In everyday use, by David Goehring, under a CC-BY-2.0 licence

In everyday use, by David Goehring, under a CC-BY-2.0 licence

| The Surviving Work in the UK series is produced by Surviving Work. |

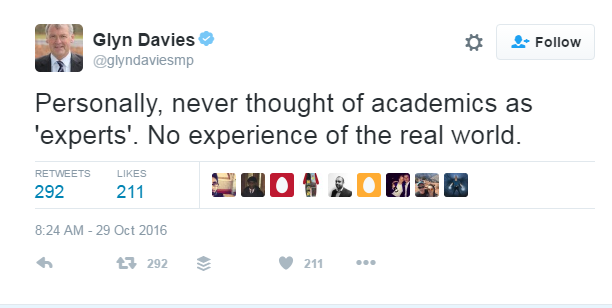

The value of academic work has come under attack – with challenges to the way we understand and measure our work implemented through the Research Excellence Framework and the newly designed Teaching Excellence Framework. Within this model and more broadly in our society the role of The Expert no longer attracts the kudos it once did. Indeed recently, Glyn Davies MP tweeted that “Personally, never thought of academics as ‘experts’. No experience of the real world”.

Predictably enough, this was not the view of the hundreds of academics who took to twitter to disagree with Mr Davies’ assertion, using the #realworldacademic hashtag. Yes, academics have smart phones and can restrict themselves to 140 characters.

Some listed their comprehensive education, others outlined the many jobs involving long hours on low pay that had been needed to put themselves through non-elite universities to get into employment. Many described the precariousness of struggling to survive on short term contracts where hourly wages don’t take into account marking, student contact time or trying to write articles so that they could progress their career. Not being paid to write anything being something of a handicap in academic life.

To a growing majority of academics, the difficulty of surviving work is experienced in the very real world including debt, depression and a profound sense of the paradoxes of teaching subjects such as decent work and employability to the next generations of working people.

Both the view that academics can avoid the problems of work and the view that we are not experienced in the ‘real world’ are wrong. The rapid growth in student numbers has, if nothing else, made it less likely that an academic will have a room to go hide in and actually think. Hot-desking and even the removal of books from offices is normal.

Significantly, the expectations of what academics produce and why has shifted radically over the last few years – where the impact of what we do increasingly measures academic success. Across the huge amount that has been written about how impact from academic work is created, there is one simple acknowledgement: what you are actually trying to do is to influence someone to take your research or ideas seriously. And then try to get them to do something about it.

Some of the impact literature focuses on the theory of impact, or how it is seen across disciplines, or how the definition of impact needs to be developed. On a more practical side, there are handbooks that outline tools, processes and platforms to help the time-pressured researcher to ‘do’ impact. If you see impact as winning friends and influencing people, an important aspect involves actual interaction with actual other human beings, something which under this stereotypical view of academics, we’re not very good at. There are several key groups that academics have to influence in the daily course of their work: their students, their peers and senior colleagues, other academics in their fields, promotion panels, journal editors, conference organisers and so on.

In terms of impact, ‘people’ also can include research subjects and research users. There are two aspects here. Many academics work closely, and indeed co-produce research, with partner organisations that can also be their research subjects. They often spend months and years getting to know people within businesses, organisations, groups, communities, and government bodies. This brings many benefits but also difficulties that academics must work through with their partners, funders and universities.

In the case of businesses, the most difficult part of that is finding the right partnerships in the first place. Businesses need to find someone with the right expertise, and academics must be able to persuade business leaders that the research or interaction will have value over and above information that already exists out in the world.

Building this trust between academics and businesses is something that usually takes significant time, resources and people skills. To do that academics must put themselves in the shoes of their business colleague, to understand what is in it for them. They then have to communicate that effectively and then negotiate its continuation successfully so that both parties are able to see the relationship as valuable. Once trust has been built up though, and relationships created, maintaining that link is easier than it is within government bodies, for example. This is contrary to much of the perceived wisdom about researching in business – where it is assumed that businesses will not allow access to a critical outsider for fear of skeletons coming out of cupboards.

What the research shows is that where academics are able to make friends in business, they stand a higher chance of influencing people than through the usual governmental and research channels. And a high percentage of businesses who collaborate with academics describe their relationship as successful.

The second aspect comes after: when research is published and academics attempt to influence research users to engage with it, and in an ideal world, change something because of it. Distilling down some of these lessons from impact handbooks highlights the usefulness of finding a key graph, figure or statistic. For research users, these types of evidence are easy to grasp, they are shareable within their organisation, and can lead to eureka moments that can show them how their organisation could make a difference to a particular situation. (But these have to be carefully handled as this interesting case of research on educational attainment shows.) Research that utilises personal stories within it can be a powerful way of putting complex situations into a context that can be understood and empathised with. And here too, trusted relationships – the ones that take time and effort to build and maintain, are difficult and may lead to conflict and are therefore scary – are vital.

The ‘ideal type’ of academics can sometimes be seen as engaged but distant, knowledgeable but not connected to the real world. There will no doubt be some in the profession for whom this applies, and others that seek to emulate it. However this post, albeit not a ‘how to’ guide, is intended to argue that engaging in real world relationships is not in any way outside of academics’ expertise, that being human (for example crying) within the academic workplace is acceptable, and that it will be this very showing of emotional engagement that will help create impact from our research.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- For the full list of articles in the Surviving Work in the UK series, click here; for a list of contributors to the series, click here.

- The post gives the views of its author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy.

Jane Tinkler is currently Senior Prize Manager for the Nine Dots Prize, a major new initiative for the social sciences. It aims to stimulate research into vital but under-examined questions with a relevance to today’s world. It will launch in October 2016. She recently spent a year seconded to the UK Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology (POST) as Senior Adviser in social science. She has been a social science researcher for nearly ten years working on applied projects with government, civil society and academic partners. Prior to joining POST, she was based in the Public Policy Group at the London School of Economics where most recently she worked on the impact of academic research in the social sciences. Her recent publications include: (with Simon Bastow and Patrick Dunleavy) (2014) The Impact of the Social Sciences: How academics and their work make a difference

Jane Tinkler is currently Senior Prize Manager for the Nine Dots Prize, a major new initiative for the social sciences. It aims to stimulate research into vital but under-examined questions with a relevance to today’s world. It will launch in October 2016. She recently spent a year seconded to the UK Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology (POST) as Senior Adviser in social science. She has been a social science researcher for nearly ten years working on applied projects with government, civil society and academic partners. Prior to joining POST, she was based in the Public Policy Group at the London School of Economics where most recently she worked on the impact of academic research in the social sciences. Her recent publications include: (with Simon Bastow and Patrick Dunleavy) (2014) The Impact of the Social Sciences: How academics and their work make a difference

Well there are alternatives to the Neo-liberal university! One of these would be to leave the multiversity and form Studium Generale which during the Medieval period were the forerunners of the university for wandering scholars! There would no doubt be other options but the ‘ univerdities ‘ are corrupt and will become even more so under the dictatorship of money and the fatuous obsession with economics and practical materialism!

Welcome to the world of real people and real creatures and goodbye to virtual unreality and manic mechanization! What freedom!