In much of the developing world, economic power is largely concentrated in the hands of a “market-dominant” ethnic minority. The classic case is southeast Asia, where the Chinese, usually a tiny proportion of the population, enjoy an overwhelmingly dominant economic position. In Malaysia, the average Chinese household had 1.9 times as much wealth as the Bumiputera (Khalid 2007); in the Philippines, the Chinese account for 1 per cent of the population and well over half the wealth (Chua 2003). The same is true in varying degrees in Indonesia, Burma, Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam. Southeast Asia is an acute but by no means isolated example, from Jewish oligarchs in post- Soviet Russia, who are six of the seven richest men in the country; to Indians in east Africa; to the Lebanese in Sierra Leone and the Ibos in Nigeria, the picture that emerges is that certain groups of ethnic minorities often do disproportionately well in economic terms (see Chua 2003). Naturally, disparity between the economic power of an ethnic minority and the disadvantaged position of the majority ethnic group is a potential source of political instability. However, market-dominant minorities have received surprisingly little attention from economists.

In a recent paper, we provide a valuable piece to the literature by taking Malaysia as an example and analysing the evolution of income inequality among different ethnic groups. Most importantly, as the racial issue has long been a fixture in Malaysian politics, by studying the impact of Malaysia’s long-standing affirmative action policies on income distribution, we hope to provide insights on economic policy design for mitigating ethnic tensions and improving social cohesion in Malaysia and other countries facing the same issue.

From the 1970s to 1997, the growth rate of the per adult real national income in Malaysia has been 2.93 per cent. After a short setback following the Asian financial crisis, the economy has been catching up with an even stronger trend, and from 2002 to 2016, the growth rate of the per-adult national income was 3.7 per cent. However, the benefits of growth always remain a contentious issue, especially in a plural society such as Malaysia, with its multiracial, multireligious and multi-ethnic population.The largest ethnic group in the country is Bumiputera, a Malaysian term describing Malays and other indigenous peoples of Southeast Asia — it literally translates as son of the soil. In 2016, the population consists of approximately 68 per cent Bumiputera, 24 per cent Chinese, 7 per cent Indian, and 1 per cent others.

Inherited as a legacy of British colonial policies, the Bumiputera have remained the poorest group with the lowest average income, compared to the relatively richer minority contingent of ethnic Chinese and Indians, since Malaysia gained independence from in 1957. This economic imbalance, especially along racial lines, was a recipe for disaster. It naturally led to political and social instability, and racial riots erupted slightly more than a decade after the country gained its independence. As a response to the race riot in 1969, the government developed a comprehensive affirmative action plan known as the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1971.

The NEP was formulated with the overriding objective of attaining national unity and fostering nation-building through the two-pronged strategy of eradicating poverty and restructuring society. Especially, while the first prong is class-based, the second prong was designed to elevate the socioeconomic conditions of the Malays. The strategy was not new; in fact, the NEP expanded the affirmative action as enshrined in the Constitution. Article 153 of the Constitution specifically highlighted the special position of the Malays and this inclusive growth policy continued to be adopted throughout Malaysia’s post-NEP economic history and was included in the National Development Policy (NDP) (1990-2000) and National Vision Policy (2000-2010). The inclusiveness agenda continues in the New Economic Model (2010-2020), where the policy goal is for Malaysia to become a high-income country by 2020 as well as sustainable and inclusive; the latter is defined as “enabling all communities to fully benefit from the wealth of the country” (National Economic Advisory Council, 2010).

