In the run up to the 2008/09 Great Recession, belief in monetary policy as a countervailing force against potential hard-landings evolved to a near article of faith. During the reconstruction from the ensuing wreckage, central banks across the globe engaged in liquidity expansion exercises in a scale that defied precedents. About seven years later, there seems to be a growing consensus that the silver bullet has lost its piercing power.

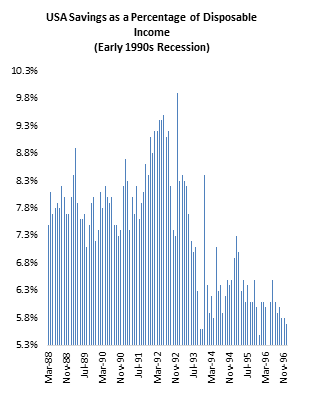

Indeed, G20 Central Bankers and Finance Ministers have called for a coordinated departure from monetary and shift towards fiscal policy as the main lever in nudging global growth forward. Even Ben Bernanke, arguably one of the 21st century’s most influential monetary policy wonks, has written that the tool is “reaching its limits”. And markets have suggested that the doubts should not be trifled with ─ in Japan, low inflation (bordering on deflation) remains that bad penny that keeps coming back, never mind that the country has had about four years of Abenomics, an agenda heavily anchored on accommodative monetary policy.

Figure 1

Source: Bloomberg data

The Euro’s reaction to Mario Draghi’s dovish signals in March 2016 also suggested that markets either took the unintended cue from the European Central Bank or opted to give it a chilling go-by altogether.

To think of this U-turn in policy perspective as nascent is, however, to miss the point; the objective and limits of monetary policy have been a matter of unresolved debate for decades. In his iconic 1968 paper titled ‘The Role of Monetary Policy’, Milton Friedman expressed fears that “we are in danger of assigning monetary policy a larger role than it can perform, in danger of asking it to accomplish tasks it cannot achieve and, as a result, in danger of preventing it from making the contribution it is capable of making”.

Friedman, for instance, took issue with employment rate targeting as a cogwheel in driving monetary adjustments ─ a stance that, in contemporary economics, would be widely deemed heretical and it would seem the apparent loss of mojo by monetary policy confirms Friedman’s fears.

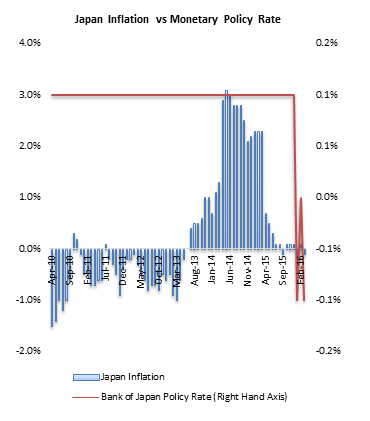

But what if we are seeking answers in the wrong place? What if consumerism has evolved considerably post-Great Recession and economic models are behind the curve in adjusting to the new behaviour? Consider, for instance, that seven years since the end of the Great Recession , the US’s savings to GDP ratio has corrected but not to the pre-crisis lows, unlike what happened after the early 1990’s recession.

Figure 2

Source: Bloomberg data

Figure 3

Source: Bloomberg data

Of consumer apprehension and tightened purse strings

Perhaps we are facing a new kind of consumer, one who is far less optimistic about the trajectory of the global economy and more frugal than their yester self. If monetary policy was intended to grease the consumption wheels, Keynes’ Paradox of Thrift ─ consumers’ higher preference for savings than consumption in the face of economic downturn ─ could be the factor throwing a monkey wrench into the equation and dis-spiriting central bankers.

We could be facing a consumer who refuses to lend themselves to traditional incentives, opting instead to wait out the storm. Maybe the consumer does not need greater access to credit, just less uncertainty as to where the next arc of the global growth curve will be. In truth, a sense of certainty is quite elusive in light of ongoing developments around the globe: the threat of Brexit hangs over the European Union as the June referendum draws near; the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) seem to have run out of mojo; and in Africa, the ‘Rising’ narrative has lost its charm as subdued commodity prices reveal economies plagued by imbalanced engines of expansion.

As the world contemplates shifting gears from monetary to fiscal policy, one is left to wonder whether the latter will help dispel consumer apprehension about the global economy or national treasuries are simply taking the proverbial Hail Mary pass from central banks.

Africa must chart its course

In all this, however, Africa much chart its course for stimulating growth. The immediate aftermath of the 2008/09 recession suggested a number of economies in the continent are adept at adopting counter-cyclical fiscal measures to mitigate crises. Today, however, below-target commodity prices are negating the continent’s fiscal robustness and presenting a head scratcher for policy makers.

In its 2016 Country Economic Memorandum (Kenya), the World Bank proposes promoting and thereafter leveraging domestic savings as a means to meet government financing needs, an approach that can be adopted across the continent especially as foreign exchange volatility diminishes the prospects of tapping into global markets.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This post gives the views of its author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: AMISOM Public Information, Public Domain

Julians Amboko is a Research Analyst with StratLink Africa Ltd, a Nairobi-based financial advisory firm focusing on emerging and frontier markets. He covers macroeconomic research and analysis for Sub-Saharan Africa, including markets such as Nigeria, Kenya, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Angola.

Julians Amboko is a Research Analyst with StratLink Africa Ltd, a Nairobi-based financial advisory firm focusing on emerging and frontier markets. He covers macroeconomic research and analysis for Sub-Saharan Africa, including markets such as Nigeria, Kenya, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Angola.

1 Comments