The UK referendum on EU membership in June 2016 represented a key moment for European integration, and one that academics and political observers are still seeking to understand and explain. In the days running up to the referendum, bookmakers and pollsters had predicted that the ‘remain’ side would win, and, afterwards, many observers were left puzzled about just who voted for ‘leave’ — and why.

In a new paper, we examine the Brexit referendum vote in great detail, using statistical analysis as a way to highlight which factors proved to be the strongest predictors of the ‘Vote leave’ share.

Though our findings establish correlations, not causation, they nonetheless underscore the many complex issues that surfaced in the ‘Vote Leave’ result. Key issues and findings include:

EU exposure and immigration

Surprisingly, and contrary to much of the political debate in the run-up to the election, we find that exposure to the EU in the form of migration, trade and EU transfers to UK regions has relatively little predictive power.

All factors relating to EU exposure together explain under 50 per cent of the variation in the leave vote share — much less than other factors we analysed. We find some evidence that the growth rate of immigrants from the 12 EU accession countries that joined the EU in 2004 and 2007 is linked to the ‘leave’ vote share.

This stands in contrast to migrant growth from the EU 15 countries or elsewhere in the world. It suggests that migration from predominantly Eastern European countries has had an effect on voters. We cannot identify the precise mechanism — whether the effect on voters is mainly economic through competition in the labour and housing markets, or it is the result of changing social conditions.

In a recent research paper, we study the causal impact of migration on the evolution of anti-EU voter preferences, which in turn correlate with support for Leave. We found, consistent with the present paper, a relatively modest but statistically significant association between immigration from Eastern Europe and growing anti-EU sentiment represented by support for UKIP across European Parliament elections between 1999 and 2014.

Fiscal consolidation

In the wake of the Global crisis, the UK coalition government brought in wide-ranging austerity measures to reduce government spending and the fiscal deficit. At the level of local authorities, spending per person fell by 23.4 per cent in real terms, on average, from 2009/10 until 2014/15. But the extent of total fiscal cuts varied dramatically across local authorities, ranging from 46.3 per cent to 6.2 per cent. It is important to note though that fiscal cuts were mainly implemented as de-facto proportionate reductions in grants across all local authorities. This setup implies that reliance on central government grants is ultimately a measure of deprivation, with the poorest local authorities being more likely to be hit by the cuts.

This makes it impossible to separate the effect of deprivation as such from the fiscal cuts (which hit those areas that were more deprived to begin with) when studying the ‘Vote leave’ support, and still very challenging when working with a sample capturing anti-EU sentiment over time across local authorities in the UK. With this caveat on the interpretation in mind, our results suggest that local authorities experiencing more fiscal cuts were more likely to vote in favour of leaving the EU. Given the nexus between fiscal cuts and local deprivation, we think that this pattern largely reflects pre-existing deprivation.

UKIP and Brexit support

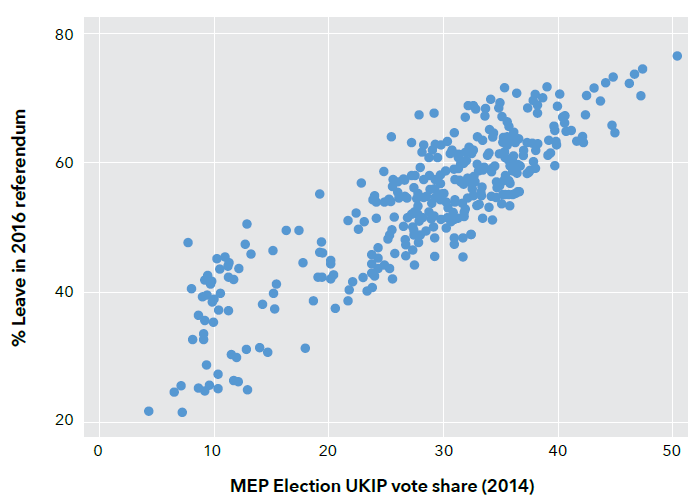

Our results indicate that electoral preferences as measured by the 2014 European parliamentary elections are strongly correlated with the Vote Leave share. In statistical terms, almost 92 per cent of the variation in the support for leave across local authority areas can be explained by the variation in vote shares for the 2014 European Parliament elections.

As figure 1 shows, the UKIP vote share is particularly important. We find that earlier parliamentary votes, especially the UKIP vote share, are extremely strong predictors of how voters in different local authorities voted in the EU referendum. Understanding the UKIP vote share therefore seems crucial for understanding the Brexit vote. Only founded in 1991 and taking on its current name in 1993, UKIP is a fairly new contestant on the British political scene. It has traditionally been seen as pushing the single issue of Britain leaving the EU. In the 2014 European Parliament elections it won the largest vote share, beating the Labour Party and the Conservative Party into second and third place. UKIP therefore has the ability to mobilise a large number of voters. But due to Britain’s first-past-the-post voting system UKIP is otherwise hardly represented in national UK politics. UKIP only has one Member of Parliament in the House of Commons and three representatives in the House of Lords. The relevance of UKIP for the referendum result and its dramatic rise, which has not been accompanied by representation in domestic politics, makes understanding the drivers behind UKIP’s ascent in recent years key to understanding the EU referendum result.