The evaluation of NEP and its successors is inconclusive. On one side, to some extent, it achieved remarkable results by reducing poverty from nearly 50 per cent in 1970 to less than 1 per cent in 2014. The income gap also shrank. Household income inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, narrowed from 0.513 in 1970 to 0.446 in 1989 to 0.410 in 2014. On the other side, schemes favouring Malays were once deemed essential to improve the lot of Malaysia’s least wealthy racial group; these days they are widely thought to help mostly the well-off within that group, while failing the poor and aggravating ethnic tensions. Interestingly, the introduction of the NEP was a direct result of the racial clash triggered by severe losses of the ruling government in the 1969 general election, where they lost more than half of the majority votes. In a recent election (2018), as a dramatic twist, the coalition that ruled Malaysia uninterruptedly since its independence lost to an opposition coalition. The root cause was not unlike the cause of political changes in the past — the Malays felt that the benefits from growth did not trickle down to them, and only the well-connected groups (read: cronies) who were involved in corruption enjoyed the fruits of development. The recent election also showed that the majority of Chinese voted for the opposition, as occurred in 1969.

By combining information obtained from national accounts, survey data, and fiscal data, this paper attempts to construct the first Distributional National Account (DINA) for Malaysia and systemically address the fundamental question mentioned above: In terms of income growth, which income class and ethnic group benefits from economic growth and to what extent, especially considering that Malaysia has an extensive race-based affirmative action policy? To obtain a full picture of the evolution of inequality in Malaysia, ideally, we would carry out the analysis for the period 1957-2016, but due to data limitations, we focus on the period 2002-2014, after the Asian financial crisis (AFC). In other words, we provide only partial answers to the question posed earlier: Who benefited from post-AFC economic growth?

