Professional firms have long been able to use technology to preserve the commercial value of their business model. From the electronic calculator to spreadsheet software, technological advances allowed these firms to streamline operations by delegating labour-intensive, low-value tasks to cheaper and more efficient machines.

However, the story of technology and professional work is about to change. A new generation of smart machines appears to threaten the core of the professional business model. Authors such as Richard and Daniel Susskind, and Clayton Christensen have delivered the templates for consultants, lawyers, and accountants to be worried about the automation of even high-value professional activities. In the new digital world, they argue, established professional firms find themselves competing with start-ups developing technology solutions that can make expertise more accessible to a broad audience, respond to unstructured tasks, and induce trust in transactions, eliminating the need for highly-trained professionals.

The mantra of ‘disrupt yourself or be disrupted’ is driving record investments by the Big Four (KPMG, EY, Deloitte and PwC) and other large professional firms into becoming digital innovators themselves. Dedicated technology teams oversee hundreds of projects to achieve technology-led change along every part of the audit, assurance, and advisory spectrum.

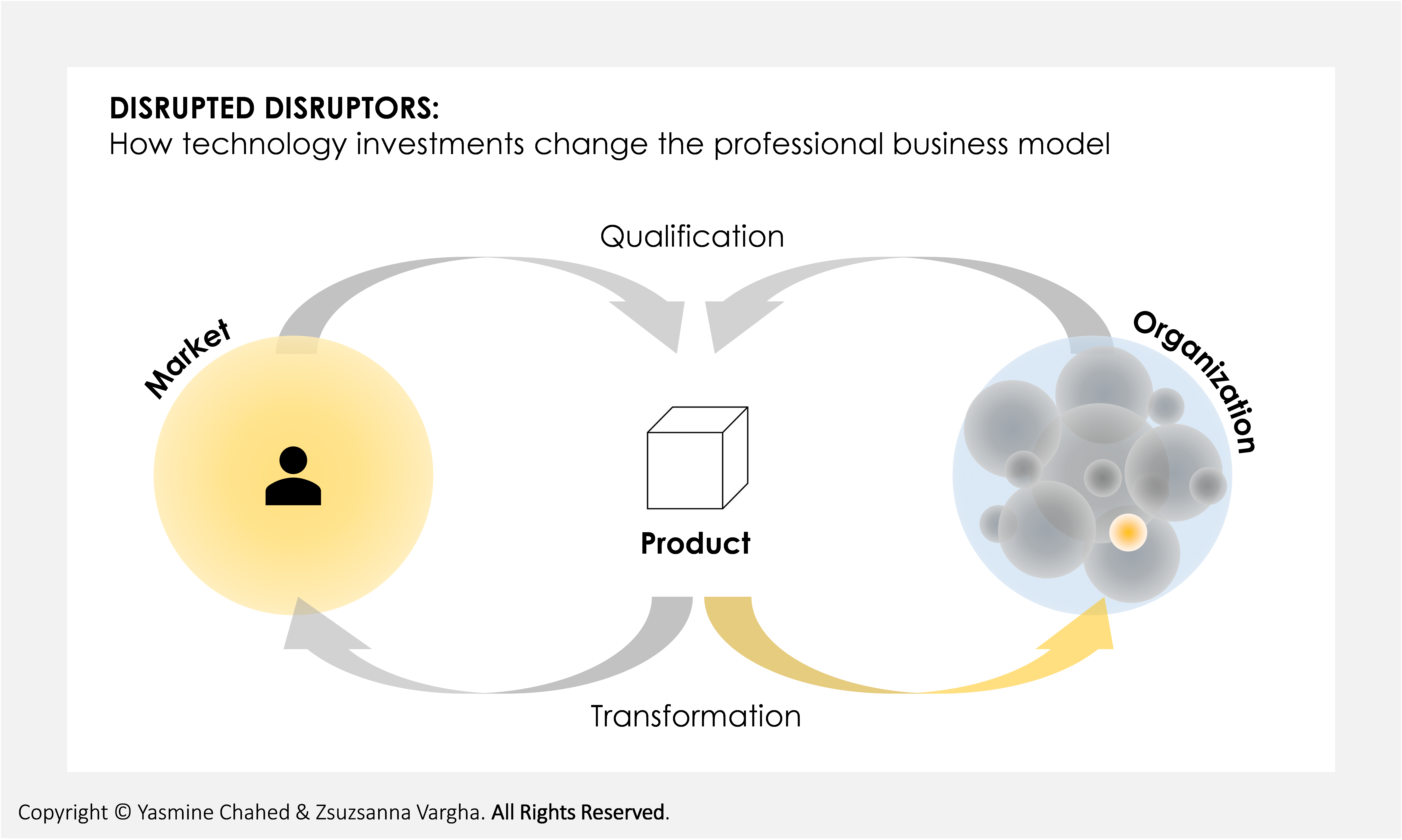

While everyone assumes that one must invest billions in technology to stay relevant, our research shows that the fundamental shift is to transform professional expertise into a product that has a stand-alone value to its users.

