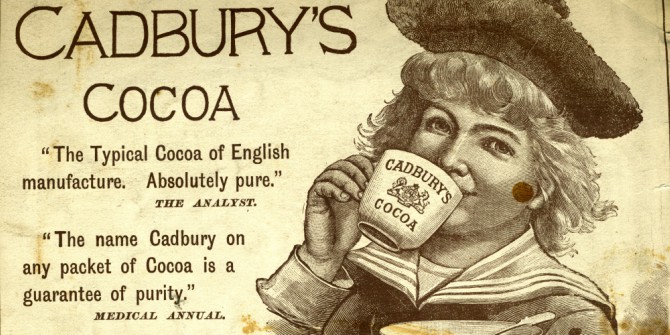

Endorsement and certification of brands have hit the mainstream, being used by both small firms and large multinationals in multiple product categories. Even old established global brands, such as Cadbury Dairy and Kit Kat chocolate created by Quaker businesses, are being offered with a certification label – the Fairtrade label. But what purpose do these certification labels serve? Who are they benefiting? When did this practice develop?

The Fairtrade label has two main aims: to help marginalised suppliers of raw materials in the developing world move from a position of vulnerability to one of security and economic efficiency; and to mobilise consumers in the developed world to make purchasing decisions based on trust and charity, relying on the direct certification of products by trusted third parties. The Fairtrade certification label is associated with the Fair trade movement which developed from the 1970s.

Very few earlier forms of fair trade are known, with the exception of the boycott of slave-produced sugar from 1791 where British Quakers, as part of the abolitionist movement, which encouraged consumers to switch from sugar to honey or to buy sugar from the East Indies, which was free from slavery. This research draws on the two principles used in fair trade — concerned with improving lives in developing countries, and with mobilising consumers in the developed world — to investigate earlier forms of fair trade in the developing world, and also the endorsement practices of brands in the developed world before the 1970s.

Quakers were Christian puritans that dissented from both the Roman Catholic Church and the established Church of England. Despite being a minority of the population, they dominated business in the eighteenth century, and were behind many of the great innovations which led to the industrial revolution. Before the twentieth century, the business and management practices of British Quaker businesses were more advanced than other companies. They considered that wealth for its own sake was a sin, and work for its own sake a virtue and an end in itself; products had to be beneficial and useful to society and of good quality; prices had to be fixed and fair; and delivery dates had to be respected.

In late nineteenth century Britain, Quaker chocolate firms such as Cadbury, Rowntree and Fry, the industry leaders, started procuring raw materials (cocoa, sugar, and gum arabic) directly from African countries rather than using intermediaries to ensure that the raw materials were free of slave labour. They found out that there was still slave labour being used in some countries. After multiple attempts to use diplomacy to stop slave labour from countries such as São Tomé e Príncipe from where they procured most of their cocoa, they stopped all imports from that market, and lobbied competitors to do the same. They then developed alternative cocoa production industries in other markets such as Gold Coast (renamed Ghana in 1957) and Cote D’Ivoire, contributing to the long-term economic development of those countries. Additionally, they created alliances in foreign markets and collaborated with local governments and planters, to help introduce new plantations and new farming techniques.

Cadbury, Rowntree and Fry also built housing, schools, hospitals, villages and markets, and improved workers’ living conditions in developing countries earlier than most philanthropists. They also helped create fairer power relations in international value chains between producers and consumers of cocoa and other raw materials used in confectionery.

This research uses British newspapers published from the 1860s to the late 1960s (a total of 774 articles) as a proxy for consumer opinions about the brands, and does content analysis of those news. It focuses on the two leading chocolate producers during that period (Cadbury and Rowntree). The findings highlight that the two Quaker firms did not explicitly associate their brands with any certification label, their philanthropic work, or with the association of their owners with the Society of Friends. Nonetheless, the press written by third parties about these firms and their entrepreneurs made indirect associations between the firms and several Quaker principles such as quality, purity, peace and slavery, and also the affiliation of their owners with the Society of Friends, among other characteristics.

These news items informed consumers about Quaker businesses and the principles and ethos that governed their management. Consumers used this information as a form of indirect endorsement of the chocolate firms and their brands, just as the Fairtrade Organization today endorses the same brands, but in a direct and explicit form.

Indirect endorsement was particularly important in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century Britain when the market remained relatively unregulated, consumers showed relatively high levels of sophistication and education (in relation to other markets), and newspapers or other media played an important role in providing information about firms, the activities of their entrepreneurs, and their brands.

Despite not having made substantial investments in marketing in their early days, Cadbury and Rowntree were able to build long-term reputations for their chocolate brands. Once the chocolate industry became global, characterised by intense competition, it became difficult and costly for consumers to make informed decisions just by relying purely on publicly available information about the firms, their entrepreneurs, and the brands they owned. Marketing investments in the form of advertisement campaigns, or public relations, became more important in creating a differentiated image for the brands.

British chocolate firms, founded by Quaker entrepreneurs, are just one illustration that businesses have been caring at a distance and consumers have been expressing their ethical, social and political concerns for far longer than we think. While direct third-party endorsements such as the fair trade label provide an explicit way for consumers to identify products and brands associated with certain standards, indirect third-party endorsement of brands can be a cost effective alternative to differentiate products and increase trust. Indirect endorsement can be particularly useful in markets where consumers are educated and have good access to media, and also in periods characterised by uncertainty and lack of regulation, such as in times of crises in which, among other challenges, firms have to deal with constrained marketing budgets.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the author’s paper Building Reputation through Third-Party Endorsement: Fair Trade in British Chocolate, published in Business History Review 90 (Autumn 2016): 457-482.

- The post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Engraved images from the Boy’s own Paper, 1880s and 1890s, Public Domain

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy.

Teresa da Silva Lopes is a Professor of International Business and Business History at the Management School, University of York, Director of the Centre for the Evolution of Global Business and Institutions (CEGBI), and Head of the Marketing Group. She is the President of the Association of Business Historians (ABH), President Elect of the Business History Conference (BHC), and a member of the Council of the European Business History Association (EBHA). She received her PhD from the University of Reading and was a Post Doctoral Fellow at the Said Business School, University of Oxford. She also has an MPhil, MBA and Licenciatura from Universidade Católica Portuguesa. In the past she has been a Thomas McCraw Fellow at Harvard Business School, and a visiting scholar at the University of California Berkeley, Columbia University, and École Polytechnique in Paris. Teresa.lopes@york.ac.uk

Teresa da Silva Lopes is a Professor of International Business and Business History at the Management School, University of York, Director of the Centre for the Evolution of Global Business and Institutions (CEGBI), and Head of the Marketing Group. She is the President of the Association of Business Historians (ABH), President Elect of the Business History Conference (BHC), and a member of the Council of the European Business History Association (EBHA). She received her PhD from the University of Reading and was a Post Doctoral Fellow at the Said Business School, University of Oxford. She also has an MPhil, MBA and Licenciatura from Universidade Católica Portuguesa. In the past she has been a Thomas McCraw Fellow at Harvard Business School, and a visiting scholar at the University of California Berkeley, Columbia University, and École Polytechnique in Paris. Teresa.lopes@york.ac.uk