The Blitz lasted from Sept 1940 to May 1941, during which the Luftwaffe dropped 18,291 tons of high explosives and countless incendiaries across Greater London. Although these attacks have now largely faded from living memory, our recent paper shows that the impact of the Blitz remains evident to this day in both London’s physical landscape and economy.

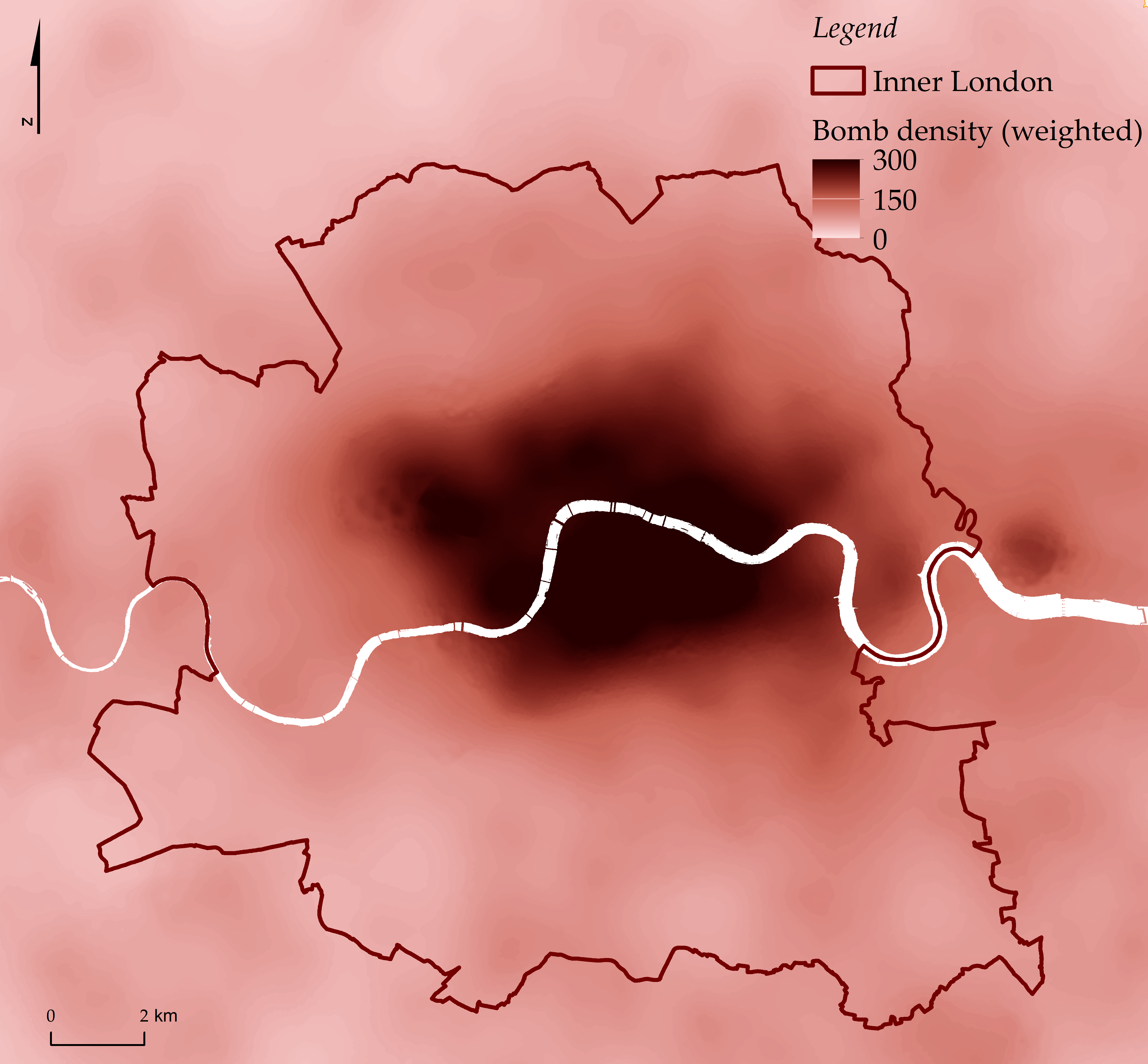

Using recently digitised National Archive records on the locations of all bombs dropped during the Blitz (see Figure 1 below), we compare the locations of Blitz bomb strikes with local differences in London’s modern-day building heights, employment levels, and office rental prices. After controlling for the concentration of bombs in the centre of London, we find that areas that were more heavily bombed during the Blitz now have more permissive development restrictions due to the fact that fewer historic buildings in such areas survived. Consequently, these areas also have built more office space and have higher worker densities today.

