruptions to schooling, increased health risks and reduced incentives to invest.

So it seems important to understand why so much is lost to floods. One might argue that the private risks of floods are balanced by the private gains from living in flood-prone areas. But in fact, flood plains tend to be overpopulated because the cost of building and maintaining flood defences is often borne by governments and not by private developers. This problem of an inadvertent subsidy to build on flood plains is made worse because the costs of flood recovery are also borne by governments and non-governmental organisations. This situation creates potential for misallocation of resources, and forces society to answer difficult distributional questions.

Our research examines how prevalent it is for economic activity to concentrate in flood-prone areas, and whether or not cities adapt to major floods by relocating economic activity to safer areas.

Large-scale urban floods

In our empirical analysis, we study the impact of large-scale urban floods. We use new data from spatially disaggregated inundation maps of 53 large floods, which took place between 2003 and 2008. Each of these floods displaced at least 100,000 people and taken together, the floods affected 1,868 cities in 40 countries, mostly in the developing world. Figure 1 shows the locations of the large flood events included in our analysis. We study the local economic impact of the floods using satellite images of night lights at an annual frequency.

Figure 1: Locations of cities affected by large flood events, 2003-08

Notes: City sizes are inflated to make them visible on a map of the entire world. Smaller dots correspond to cities not affected by any of the floods in our sample. The number of floods in the legend refers to the number of years in 2003-08 during which each city was affected by a flood that displaced a total of 100,000 people or more.

Our data show that the global exposure of urban areas to large-scale flooding is substantial, with low-lying urban areas flooded much more frequently. Globally, the average annual risk of a large flood hitting a city is about 1.3% for urban areas that are more than 10 metres above sea level, and 4.9% for urban areas at lower elevation. In other words, urban areas that are less than 10 metres above sea level face an average annual risk of about one in 20 of being hit by a large flood. Of course, this average masks considerable variation across locations.

Local flooding risk results from a complex combination of local climate, permeation and topography, among other factors. Some urban areas – even some located at low elevation – will flood rarely, if ever. At the other extreme, some urban areas flood repeatedly. In our sample, about 16 per cent of the cities that are hit by large floods are flooded in multiple years.

We also find that even though low- lying areas are more likely to be flooded, they concentrate a higher density of economic activity, as represented by night light intensity. There is a disproportionate concentration of economic activity in low elevation areas even in areas that are prone to extreme precipitation, where the risk of large-scale flooding is highest.

Local impact and responses

When we analyse the local economic impact of large floods, we find that on average they reduce a city’s economic activity (as measured by night light intensity) by between 2% and 8% in the year of the flood. But recovery is relatively quick: night lights typically recover fully within a year of a major flood, even in the hardest-hit low-lying areas.

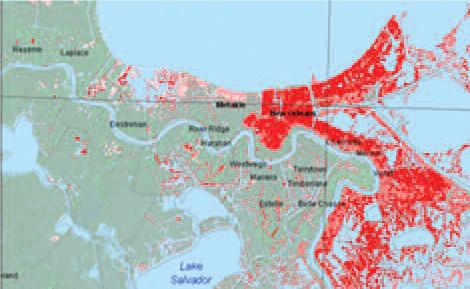

Figure 2 illustrates this pattern of recovery in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, which hit the city of New Orleans in 2005. But it is worth noting that New Orleans is unusual in our sample as it is much richer (and much better lit) than most of the flooded cities.

Our finding that economic activity recovers after floods even in low-lying areas suggests that there is no significant adaptation, at least in the sense of a relocation of economic activity away from the most vulnerable locations. With economic activity fully restored in vulnerable locations, the scene is sadly set for the next round of flooding.

A possible motivation for restoring vulnerable locations is to take advantage of the trading opportunities – and amenity value – offered by water-side locations.

But we find that economic activity is fully restored even in low elevation locations that do not enjoy the offsetting advantages of being near a river or coast.

Our results are also robust to restricting our sample to cities with at least some areas more than 10 metres above sea level. This means that there is no movement to higher ground in the aftermath of large floods even within cities where such movement is possible.

One exception to our general finding that cities do not adapt in response to large floods is evident in the subset of recently populated parts of cities (those that had no night lights in 1992). We find that in these recently populated urban areas, flooded areas show a larger and more persistent decline in night light intensity, indicating some relocation of economic activity in response to flooding. This may be either because flood risk was under-appreciated in these newer urban locations or because these areas had fewer past investments, so moving away was less costly.

Figure 2: Inundation and night light intensity maps for Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans.

Panel A

Panel B

Panel C

Panel D

Future floods

Our findings are important for a number of reasons. First, global warming and especially rising sea levels are expected to exacerbate the problem of flooding in many of the world’s cities. Second, there is a continuing trend towards increased urbanisation around the world, especially in poor regions.

As urbanisation progresses, it is important to know whether cities adapt and how their populations can avoid dangerous areas. Our results suggest that flooding poses a challenge for urban planning because adaptation away from flood- prone locations cannot be taken for granted even in the aftermath of large and devastating floods.

Third, floods disproportionately affect poor countries. Given the scale of human devastation and its potential damage to human capital formation (for example, disruptions to education or harm to people’s health), this is an important development issue. To illustrate, planning and zoning laws and their enforcement are typically weak in developing countries. Consequently, slums and other informal urban settlements tend to develop on cheap land with poor infrastructure, including flood-prone areas.

More than 860 million people live in flood-prone urban locations worldwide, and this population increased by about six million a year between 2000 and 2010. Our finding that low elevation locations concentrate much of the economic activity even in poor urban areas with erratic weather patterns highlights the tragedy of the recurring crisis imposed by flooding.

Fourth, recovery assistance after flooding is an important part of international aid. Our findings suggest that in some circumstances, part of the aid and reconstruction efforts should be targeted at moving economic activity away from the most flood-prone areas to mitigate the risk of recurrent humanitarian disasters.

Finally, our results are relevant for discussions of the costly effects of ‘path dependence’ (Bleakly and Lin, 2012; Michaels and Rauch, 2013). Our findings suggest that parts of cities that are built in flood-prone areas may be locking in exposure to flood risk for a long time, even when circumstances and the global climate change.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This article was originally published in CentrePiece, the magazine of LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance (CEP), and is based on the authors’ paper Flooded Cities, CEP Discussion Paper No.1398.

- This post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: DesignRaphael Ltd, for CEP.

Adriana Kocornik-Mina is at Alterra- Wageningen UR in the Netherlands

Adriana Kocornik-Mina is at Alterra- Wageningen UR in the Netherlands

Guy Michaels is associate professor of economics at LSE and a research associate in CEP’s labour markets programme.

Guy Michaels is associate professor of economics at LSE and a research associate in CEP’s labour markets programme.

Thomas McDermott is at University College Cork.

Thomas McDermott is at University College Cork.

Ferdinand Rauch of the University of Oxford is a research associate in CEP’s trade programme.

Ferdinand Rauch of the University of Oxford is a research associate in CEP’s trade programme.