We observe a shift from the selling of billable hours to the selling of technology itself. When established professionals capture their knowledge and insight inside technology, building algorithms and analytics for clients, they create new objects. However, by doing that, can these professionals keep working the same way as they did before? We have to start out from the fact that the critical question for these experts now becomes, how to popularise their technology product — who will buy it and why? Here we can draw on the interdisciplinary literature on marketisation, which has studied extensively the process by which objects are turned into products that circulate in markets.

Theories of product qualification by economic sociologists such as Michel Callon argue that most products do not come with inherent and unchanging qualities that make them instantly appealing to users. Instead, a product and its market become defined together through an entangled process in which stand-alone product features are defined (objectification) and adjusted to the client’s individual needs (singularisation). Throughout the process, the object is progressively transformed into a product that is bought and used. As the product begins to enter the buyer’s world, its relevant qualities that stabilise may be potentially disruptive to prior products (see the smartphone).

We use this theory to analyse technology development in professional services. What this theory suggests is that no matter how much established professionals aim to be ahead of the curve and develop cutting-edge big data tools, a novel technology that is not somehow attached to a buyer’s needs is not disruptive (see Google Glass). Our research method is to follow tech projects in different Big Four firms over extended periods, interviewing their technology teams and decision-makers.

We find that the process of professionals providing technology unfolds not only as a constant back-and-forth shaping of product qualities and buyer needs, but also as one of transforming the professional organisation. The increasing entanglement with products and markets has the potential to fundamentally disrupt the professional business model.

Prior expansions of the professional business model that involved technology were more similar to commodification, a process whereby accounting firms reworked new areas of expertise as a scalable assurance or advisory service. They articulated value propositions for hardware and software that had been developed elsewhere, by absorbing them into the traditional consulting model, selling thousands of billable hours of expert time — ERP implementations being just one example.

However, the new analytics tools that professionals are now developing release aspects of professional work from the involvement of the (human) professional. In the traditional model the human expert sells billable hours and establishes trust in the superiority of her expertise through personal client relationships. Digital solutions are clearly distinguishable objects that sell for a usage fee. At the same time, they are up against the culture of the professional firm, for which product qualification is an alien concept, despite how commercialised these firms have become.

Most importantly, consultants have turned out to be little equipped to sell technology. The ways of working with clients, in long-term engagements and offering a wealth of services, does not prepare professionals to enlist a market in articulating the properties of a stand-alone device.

Figure 1. How technology investments change the professional business model

Disrupting the disruptors

Our story could end here with the prediction from a recent Financial Times article, citing organisation scholars Henderson and Clark’s classic study that established firms fail to innovate because they cannot replicate the agility that is necessary to innovate successfully. However, this is not what we see in the established professional firms. As they try to create and sell their technologies, they are gradually making changes in their organisations. While most of the publicly visible activity focuses on building digital skills, such as coding or data analysis, a parallel and equally significant change is taking place somewhat unnoticed. Chiefly, professional firms have had to create new roles and hire staff with new competencies in sales and marketing, who bring expertise to consultants on how to devise propositions specifically for technology, and guide product development teams in relating the capabilities of their technology applications to potential audiences.

However, having sales-type roles in a partnership structure raises new questions in itself, such as those of compensation and career. Salespeople are usually paid in commission after deals instead of billable hours, and they do not fit the progression in the partnership structure if they do not ‘own’ client relationships. There is also a question of who owns and who is accountable for the technology products and budgets. We have seen the formation of in-house developer teams who work on their projects in addition to their consulting tasks, but equally, the launch of partnerships with proven technology firms. Finally, the very fabric of client relationships, which are core to professional services, is changing as consultants start using their analytics tools with and for clients. Consequently, trying to embed technology products more deeply in professional firms involves a change of culture, from consultants only proposing projects that are most likely to generate revenue (‘gatherers’), to accepting uncertainty and potential failure (‘hunters’).

Transforming expertise from Big Four into Bit Four

Our research shows that creating demand for professional technology objects requires new competencies from professionals that have to do with markets. The professional firms we observed were gradually changing some of their defining structures to accommodate the needs of product qualification: the thinking about what a technology can do and who it can appeal to, in constant motion.