A. Evolution of income inequality

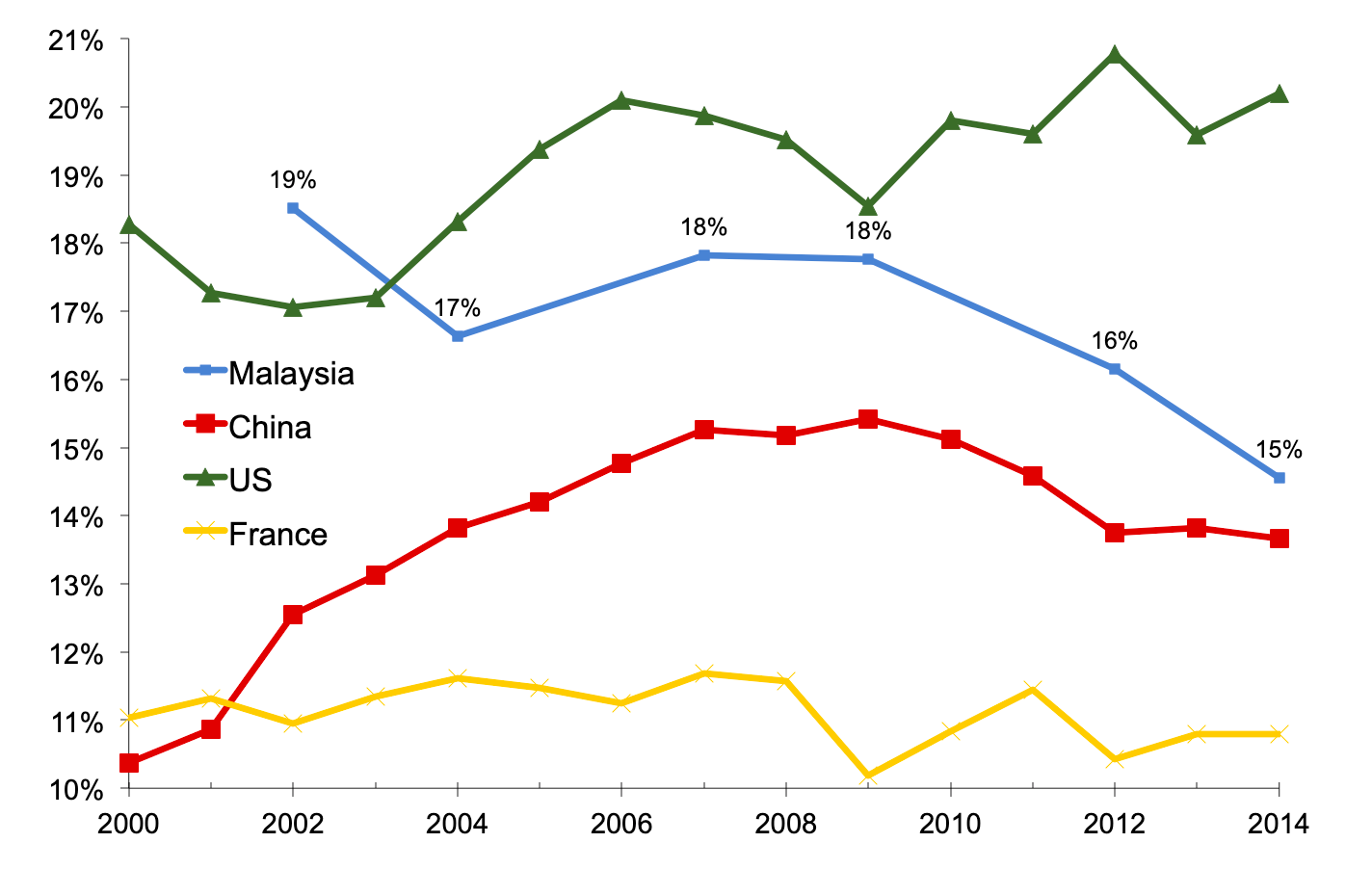

Figure 1. Income shares: top 1 per cent Malaysia vs. top 1 per cent in other countries (pre-tax national income)

Notes: Distribution of pretax national income (before all taxes and transfers, except pensions and unemployment insurance) among adults. Equal-split-adults series (income of married couples divided by two).). Imputed rent is included in pre-tax fiscal income and pre-tax national income series.

Figure 2. Income shares: top 10 per cent Malaysia vs. top 10 per cent other countries (pre-tax national income)

Notes: Distribution of pretax national income (before all taxes and transfers, except pensions and unemployment insurance) among adults. Equal-split-adults series (income of married couples divided by two).). Imputed rent is included in pre-tax fiscal income and pre-tax national income series.

Figures 1 and Figure 2 compare our Malaysian DINA top income series with the DINA series recently computed for the US (Piketty, Saez and Zucman, 2018), France (Garbinti, Goupille and Piketty, 2018) and China (Piketty, Yang and Zucman, 2019). These series use the same methodology as the one applied in this paper: they all attempt to combine information obtained from national accounts, surveys, and fiscal data to estimate the distribution of pretax national income (including undistributed profits and other tax-exempt capital income) among equal-split adults.