Figure 1. Blitz bomb density

Consistent with considerable empirical evidence from other cities, the consequence of this higher worker density in London has been greater worker productivity (which we proxy with office rent levels). What is new about this research, however, is the magnitude of measured effects. Whereas previous research has primarily sampled secondary cities and has generally found that a doubling in worker density raises productivity by only about 5 per cent (as measured by wages), even after extensive sensitivity tests our paper shows an increase in London’s office rents of 25 per cent. We argue that this difference is largely due to London’s unique position as perhaps the world’s foremost financial and commercial centre, and the exceptional productivity and innovativeness of its resident population. Therefore, the benefits of greater worker density in London are likely to be exceptionally large.

City planners are tasked with controlling real estate development in order to mitigate negative externalities arising from incompatible land uses and costs of congestion such as traffic. However, these restrictions (especially building height limits) entail various costs, for example, higher property prices and greater price volatility. But equally significant is the fact that constraining worker density damages the productivity of the economy. For many historical reasons, London has one of the most restrictive planning regimes in the developed world. For instance, the average height of office buildings in its primary financial district (the City of London) is still only eight floors – still reminiscent of bygone days before the advent of steel building frames and lifts. Based on back-of-the-envelope calculations, we estimate that the value of the Blitz to London in reducing the restrictiveness of its current planning regime and permitting higher densities is £4.5 billion annually, equivalent to 1.2 per cent of London’s GDP.

Ideally, planners would calibrate the stringency of development controls to ensure that society makes the best trade-off between the costs and benefits of greater worker densities. However, in order to make this judgement, planners require accurate information on both these costs and benefits. What our research now shows is that for the case of London, and perhaps other global cities such as New York and Tokyo, the benefits of greater worker density appear to be much larger than anyone had previously surmised. Consequently, if welfare maximisation is indeed city-planners’ primary goal, then, at least in those cities, planners should now be reviewing the stringency of their height restrictions and new development controls more generally.

Spurred on by the critical and commercial success of trophy architect Norman Foster’s ‘Gherkin’ in 2004, London’s planners have however become increasingly willing to approve taller structures. Only a few short years ago London possessed just several dozen buildings it defined as ‘tall’ (with more than 20 floors), but planners have since approved a total of 510 such buildings, 115 of which are presently under construction. While some might blanch at this rush of tall buildings, research shows that even the tallest buildings currently in London’s pipeline are still only a fraction of the size that would be necessary to equate supply with demand. Therefore, as much as London’s skyline has expanded in recent years, there is still considerable scope for increasing building heights and economic welfare across the city.

The Blitz was a tragic episode in London’s history, the likes of which one only hopes will never be repeated. However, by locally relaxing the restrictive planning regime put in place after the war, for all its human cost, the Blitz has subsequently had an extremely positive effect on London’s present day economy. Moreover, this lasting influence has now provided us with unique insights into the very human drivers of urban economics, and spotlights the exceptional dynamism of this enduring city.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the authors’ paper The Billion Pound Drop: The Blitz and Agglomeration Economics in London, Discussion Paper No 1542 of LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance.

- This post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: Photo HU 36157, by unknown author, from the collections of the Imperial War Museums, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

Gerard Dericks is senior lecturer in real estate economics and finance at Oxford Brookes University. Gerard received his PhD from LSE and recently completed a post-doc at the University of Oxford. He has industry experience as an analyst with Property Market Analysis LLP and research consultant with Policy Exchange. He was also a contributor to the winning submission for the 2014 Wolfson Economics Prize.

Gerard Dericks is senior lecturer in real estate economics and finance at Oxford Brookes University. Gerard received his PhD from LSE and recently completed a post-doc at the University of Oxford. He has industry experience as an analyst with Property Market Analysis LLP and research consultant with Policy Exchange. He was also a contributor to the winning submission for the 2014 Wolfson Economics Prize.

Hans Koster is an associate professor at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam’s department of spatial economics. He obtained his bachelor’s degree in economics at the Erasmus University Rotterdam and his master’s degree (cum laude) in spatial economics at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Hans is also a leading research fellow at the Higher School of Economics in St. Petersburg, a research fellow with the Tinbergen Institute, a research associate with LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance’s urban programme, and a research affiliate with the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR).

Hans Koster is an associate professor at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam’s department of spatial economics. He obtained his bachelor’s degree in economics at the Erasmus University Rotterdam and his master’s degree (cum laude) in spatial economics at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Hans is also a leading research fellow at the Higher School of Economics in St. Petersburg, a research fellow with the Tinbergen Institute, a research associate with LSE’s Centre for Economic Performance’s urban programme, and a research affiliate with the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR).

I must admit i am staggered by this. I make no comment on your substantive claims about economic development but to reference the Blitz like this is at best tasteless and at worst offensive!

The Blitz killed c40,000 people and maybe beas millenial academics you consider yourself sufficiently removed from the period to joke but as someone older and who lives in London i am not.

Somehow i doubt you would examine the Atlantic slave trade or the Holocaust in quite the same flippant manner.