Place-based policies that target disadvantaged areas are widespread in both high-income and developing countries. Their impact depends crucially on the effective size of local labour markets. If labour markets are very local, an effective intervention needs to be targeted to the disadvantaged areas themselves and more distant interventions will not benefit the target group. If labour markets are not as local, targeted intervention is ineffective as it may simply benefit workers from other, more advantaged areas. A broader question concerns the incidence of local shocks to labour demand and their impact on labour mobility.

To answer such questions one needs a clear definition of a ‘place’. Most existing research on the topic and government statistical agencies divides geographical space into non-overlapping areas, which are assumed to be single labour markets. Examples would be the 367 Metropolitan Statistical Areas for the US, or the 320 Travel to Work Areas for the UK.

In such classifications, the cost of distance within areas is implicitly assumed to be zero. Because people commute large distances to work in the centre of big cities, large metropolitan areas are generally classified as single labour markets. But those who live in the northern suburbs might not think of the southern suburbs as part of their labour market. Second, the non-overlapping nature of labour markets constructed in this way causes inevitable discontinuities around the boundaries. Someone living just inside a large metropolitan area would be classified as living in a large labour market, while someone living just across the border would be classified as living in a modestly-sized labour market. However, these individuals live in essentially the same labour market.

The root of these problems is a failure to recognise the continuous nature of geographic space. In reality, the economy cannot be divided into non-overlapping segments, and there is always some commuting across borders. Typically, the labour market for one individual at one location overlaps with that for a second individual at a different but not too distant location, whose labour market then overlaps with that for a third individual, whose labour market may not overlap at all with that of the first individual. In recent work we show that if geographic space is treated as continuous, as opposed to a collection of non-overlapping units, one can attain a more realistic characterisation of local labour markets, with implications for the evaluation of local policies.

In our approach, a ‘local labour market’ represents the set of jobs that an unemployed worker, currently in a particular location, will apply for, and its size is determined by the cost of distance, measured as geographic distance, commuting time, or commuting cost. If the cost of distance is high, workers will be more reluctant to consider jobs at more distant locations than if such cost is small. This approach means that the boundary of a local labour market is fuzzy.

Jobseekers decide whether to apply to job vacancies at different locations, based on the probability of success, in turn affected by how many other jobseekers are applying to these jobs, and on the utility enjoyed on the job, depending on the distance to it and the wage paid. Linkages across areas arise because the number of applicants to jobs in a given area is likely to be influenced, even if only slightly, by unemployment and vacancies in other areas, as they are ultimately linked through a series of overlapping markets.

Data on the filling of vacancies allow us to infer the distance over which people look for work, as the ease to fill a vacancy in a certain area responds to the number of jobseekers for whom the vacancy is in their local labour market. If the vacancy filling rate in area A responds is to the number of jobseekers in area B but not in area C, we conclude that A is in the local labour market for residents of B but not for residents in C.

We use unemployment and vacancy data on 8850 Census wards in England and Wales, and combine these with micro data on wages and the use of transport modes to model commuting costs between any two wards. Our estimates show evidence of high costs of distance. For example, the probability of a random job 5km distant being preferred to random local job is only 19 percent. We also find that workers are discouraged from applying to jobs in areas where they expect relatively strong competition from other jobseekers.

Our work provides a useful toolkit to understand the likely impact of place-based policies. High estimated costs of distance may suggest that local intervention would have heavily concentrated effects on target areas. But this argument is deceptive if labour markets are overlapping: even though the labour market for an individual worker may be quite local, a local shock sends a ripple effect through surrounding areas, diffusing its impact over a much wider area than the typical commute. The extent of the ripple effect may be limited by “firebreaks”, i.e. natural or institutional borders across which few workers commute.