In 2002, Malaysia’s inequality level was extremely high: its top 1 per cent income share was 19 per cent and the corresponding number for the top 10 per cent was 44 per cent, which is higher than those of the US and substantially higher than those of China. However, while we observe a trend of increasing inequality after 2002 in the US and China, Malaysia’s inequality has been decreasing. By 2014, we see that income inequality in Malaysia is much lower than it is in the US and similar to the level in China, but still significantly higher than the level in France.

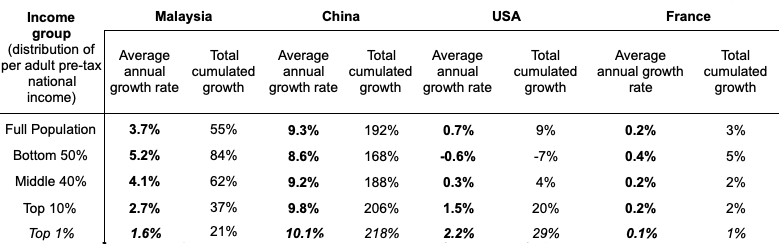

Table 1. Income growth and inequality 2002-2014: Malaysia vs. other countries

Sources: China: this paper. China: Piketty, Yang, Zucman (2019). USA: Piketty, Saez and Zucman (2018). France: Garbinti, Goupille-Lebret and Piketty (2018). Distribution of pre-tax national income among equal-split adults. The unit is the adult individual (20-year-old and over; income of married couples is split in two). Fractiles are defined relative to the total number of adult individuals in the population. Estimates are obtained by combining survey, fiscal, wealth and national accounts data.

