One would be hard-pressed to find many commentators ready to say Europe’s manufacturing industry is coasting. Rather, the last decades have been quite competent at throwing several challenges towards our economic model. The 2018 European Trade Union Institute (ETUI) Conference “The World(s) of Work in Transition” managed to name a few: Climate change, demographic transitions, digitalisation, automation and finally the nexus of free movement of capital and services with globalisation.

Clearly, there is plenty to think about. However, especially these last two challenges are often accredited as being two of the main problems facing the European economy today. In fact, automation and globalisation are constantly linked with the squeezing of Europe’s manufacturing base, its workers and the rise of populism. Where the golden age of capitalism offered a safe middle-class existence to workers in manufacturing, these jobs now all seem to be either automated or off-shored. Does this mean we should roll the credits for these industries?

The squeeze

The general mechanism behind these challenges is, arguably, quite straightforward. Starting in the post-war era, the global economy has been steadily becoming more open and interlinked, creating competition for both companies and labour. This process went into second gear when China, India and the former Soviet Union entered the race during the 1990s.

In what Richard Freeman famously dubbed “The Great Doubling”, the size of the global labour pool increased massively from around 1.46 billion to 2.93 billion workers. As markets grew, European companies therefore started to face even stronger competition. While these firms generally had an edge in terms of quality, they faced stiff opposition on the level of prices. Allowing for a degree of oversimplification, this new dimension of globalisation confronted European companies with a fresh set of options to remain competitive at the global level.

On the one hand, processes such as the “Great Doubling” opened new avenues for off-shoring manufacturing jobs, a development which already had been well-established in the 1980s. Many Asian low-income countries have indeed managed to hoover up large numbers of manufacturing jobs in an attempt by firms to cut costs. On the other hand, this same growing competition helped the push towards technology as a means of increasing productivity and lowering prices. To give a clue, sales of multipurpose robots in the EU already topped 29,800 per year in 2000.

Finally, in some cases firms did not even have to resort to either option. Their mere existence often worked as a sword of Damocles dangling over labour’s head, depressing wages along the way. In short, in this brief and stylised version of the story, it was workers in manufacturing, often in the middle-class, that lost out.

Automation and the return of jobs?

The current debate on automation continues down this line, only in a more pessimistic way. Martin Ford, for example, is already sounding the alarm and warning us about a jobless future due to rapid technological change. More moderate positions, such as the one of Brynjolfsson and McAfee, however argue that adjustment will come in some form or another. We will have jobs, but different ones. But what if automation can also help us bring back employment in those industries we initially lost to off-shoring?

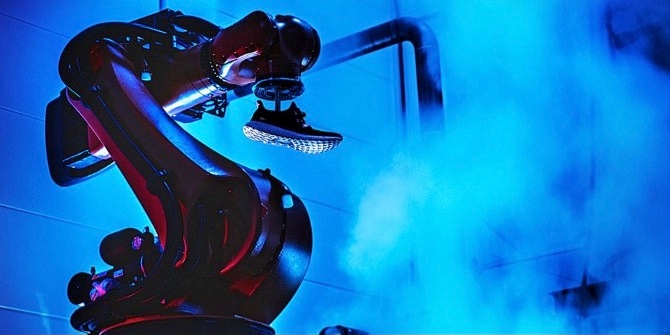

Take the case of Adidas, a classic story of a European company outsourcing much of its production to Asia. In fact, all of Adidas’ thirty largest suppliers in terms of worker employed are scattered throughout China, India, Indonesia, Vietnam and Bangladesh. Yet, this trend seems to have been bucked. In 2018 the company unveiled two new Speedfactories, one in Ansbach and another in Atlanta.

The aim of these new factories is to bring supply once again closer to demand, providing more agility at peak times. In time Adidas even hopes to produce 50% of its sales in this new speed programme. Clearly, the company is taking steps toward reshoring a chunk of its production as part of a broader trend of companies reconsidering the location of their production. The UK textile industry for example is projected to add some 20,000 jobs in the next five years, in large part due to reshoring.

Driving this wave are among other factors, rising wages (e.g. wages in Schenzhen have more than tripled in the last decade) and a growth in labour disputes in Asia. However, what really facilitates Adidas’ capacity to bring part of its production back to Europe and the US is technology. Its new Speedfactories are real marvels of engineering. Not only is the process almost fully automated, but the robots are also capable of flexible production and product customisation, all at three times the speed of Adidas’ other production lines.

Technological advancement paired with falling prices of robots drastically changes the cost-benefit analysis of off-shoring. What emerges is therefore a new avenue of technological reshoring of manufacturing jobs. Among all of the economic adjustment that could take place as a result of further automation, the return of industries lost in times past could well be one of them. Sure, they will look, smell, sound and act differently from before, but should provide employment, knock-on effects and overall surplus all the same.

Conclusion

European manufacturing faces a number of challenges. However, the dictum “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” could help us to disentangle a piece of the puzzle. As technology is becoming cheaper and more advanced, the cost-benefit analysis of off-shoring could well be changing away from further outsourcing. We might therefore continue to see a further trend of reshoring manufacturing back to Europe. While this process is of course not bringing back all of the jobs once lost (let alone at the same skill-level) it does at least offer one more avenue in which automation can directly create, as opposed to destroy, employment on the old continent.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post originally appeared at the LSE NETUF blog, and then at at LSE Europp,

- The post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image credit: A robot at the Adidas Speed Factory, Credit: Adidas

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

Toon van Overbeke is a PhD Candidate at the LSE’s European Institute.

Toon van Overbeke is a PhD Candidate at the LSE’s European Institute.