Our study calls attention to the market and marketing aspect of professional expertise. Besides the governance dilemmas surrounding the Big Four, such as auditor independence, we must now turn our attention to the market-building expertise, the sales and marketing affinities of audit firms. In fact, we cannot rule out that being in the business of technological disruption will involve the transformation of assurance and advisory businesses into sales-driven organisations.

Finally, the move into technology is deepening the divide between the Big Four firms and the rest of the accounting profession. Deep pockets separate those who can invest in advanced digital solutions, sales, and marketing from those who cannot and must be technology and client ‘takers’, in danger of being automated away and pushed out of market conversations. This new digital divide is a significant problem in a system of professions pledged to serve the public interest.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post appeared originally on R&R, the magazine of LSE’s Centre for Analysis of Risk and Regulation (CARR), with the title “From gatherers to hunters: technology-led disruption of the professional business model”.

- This piece is NOT under a Creative Commons licence. © R&R Magazine. All rights reserved.

- The post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by D1_TheOne, under a Pixabay licence

- When you leave a comment, you’re agreeing to our Comment Policy.

Yasmine Chahed is lecturer in accounting at LSE

and a research associate at LSE’s CARR (Centre for Analysis of Risk and Regulation). Trained in economics, law, and business administration, she has a unique 15-year background in researching the links between regulation, corporate reporting, and corporate governance. She frequently works with board members and senior executives for her investigations into the annual report production process, digital transformations in accounting and professional firms, and the evolution of narrative reporting. Yasmine holds a PhD in accounting and finance and an MSC in law and accounting from LSE, and joined the department of accounting as full-time faculty in 2008. She is a member of the Financial Reporting Council’s Financial Reporting Lab Steering Committee, and a Fellow of the Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce . Prior to her academic career, Yasmine worked in the audit and assurance and corporate finance practices of two global professional services firms. As a member of the Advisory Group for the FRC’s major project on the Future of Corporate Reporting, Yasmine continues her mission to demystify theory and inform better questions in practice.

Yasmine Chahed is lecturer in accounting at LSE

and a research associate at LSE’s CARR (Centre for Analysis of Risk and Regulation). Trained in economics, law, and business administration, she has a unique 15-year background in researching the links between regulation, corporate reporting, and corporate governance. She frequently works with board members and senior executives for her investigations into the annual report production process, digital transformations in accounting and professional firms, and the evolution of narrative reporting. Yasmine holds a PhD in accounting and finance and an MSC in law and accounting from LSE, and joined the department of accounting as full-time faculty in 2008. She is a member of the Financial Reporting Council’s Financial Reporting Lab Steering Committee, and a Fellow of the Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce . Prior to her academic career, Yasmine worked in the audit and assurance and corporate finance practices of two global professional services firms. As a member of the Advisory Group for the FRC’s major project on the Future of Corporate Reporting, Yasmine continues her mission to demystify theory and inform better questions in practice.

Zsuzsanna Vargha is associate professor in the management control department at ESCP Europe Business School in Paris, and an LSE CARR research associate. Prior to joining ESCP, she was associate professor at the University of Leicester Business School and LSE fellow in accounting. Zsuzsanna holds a PhD in sociology from Columbia University and an MSc in economics from Budapest Corvinus University in Hungary. Her research is interdisciplinary, bringing together approaches in accounting and finance with organisation studies and economic sociology. Her interests have centred on questions of performance and valuation at the boundaries of organisations and markets, specialising in financial services and the digital economy. Currently Zsuzsanna is visiting fellow at the Max Planck Sciences Po Center on Coping with Instability in Market Societies. She studies the impact of technologies on client relationships in different settings, such as data-driven personalisation in consumer markets and digital disruption in professional services.

Zsuzsanna Vargha is associate professor in the management control department at ESCP Europe Business School in Paris, and an LSE CARR research associate. Prior to joining ESCP, she was associate professor at the University of Leicester Business School and LSE fellow in accounting. Zsuzsanna holds a PhD in sociology from Columbia University and an MSc in economics from Budapest Corvinus University in Hungary. Her research is interdisciplinary, bringing together approaches in accounting and finance with organisation studies and economic sociology. Her interests have centred on questions of performance and valuation at the boundaries of organisations and markets, specialising in financial services and the digital economy. Currently Zsuzsanna is visiting fellow at the Max Planck Sciences Po Center on Coping with Instability in Market Societies. She studies the impact of technologies on client relationships in different settings, such as data-driven personalisation in consumer markets and digital disruption in professional services.