In many OECD countries, economic growth has yet to recover the lost ground suffered in the aftermath of the financial crisis. In some of them, unemployment has been persistently high, investment rates disappoint, and productivity is extremely sluggish – a “low growth trap”.

Put differently, all three sources of sustainable long-run growth under-perform. This jeopardises societies’ ability “to make good on their promises to current and future generations – to create jobs and develop career paths for young people, to pay for health and pension commitments to old people”. (OECD, 2016).

While this partly reflects the persistent weakness of demand in some cases (Mann, 2016), there are policy tools available that affect the long-run productive capacity of the economy, or potential growth. Our recent work takes a fresh view on the relative payoffs in terms of raising future growth. We study how various product and labour market policies and regulations affect per capita income growth over different horizons and through the three supply-side channels: multi-factor productivity (MFP), capital deepening and employment.

Sizeable effects on per capita income of product and labour market regulations and policies

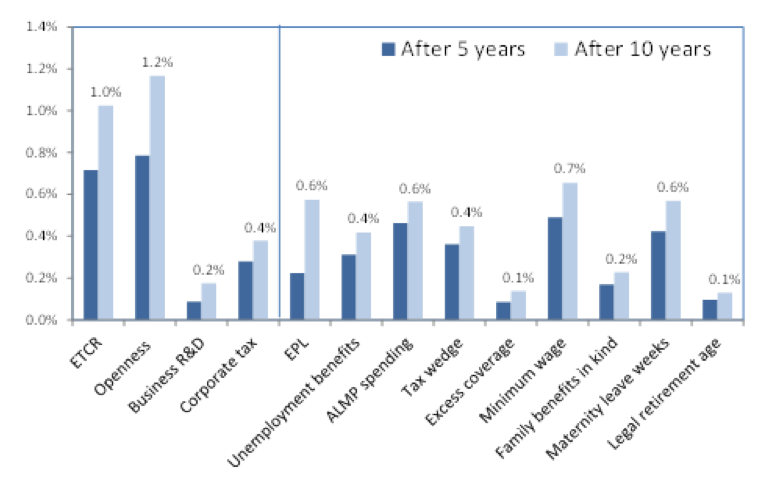

We find that product market regulation (PMR) reforms have the largest overall direct policy impact: reducing regulatory barriers to competition induce a cumulative increase of 0.7 per cent of GDP per capita over a 5-year horizon. Other policies with considerable overall effects include increased spending on active labour market policies (ALMPs), a reduction in labour tax wedge, in the minimum wage or in the length of maternity leave with impacts ranging from 0.3 to 0.5 per cent. Typical reforms in other policy areas tend to have a smaller impact on per capita income (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The impact of reforms on GDP per capita, 5 and 10 years after the reforms

Notes: Typically observed reforms are measured here by the average of all beneficial two-year policy changes that were observed over two consecutive years in the sample