Table 1 compares the distribution of 2002–2014 real income growth in Malaysia, the US, China and France. Aggregate growth has obviously been different in the four countries. As emerging economies, both Malaysia and China have experienced exceptional growth, especially China. The average per adult national income has increased by 55 per cent in Malaysia (corresponding to an average annual increase of 3.7 per cent) and almost tripled in China, while it has increased by 9 per cent in the US and 3 per cent in France for the same period.

Despite the significant economic upswing, Malaysia’s growth is featured by its strong inclusiveness. From 2002 to 2014, the growth rate accruing to the bottom 50 per cent has been significantly larger than the growth rate of the top 10 per cent (which is much larger than that accruing to the top 1 per cent). This is in stark contrast with the growth rate in China and the US. Especially, in the US, for the same period, total growth accruing to the bottom 50 per cent is -7 per cent compared to 29 per cent to the top 1 per cent. The result for France is similar to the result for Malaysia; e.g., the income per adult in the bottom 50 per cent is growing faster than that of the top (the top 1 per cent and the top 10 per cent). However, the average real income per adult growth rate is much lower in France than in Malaysia for the study period; e.g., the total cumulated growth is 0.2 per cent in France and 3.7 per cent in Malaysia.

B. Evolution of income inequality by ethnicity group

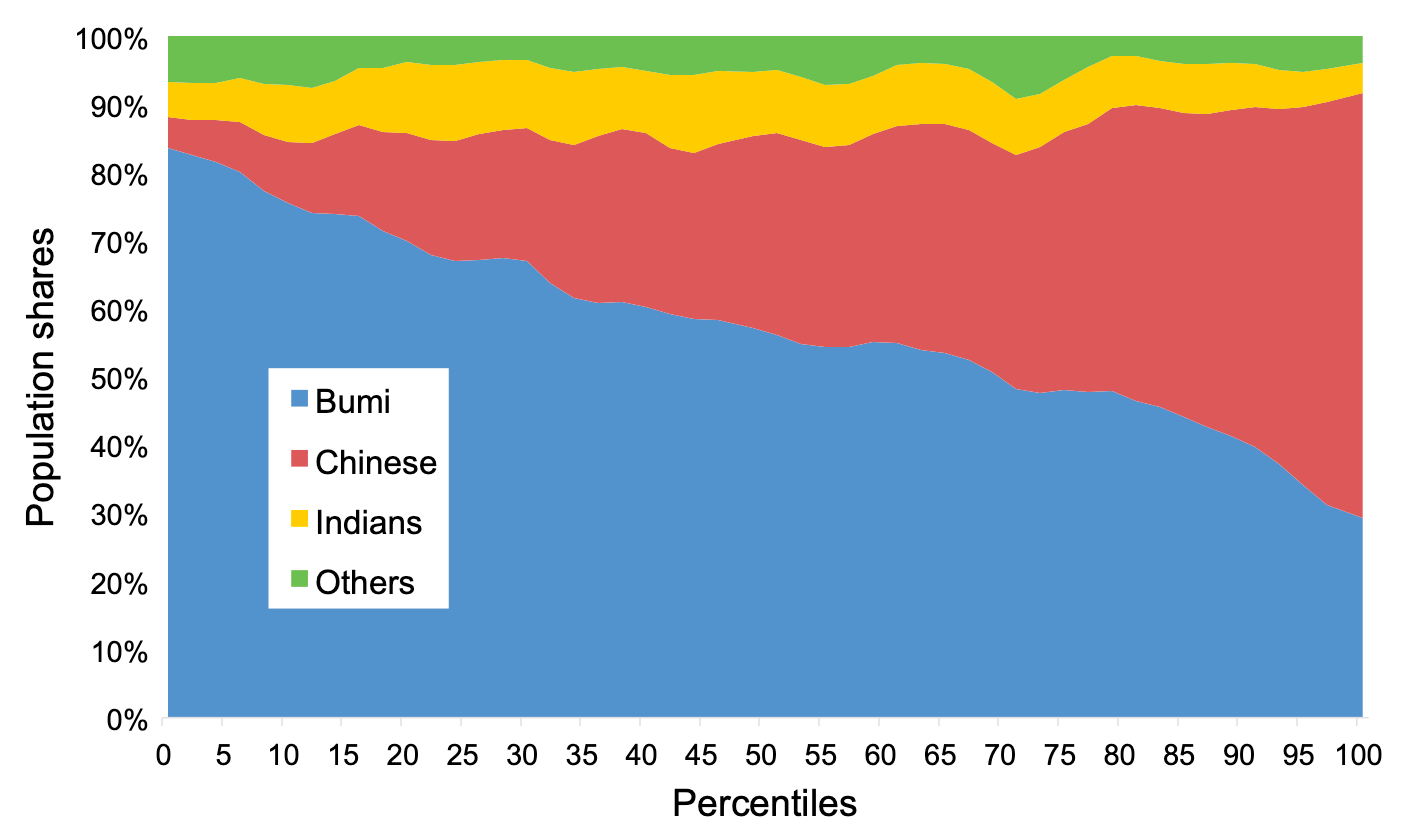

In this section, we begin by estimating the share of the population that are Bumiputera, Chinese and Indians for different income groups, especially for the top 1 per cent and the bottom 50 per cent Malaysian adults. This will allow us to respond to important questions regarding racial disparity in Malaysia.

Figure 3 illustrates the population share of Bumiputera, Chinese, Indians, and other ethnic groups by percentiles of real income per adult for 2002. It is quite striking to see how the share of the Chinese increases when approaching the top, contrasting with the sharp decrease in the share of the Bumiputera. Of the total Malaysian adults in 2002, 61 per cent are Bumiputera, 30 per cent are Chinese, and 8 per cent are Indians; however, in the top 1 per cent, Bumiputera account for only 24 per cent, Indians account for 3 per cent and the Chinese account for 72 per cent. Clearly compared to Bumiputera and Indians, Chinese are over-represented. This gap was mitigated in 2014; however, the contrasting pattern persists: among the richest one percent of Malays. (See Figure 4).

Figure 3. Population shares of ethnic groups in each percentile, 2002 (pre-tax national income)

Note: Population shares are calculated for each 2 percentiles using Kernel-weighted local polynomial smoothing method.

