There is a lot of talk about the future of work with developments such as AI, telecommuting, and the gig economy making headlines. Techno-utopianists fantasize about a future where manual labour is obsolete; economic innovators dream of the transformative nature of a basic minimum wage; and, entrepreneurs promote new workplace models. Such changes propel us into a future with modalities and products that may seem wildly innovative, but still –deceptively –maintain financial flows and economic structures locked in Gilded Age-thinking and approach. We are creating shiny new tools to continue a way of work rooted in inequity, white supremacy, extractive economic structures, and a disconnection from our ecological ecosystems.

Why do we keep repeating history and remain stifled with unimaginative progress? Although such trends represent significant shifts worthy of careful consideration, they fail to offer a forward-thinking methodology to deeply transform the way the world ‘works’. To echo Einstein –“No problem can be solved with the same level of consciousness that created it” –thorough and imaginative innovation cannot be created with the same methods and ways of thinking that reinforce our current paradigm. We might work from home or AI tools may become ubiquitous, but if our fundamental ways of ‘doing’ and ‘being’ with one another are not radically reinvented, then we can expect a future that, in fact, looks much like our present in the ways that matter most.

Our three-year interdisciplinary research study explores methods for building a different kind of future –one that outperforms the status quo, blows the top off ‘innovation as usual’, and offers outcomes that buck the trends of history to create a thriving, resilient economy that works for all. We have scoured urban planning, organisational design, education, public health, high-tech, and other fields, looking for solutions that broke the mould of what outcomes were deemed plausible. We find companies and organisations that intentionally involved more and, crucially, different voices in the creative process of solutions, products or outcomes, achieved very different results than their peers.

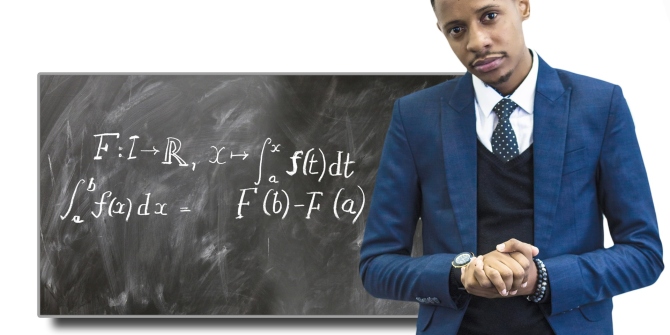

Over the past two decades, Silicon Valley has sparked a sea change in the ways products and services are brought to market – moving away from a closed-door, top-down process and towards a crowdsourced, consumer-driven model in which end-users help shape and create the products they utilise. Companies – across sectors – have come to recognise that regularly engaging end-users to test assumptions and generate insights, gives them an edge over their competition from a profit perspective. Industry articles commonly note that every dollar spent on end-user involvement generates $2 to $100 in return.

Furthermore, companies and organisations that open up not only their creative processes but also their decision-making processes to more and different voices, achieve transformative outcomes. In our research, examining more than 70 such organisations and companies, we find their ways of practicing such co-creative work to be strikingly consistent, implying that there are pathways to follow to foster more deeply imaginative innovation.

We have come to call these results ‘breakout innovation’, defined as having three primary characteristics: powerful alignment with the needs and possibilities of the system they are addressing; solution delivery that makes a rapid leap from concept to real-world implementation which has wide uptake; and generating of a shift in power that activates more innovators, permanently changing dynamics. For example, 9,000 New Orleans residents serving as researchers, designers, and ultimately decision makers in a recovery framework post hurricane Katrina; or, a patient-powered research network enabling heart disease patients to collaborate with fellow patients as well as researchers, doctors, and other health providers on advancing heart disease research.

However these examples are the exception. There is often a (self-imposed) limit on how far people are willing to extend the practice of co-creation; that line is the boundary of where decision-making authority, power, and wealth is shared. As journalist Scott Rosenberg writes, “Once whole worlds can be simulated for the senses, the only way to assure the integrity of the public imagination will be to get the power to create those worlds out of the hands of an elite and into general circulation.” Or, as, William Gibson explains it: “The future has arrived — it’s just not evenly distributed yet.” We believe inequality in the power to influence –such as, through decision-making authority –although rarely spoken about, has vast underlying impact.

Through our research, we document a phenomenon called “end-user exclusion:” systematic exclusion of input from the people that products, solutions or initiatives directly affect and/or of which they are the intended the beneficiaries/end-consumers. Our interviewees’ responses suggested there is an entrenched belief system that only certain groups of people –with a certain kind of education, privilege, and access –have the expertise and ability to generate smart solutions. Unfortunately, this consolidation of influence is the operating methodology of our present day systems. For generations, many have contributed labour and creative capacity without commensurate control over outcomes, a stake in decision-making, or ownership of the results.

The exclusion of the majority of the world’s ingenuity has huge costs. We are stifling the innovation that an aggregate, integrated community could provide. There are immeasurable consequences to not listening to the majority of the world’s –or our country’s or town’s –wisdom. If we don’t listen from everywhere, if we don’t include and engage a preponderance of voices, we not only get poorer results and make avoidable mistakes, we invent a future of work that is encoded with the same deep and systemic societal pathologies. In other words, we continue to have outcomes in alignment with the status quo that actively do harm –such as systemic racism, war, climate change, sexism, and femicide.

We must update our methods in order to create a future of work that works for all. To create a thriving, beautiful, and more just existence on earth we must flip the paradigm that has institutionalised the exclusion of the worth, ingenuity, creativity, and leadership of most of the world. As Wendell Berry reminds us in Faustian Economics, the real way toward a future new in its resilience is by learning again “…how we can make the most of what we are, what we have, what we have been given.”

What we have is: all of us.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- The post gives the views of its author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Photo by “My Life Through A Lens” on Unsplash

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

Joanna Cea is a Visiting Scholar at Stanford University’s Global Projects Center and the Director of Buen Vivir Fund at Thousand Currents. She is an advocate, facilitator, and researcher for investment that honours our earth and human rights.

Joanna Cea is a Visiting Scholar at Stanford University’s Global Projects Center and the Director of Buen Vivir Fund at Thousand Currents. She is an advocate, facilitator, and researcher for investment that honours our earth and human rights.

Jess Rimington is a Visiting Scholar at Stanford University’s Global Projects Center. She is a strategist for social change organisations and movements, with a focus on the methodologies, processes and ethics of a new/next economy. www.jessrimington.org

Jess Rimington is a Visiting Scholar at Stanford University’s Global Projects Center. She is a strategist for social change organisations and movements, with a focus on the methodologies, processes and ethics of a new/next economy. www.jessrimington.org

Some excellent points here. There’s often a lot of conflict between the drive for innovation and more fundamental concerns like “how to turn a profit” which is where the borders start to get harder. Quite a lot of friction is falling out of the challenge in reconciling innovation for personal growth vs innovation from a business perspective so this is definitely an area to watch. Influencers like Whitney Johnson often discuss the idea of self-innovation and disruption, but the majority of business-driven “innovators” will focus more on how innovation is almost solely required to grow the bottom line.