Figure 1

Socioeconomic characteristics

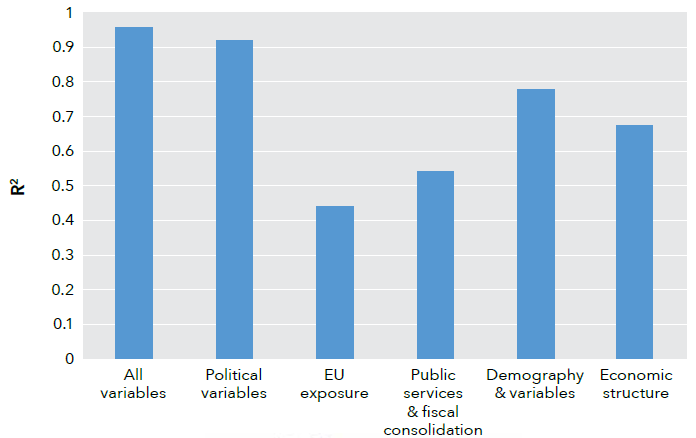

Figure 2 illustrates the predictive power of different sets of factors in explaining the referendum result and helps to shed light on the relative importance of different salient ‘issues’. For example, we find that demography and education (i.e. the age and qualification profile of the population across voting areas) explain just under 80 per cent of the leave vote share. The economic structure explains just under 70 per cent. Variables in this group include the employment share of manufacturing, unemployment and wages.

Figure 2

Context

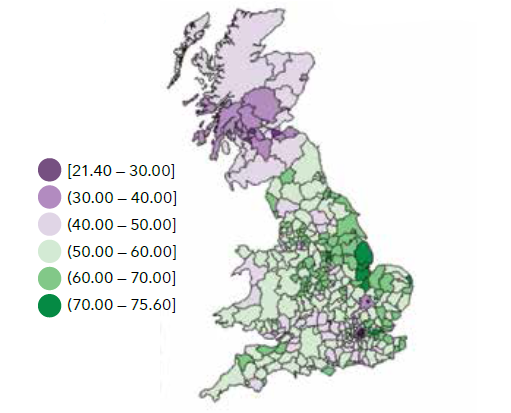

Our findings are based on analysis of the EU referendum result in England, Wales and Scotland across 380 local authorities and across 107 wards in four English cities. We relate the vote to fundamental socioeconomic features of these areas. Figure 3 plots the leave vote shares, measured as percentages, across the local authority areas (excluding Northern Ireland and Gibraltar). We stress that our analysis is looking at a rich set of correlations but cannot possibly identify which individual factors caused Brexit.

Figure 3

Additional related research (by Becker and Fetzer, referenced below) focuses on immigration from Eastern Europe as one specific factor of interest. Using more elaborate statistical techniques to understand whether migration was a causal factor in explaining UKIP’s rise, we find that UKIP gained significant support in areas that received a lot of migrants from Eastern Europe. However, given the complexity of voter behaviour, many more studies will be required to analyse other salient factors in the Brexit result in more detail.

Summary

The findings reveal important, and in some cases, surprising correlations. We find that exposure to the EU in terms of immigration and trade provides relatively little explanatory power for the referendum vote. Instead, we find that fundamental characteristics of the voting population were key drivers of the Vote leave share, in particular their education profiles, their historical dependence on manufacturing employment as well as low income and high unemployment.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post appeared originally at Advantage Magazine, published by CAGE, the Centre for Competitive Advantage in the Global Economy, an ESRC-funded research centre based in the Department of Economics at the University of Warwick.

- The post summarises the authors’ paper “Who Voted for Brexit? A Comprehensive District-Level Analysis, CAGE working paper 305/2016, and also refers to Does Migration cause extreme Voting?, CAGE working paper 306/2016, by Sascha O. Becker and Thiemo Fetzer.

- The post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Brexit, by TeroVesalainen, under a CC0 licence.

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

Sascha O. Becker is a professor of economics at the university of Warwick and research Director at the Centre for Competitive Advantage in the Global economy (CAGE.)

Sascha O. Becker is a professor of economics at the university of Warwick and research Director at the Centre for Competitive Advantage in the Global economy (CAGE.)

Thiemo Fetzer is an assistant professor of economics at the University of Warwick and a research associate at the Centre for Competitive Advantage in the Global economy (CAGE.)

Thiemo Fetzer is an assistant professor of economics at the University of Warwick and a research associate at the Centre for Competitive Advantage in the Global economy (CAGE.)

Dennis Novy is an associate professor of economics at the university of Warwick and a research associate at the Centre for Competitive Advantage in the Global economy (CAGE.)

Dennis Novy is an associate professor of economics at the university of Warwick and a research associate at the Centre for Competitive Advantage in the Global economy (CAGE.)