Workers’ satisfaction with their job is, on average, higher in a flatter organisation than in a hierarchical organisation. That is the consensus finding of a survey of leading researchers on wellbeing from around the world on the impact of different organisational structures on workers’ wellbeing.

Hierarchical versus flat organisations

In the second round of the World Wellbeing Panel monthly survey, 31 wellbeing experts from economics, sociology, and psychology were first asked whether they agree with the following statement:

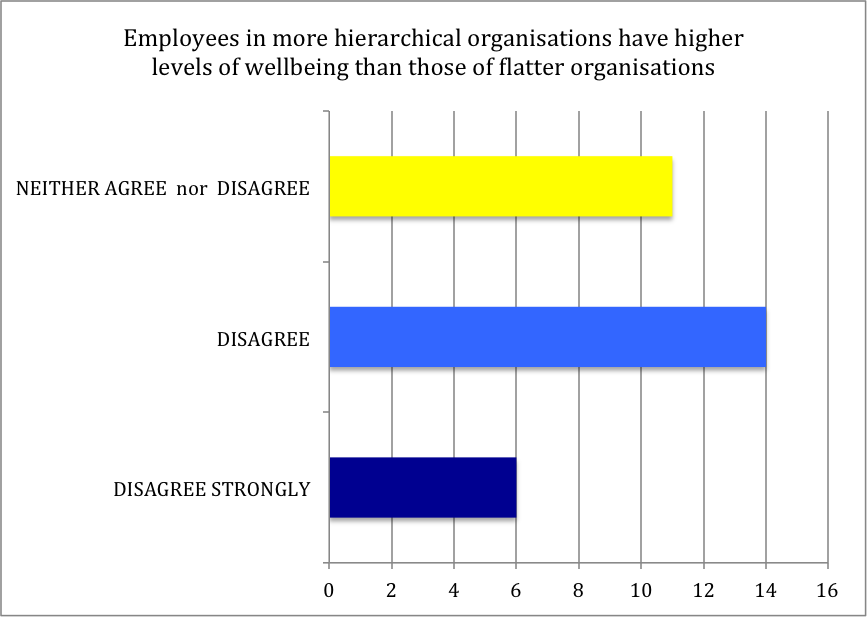

Figure 1. Survey responses to the question: ‘Do you think employees in more hierarchical organisations have higher wellbeing than those of flatter organisations?’

The overall results are clear: a total of 20 respondents either disagree or disagree strongly, and 11 have no firm opinions, implying that on average the panel disagrees that workers’ wellbeing or job satisfaction (which is what most experts have in mind when thinking about this question) are higher in more hierarchical organisations than in flatter organisations.

Among panel members who disagree strongly with the statement, one of their main reasons for disagreeing comes from research evidence that people working in hierarchical organisations experience less autonomy in their work, which is not compensated fully by higher incomes.

Stefano Bartolini and Paul Frijters point out that trust between workers is lower in more hierarchical organisations, which can be detrimental to an individual’s wellbeing. John Helliwell cites evidence that for more than two million employed people who responded to a survey in the United States, life evaluations were much higher for those who regard their immediate supervisor as a partner than for those who regard their supervisor as a boss.

Felicia Huppert directs us to evidence that opportunities for employee participation, choice and engagement are associated with much higher levels of satisfaction, morale and retention – and that such opportunities are likely to be greater in less hierarchical organisations.

She also points out that hierarchical organisations are likely to have a steeper social gradient, which would inevitably generate greater inequalities in physical and mental health for workers. What’s more, having workers who are emotionally very low is likely to have an adverse effect on others in the organisation.

But there are some panel members who cite evidence in favour of more hierarchical organisations. Dan Haybron, for example, suggests that flatter organisations may even be more stressful, given that employees are carrying more of the workload.

Jan Delhey also suggests that the relationship between organisational structure and wellbeing may depend on national culture and people’s own values. A flat organisation may be preferred and valued in the West, whereas it might cause problems in Asian cultures that accept and expect hierarchies.