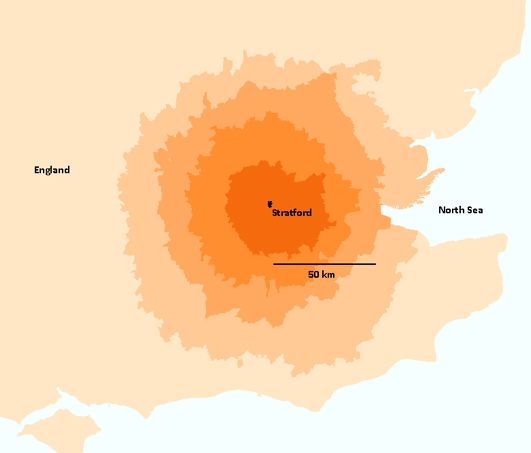

As an example, we consider an increase in the number of job openings in Stratford in East London, which was the main venue of the 2012 Olympics, and has an unemployment to population ratio about three times the national average – we thus combines a large rise in labour demand from Olympic-related projects with a disadvantaged local labour market. The rise in job openings predicts only a tiny (0.4%) increase in the local job finding rate, because unemployed workers living relatively close to Stratford divert some of their job search effort from their local wards towards Stratford. This raises job competition in Stratford, reduces job competition in their local wards, attracts applications from elsewhere, and so on. The bottom line is that even strong local stimulus has a limited bite on the local outflow rate from unemployment, because a series of spatial spillovers dilutes any local shock across space. (see Figure 1). This prediction is confirmed by actual labour market trends in and around Stratford: while vacancy data record a sharp rise in Stratford in the run-up to the 2012 Olympics, there is hardly any increase in job finding in Stratford or surrounding areas as a result of the spike in vacancies.

Figure 1. Effect of a localised labour demand shock on the unemployment outflow in surrounding areas

Notes. Data measure the percentage increase in the unemployment outflow, following a doubling of the number of vacancies in Stratford.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the authors’ paper How Local Are Labor Markets? Evidence from a Spatial Job Search Model, American Economic Journal, October 2017

- The post gives the views of its author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Commuters (Stratford East), by Ben Pugh, under a CC-BY-2.0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

Alan Manning is Professor of Economics in the Department of Economics and Director of the Community Programme at the Centre for Economic Performance at LSE. His research generally covers labour markets, with a focus on imperfect competition (monopsony), minimum wages, job polarisation, immigration, and gender. On immigration, his interests expand beyond the economy to issues such as social housing, minority groups, and identity. Alan holds a DPhil in Economics from Oxford University. For more on Alan’s work, visit his personal website.

Alan Manning is Professor of Economics in the Department of Economics and Director of the Community Programme at the Centre for Economic Performance at LSE. His research generally covers labour markets, with a focus on imperfect competition (monopsony), minimum wages, job polarisation, immigration, and gender. On immigration, his interests expand beyond the economy to issues such as social housing, minority groups, and identity. Alan holds a DPhil in Economics from Oxford University. For more on Alan’s work, visit his personal website.

Barbara Petrongolo is Professor of Economics at Queen Mary University, Director of the CEPR Labour Economics Programme and Research Associate at the Centre for Economic Performance of the LSE. Her main area of interest is labour economics. She has worked extensively on the performance of labour markets with job search frictions, with applications to unemployment dynamics, welfare policy and interdependencies across local labour markets. She has also carried out research on the causes and characteristics of gender inequalities in labour market outcomes, in a historical perspective and across countries, with emphasis on the role of employment selection mechanisms, structural transformation, and interactions within the household.

Barbara Petrongolo is Professor of Economics at Queen Mary University, Director of the CEPR Labour Economics Programme and Research Associate at the Centre for Economic Performance of the LSE. Her main area of interest is labour economics. She has worked extensively on the performance of labour markets with job search frictions, with applications to unemployment dynamics, welfare policy and interdependencies across local labour markets. She has also carried out research on the causes and characteristics of gender inequalities in labour market outcomes, in a historical perspective and across countries, with emphasis on the role of employment selection mechanisms, structural transformation, and interactions within the household.