Effects of policies transit through different supply-side channels

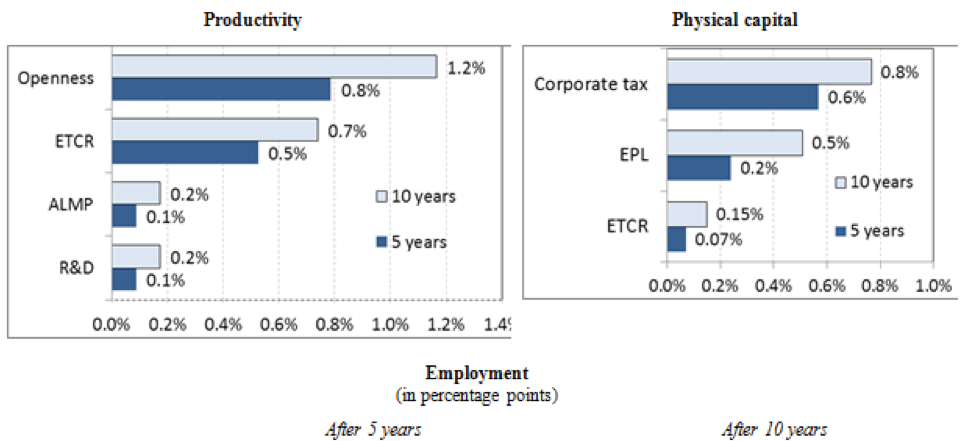

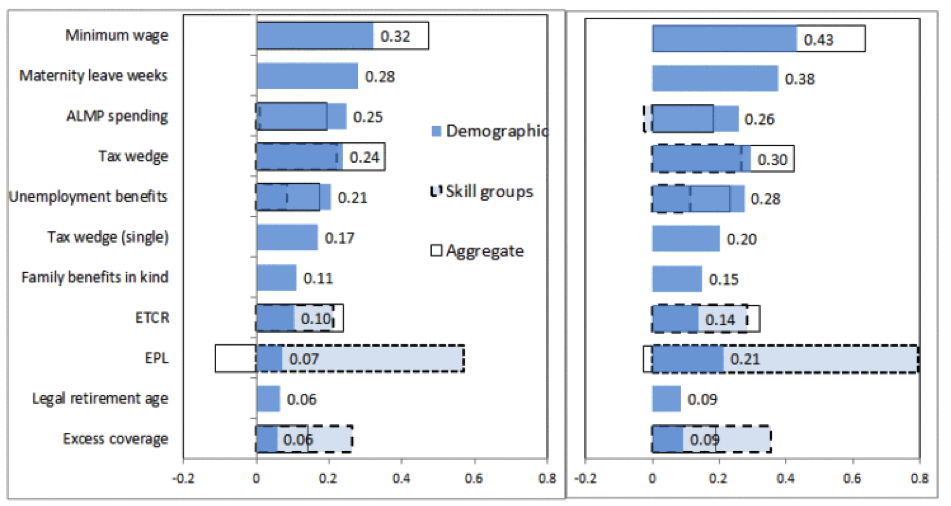

Different policies have different impacts on the separate supply-side components. For instance, PMR affects each of them, while labour market policies tend to impact only employment. Exceptions are ALMPs, which affects both productivity and employment, and EPL, which drives both capital deepening and employment. Finally, the corporate tax has an effect only on capital deepening, while R&D affects only productivity (Figure 2).

Long-term effects materalise slowly in some cases

The policy effects differ over longer horizons. For instance, the overall long-term effects on GDP per capita of PMR, employment protection (EPL) and ALMP spending are considerably larger than the 5-year impacts. This is mainly due the fact that MFP and capital are slower to react to reforms, compared to employment (Figure 1).

Possible extensions

These results are based on past policy changes and assume that the impacts are uniform across countries and various institutional settings. But the estimation results shown in Figures 1 and 2 could be used as a starting point to provide precious help for policy makers for the elaboration of comprehensive structural reform packages. Depending on the ease with which reforms can be implemented, policies could be picked to reach policy objectives in terms of overall impact on per capita income. A natural follow-up to our paper would be to extend it to take into account country specificities and differences in the initial policy and institutional settings. Also, the enriched framework could be used to build an interactive policy simulator, which would help policy-makers to figure out the impact of planned reforms and to design comprehensive policy packages to achieve objectives such as a given increase in per capita income over a given horizon.

Figure 2. Effects of improving structural policies (predicted effects of typically observed reforms* in each policy area)

Note: *Typically observed reforms are measured as the average improvements in the policy indicators over all two year windows that show improvements in both periods (see Table 5, column 4). The employment rate effects use all three aggregation approaches, and the size of the effects is indicated by numbers for the aggregation using demographic groups. See details in Egert and Gal (2018)

Conclusion

This chapter described and discussed a new simulation framework that quantifies the impact of structural reforms on per capita income. Compared to earlier attempts, the new framework developed in this chapter broadens the range of quantifiable reforms, updates the underlying empirical relationships, covers the post-crisis period, and improves the framework’s internal consistency. The chapter presents the new coefficient estimates on the three main supply-side components (MFP, capital, and employment). The chapter is a step in a gradual, ongoing process to continuously improve and update the quantification of the effect of structural reforms on per capita income levels. Further work is needed to better account for country-specific effects and to extend the analysis to emerging market economies. Last but not least, the extent to which the macroeconomic estimates are consistent with results obtained on the basis of sector- and firm-level data will be verified in future work.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the authors’ article The quantification of structural reforms in OECD countries: a new framework, Chapter 7 in Campos, de Grauwe and Ji (eds.), Structural Reforms in Europe.

- The post gives the views of its author, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Photo by Ron Reiring, under a CC-BY-2.0 licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

Balázs Égert is a Senior Economist at the OECD’s structural surveillance division. He previously worked at the Austrian Central Bank (2003-2007). He was visiting researcher at the South African Reserve Bank (2007), Bruegel (2006), CESifo (2006), the Czech National Bank (2006), the central bank of Hungary (2005), the Bank of Finland/BOFIT (2004/2005) and the Bank of Estonia (2002). He earned his PhD at the University of Paris X-Nanterre (2002).

Balázs Égert is a Senior Economist at the OECD’s structural surveillance division. He previously worked at the Austrian Central Bank (2003-2007). He was visiting researcher at the South African Reserve Bank (2007), Bruegel (2006), CESifo (2006), the Czech National Bank (2006), the central bank of Hungary (2005), the Bank of Finland/BOFIT (2004/2005) and the Bank of Estonia (2002). He earned his PhD at the University of Paris X-Nanterre (2002).

Peter Gal is an economist at the OECD’s economics department, working on micro- and macroeconomic aspects of productivity, labour markets and the role of structural policies. Previously he worked at the International Monetary Fund, the Central Bank of Hungary and in other areas of the OECD. He holds a PhD and an MPhil in Economics from the Tinbergen Institute in Amsterdam and a university degree in Economics from the Corvinus University of Budapest.

Peter Gal is an economist at the OECD’s economics department, working on micro- and macroeconomic aspects of productivity, labour markets and the role of structural policies. Previously he worked at the International Monetary Fund, the Central Bank of Hungary and in other areas of the OECD. He holds a PhD and an MPhil in Economics from the Tinbergen Institute in Amsterdam and a university degree in Economics from the Corvinus University of Budapest.