In a recent study, we investigate the role that culture and institutions play in creating gender differences in willingness to compete. We compare the competitiveness of women growing up in different periods in the recent history of mainland China and Taiwan. We find that women in Beijing who grew up during the communist regime, when gender equality was emphasised, are more competitively inclined than their female counterparts who grew up during the post-1978 reform era. These women are also more competitively inclined than their counterparts in Taipei.

The results suggest that strongly supported policies of gender equity can have a significant impact on individual behaviour.

Our research strategy was to conduct laboratory experiments in Beijing and Taipei , in order to compare the competitive preferences of men and women growing up under two distinct regimes, communist and non-communist. While each society originated from the same Confucian values, they experienced a radically different history from 1949.

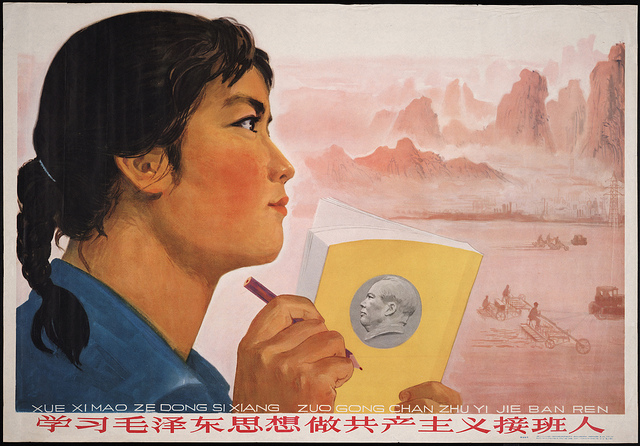

From 1949, mainland China experienced a series of dramatic changes in its social and economic institutions. During the first 30 years (1949-1977), the ruling communist party – guided by Marxist ideology – implemented a centrally planned economy. Within a short period, mainland China denounced old Chinese culture and established new social norms. In those years, especially during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), women’s position in society was strongly promoted, while the Confucian ideology that women are subordinate to men was vilified.

Chinese propaganda poster, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, UofT, under a CC-BY-2.0 licence

Chinese propaganda poster, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, UofT, under a CC-BY-2.0 licence

- The 1958 birth cohort who spent all their school years in the period of the Cultural Revolution.

- The 1966 birth cohort who spent three primary school years in the period of the Cultural Revolution and the rest in the reform era.

- The 1977 birth cohort who spent their formative years entirely in the reform era (when China started switching from a communist culture to a more market-dominated individualistic culture in 1978).

To control for the potential counterforce – induced over time by expanding education and market domination and greater awareness of gender equality – we conducted the same laboratory experiments with Taiwanese subjects born in the same years. Taiwan was subject to the same Confucian traditions and went through significant economic growth. But it was not subject to the ideological transformation experienced by mainland China.

We measured competitive preferences using a well-established procedure, whereby participants had to complete as many additions as possible of sets of two-digit numbers in five minutes. These were done under different payment mechanisms (piece rate or tournament), and participants were asked, in a subsequent round, to choose between a piece rate and a tournament.

Our findings confirm that exposure to different institutions and norms during crucial developmental ages significantly affect individuals’ behaviour. In particular, women in Beijing growing up during the communist regime are more competitively inclined than their male counterparts; they are more competitively inclined than their female counterparts growing up during the market regime; and they are more competitively inclined than their female counterparts in Taipei. For Taipei, there are no statistically significant cohort or gender differences in willingness to compete.

These results – which control for other factors – confirm that exposure to different institutions and social norms during crucial developmental ages changes individuals’ behaviour. Moreover, exposure to a strong gender equality message for a relatively short period can change women’s willingness to compete. To the extent that today’s world has embarked on a journey to defy the old gender order, this finding has policy implications, since it suggests that strongly supported policies of gender equity can affect individual behaviour.

Finally, to see if there is a feedback effect from the regime to attitudes, we asked in an exit survey if subjects in our experiment believed the government should reduce income inequality and if they supported less government intervention in the economy. We found that mainland Chinese women relative to Taiwanese were more likely to support government intervention to reduce inequality and also more likely to support government intervention in the economy. The same result was found for mainland men. From this we conclude that Communist propaganda has a long lasting effect on individuals’ attitudes.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the paper Gender Differences in Willingness to Compete: The Role of Culture and Institutions, forthcoming in the Economic Journal and presented at the Royal Economic Society’s annual conference at the University of Sussex in Brighton in March 2018.

- The post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Photo by Baron Reznik, under a CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy

Alison Booth is a professor of economics at the Research School of Economics, Australian National University, Australia.

Alison Booth is a professor of economics at the Research School of Economics, Australian National University, Australia.

Elliott Fan is an associate professor at the Department of Economics, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Elliott Fan is an associate professor at the Department of Economics, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Xin Meng is a professor of economics at the Research School of Economics, Australian National University, Australia.

Xin Meng is a professor of economics at the Research School of Economics, Australian National University, Australia.

Dandan Zhang is an associate professor at the National School of Development, Peking University, PR China.

Dandan Zhang is an associate professor at the National School of Development, Peking University, PR China.