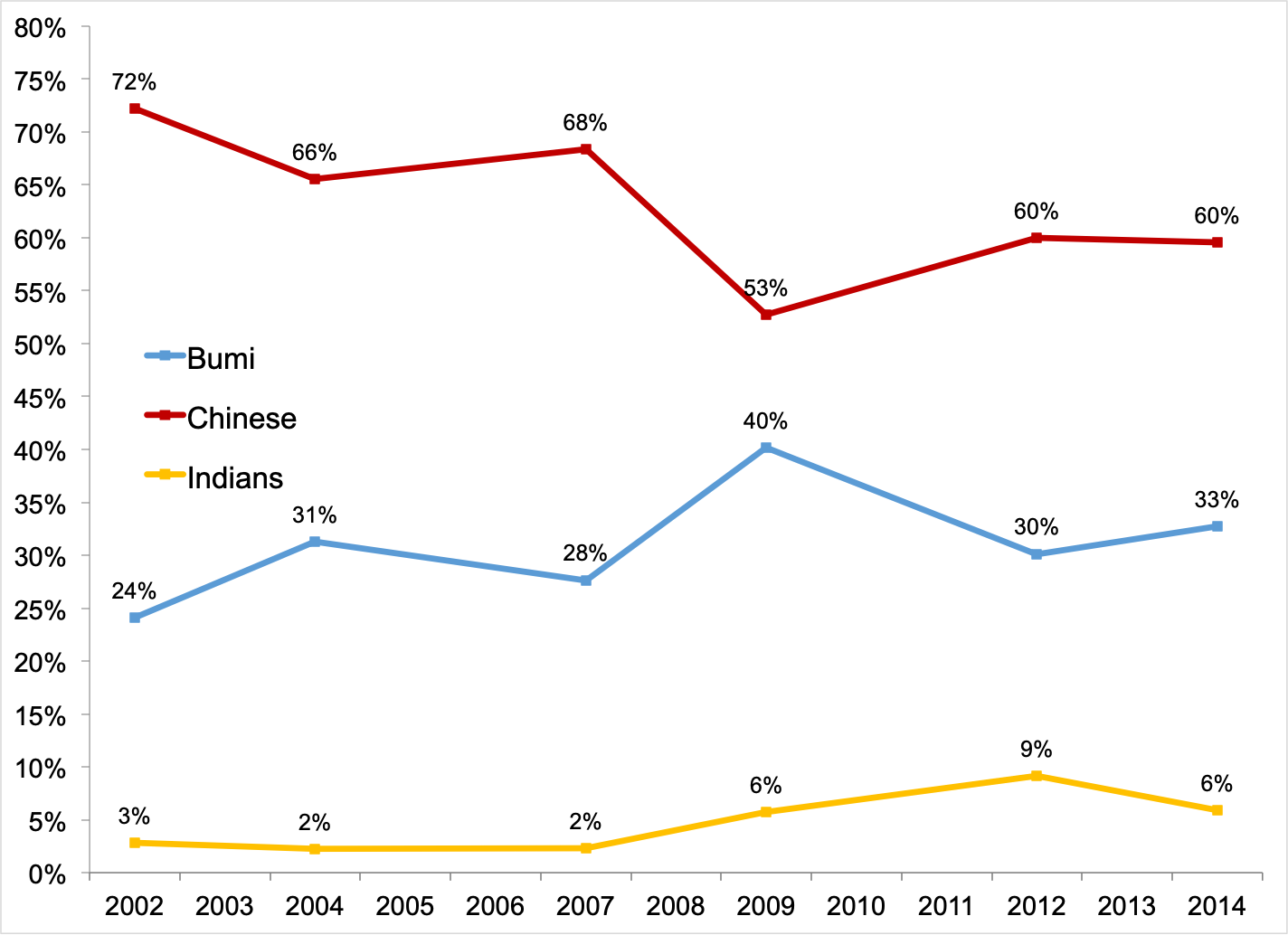

Figure 4. Population share by ethnic group – the top 1 per cent income group (pre-tax national income)