The impact of tilting taxes and subsidies to favour more hierarchical organisations

The second survey question relates to policy, namely:

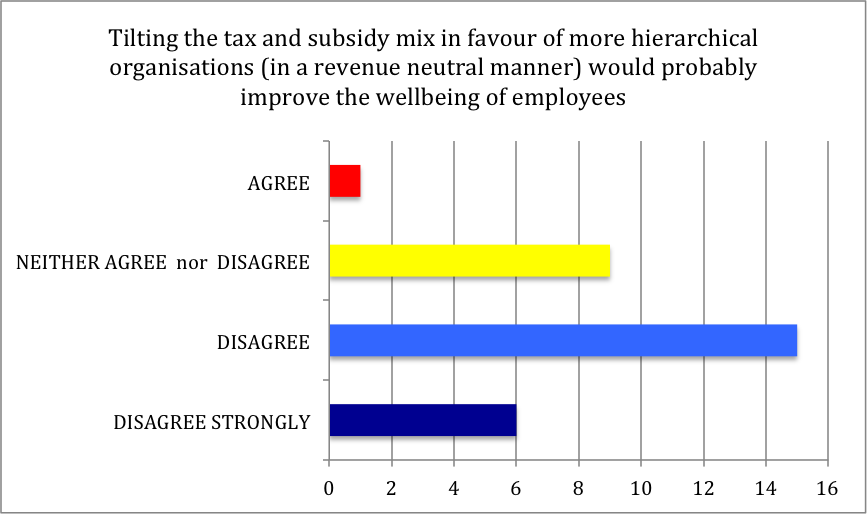

Figure 2. Survey responses to the question: ‘Do you think tilting the tax and subsidy mix in favour of more hierarchical organisations (in a revenue neutral matter) would probably improve the wellbeing of employees?’

Here, it is not surprising that almost the same number of panel members disagree with the statement: 21 in total, with one agreeing with the statement and nine having no firm opinions.

One of the main reasons for disagreeing with the statement is that workers’ wellbeing is higher in flatter organisations than in more hierarchical organisations – and so every effort should be made to reduce middle management rather than generate more.

John Helliwell states that tax systems should be simple and neutral across business forms in any case. Christopher Barrington-Leigh, who agrees with the statement, points out that tilting the tax and subsidy may reduce pay inequalities, which should more than compensate for the potential loss in wellbeing from working in more hierarchical organisations.

On the other hand, Paul Frijters argues that although workers’ wellbeing is likely to be higher in flatter organisations, bigger and more hierarchical organisations are probably better suited and more successful at lobbying government for lower taxes and higher subsidies than smaller and flatter organisations. As a result, the prevailing tax and subsidy mix is probably tilted against flatter and smaller organisations.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- The World Wellbeing Panel on wellbeing and organisational structures is available here. The experts, their affiliations and their responses to the survey are here.

- The post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Hierarchy, by steinchen, under a CC0 licence

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy.

Nattavudh (Nick) Powdthavee holds a joint position as a Professorial Research Fellow at the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economics and Social Research, University of Melbourne, and a Principal Research Fellow in the WellBeing research programme at the Centre for Economic Performance at the LSE. He obtained his PhD in Economics from the University of Warwick in 2006 and has held positions at the University of London, University of York, and Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. He is the author of the popular economics book The Happiness Equation: The Surprising Economics of Our Most Valuable Asset. Click here for his website.

Nattavudh (Nick) Powdthavee holds a joint position as a Professorial Research Fellow at the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economics and Social Research, University of Melbourne, and a Principal Research Fellow in the WellBeing research programme at the Centre for Economic Performance at the LSE. He obtained his PhD in Economics from the University of Warwick in 2006 and has held positions at the University of London, University of York, and Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. He is the author of the popular economics book The Happiness Equation: The Surprising Economics of Our Most Valuable Asset. Click here for his website.

Paul Frijters is the newly arrived director of the Wellbeing Programme at LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance, taking over from Professor Richard Layard. Paul also heads the World Wellbeing Panel. He did his PhD on welfare and wellbeing in Russia, after a Masters in Econometrics. He has worked in a variety of roles on very different problems, such as urban-to-rural migration in China (where he headed a large international research program), corruption, applied econometrics, and wellbeing. He was voted ‘best economist under 40’ by the members of the Economic Society of Australia in 2009-2011. His works have been discussed in the New York Times, Washington Post, the BBC, etc.

Paul Frijters is the newly arrived director of the Wellbeing Programme at LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance, taking over from Professor Richard Layard. Paul also heads the World Wellbeing Panel. He did his PhD on welfare and wellbeing in Russia, after a Masters in Econometrics. He has worked in a variety of roles on very different problems, such as urban-to-rural migration in China (where he headed a large international research program), corruption, applied econometrics, and wellbeing. He was voted ‘best economist under 40’ by the members of the Economic Society of Australia in 2009-2011. His works have been discussed in the New York Times, Washington Post, the BBC, etc.