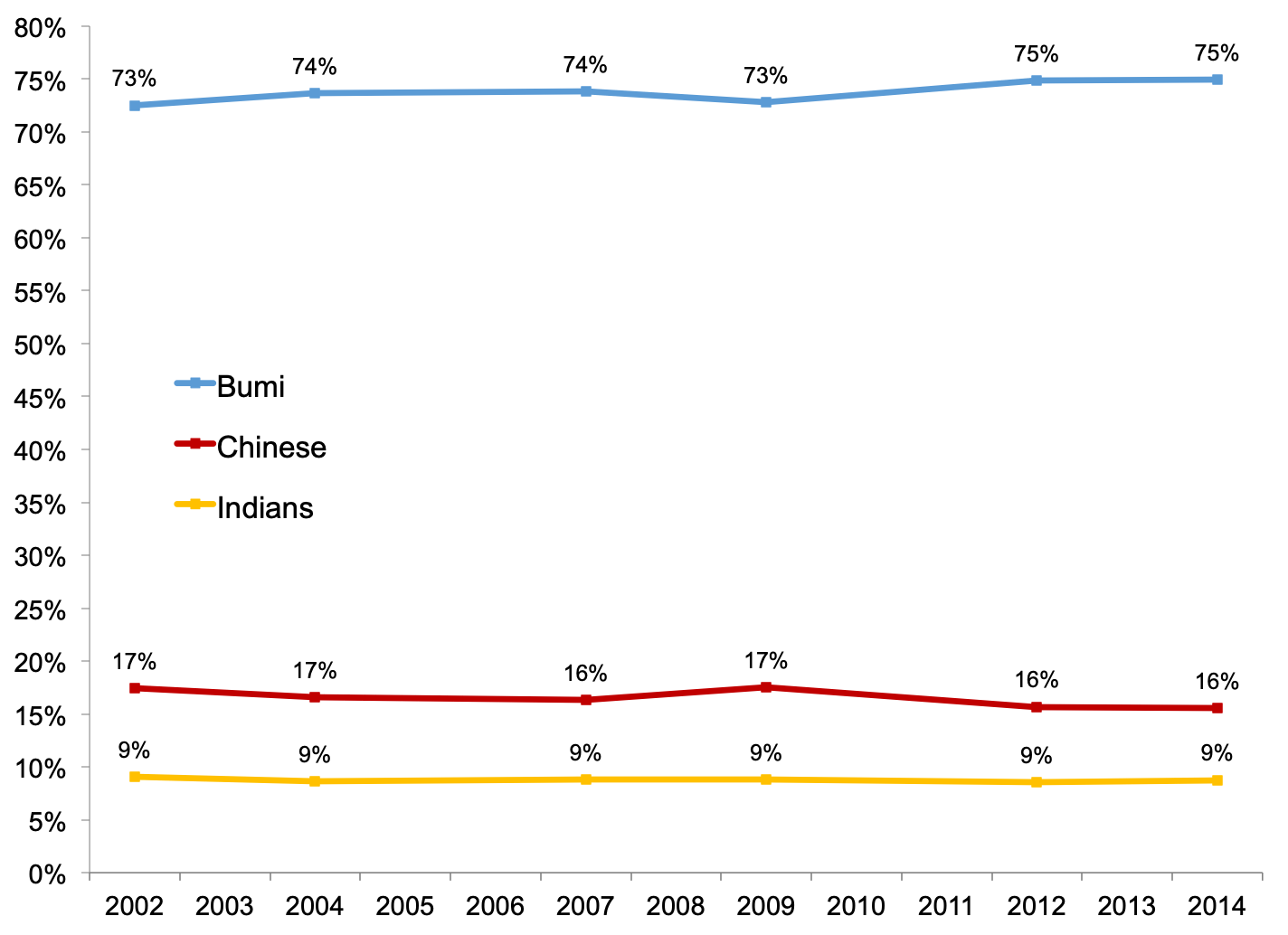

As important as it is to understand the unbalanced population distribution at the top, it is equally crucial to look into the poorest segment (e.g., the bottom 50 per cent Malaysian adults), especially when policymakers and the general public evaluate affirmative policies. As Figure 5 shows, in 2002, in the bottom 50 per cent of Malaysian adults, 73 per cent were Bumiputera, 17 per cent were Chinese, and 9 per cent were Indians. Until 2014, the trends of the three ethnic groups were very stable. Thus, when pro-Bumiputera policies improved the economic status of low income Bumiputera, approximately one-quarter of the population in the bottom 50 per cent was left behind. This segment of the population is made up of non-Bumiputera Malaysians, approximately 29 per cent of total Chinese and 56 per cent total Indians.

Figure 5. Population shares of ethnic groups in the bottom 50 per cent (pre-tax national income)

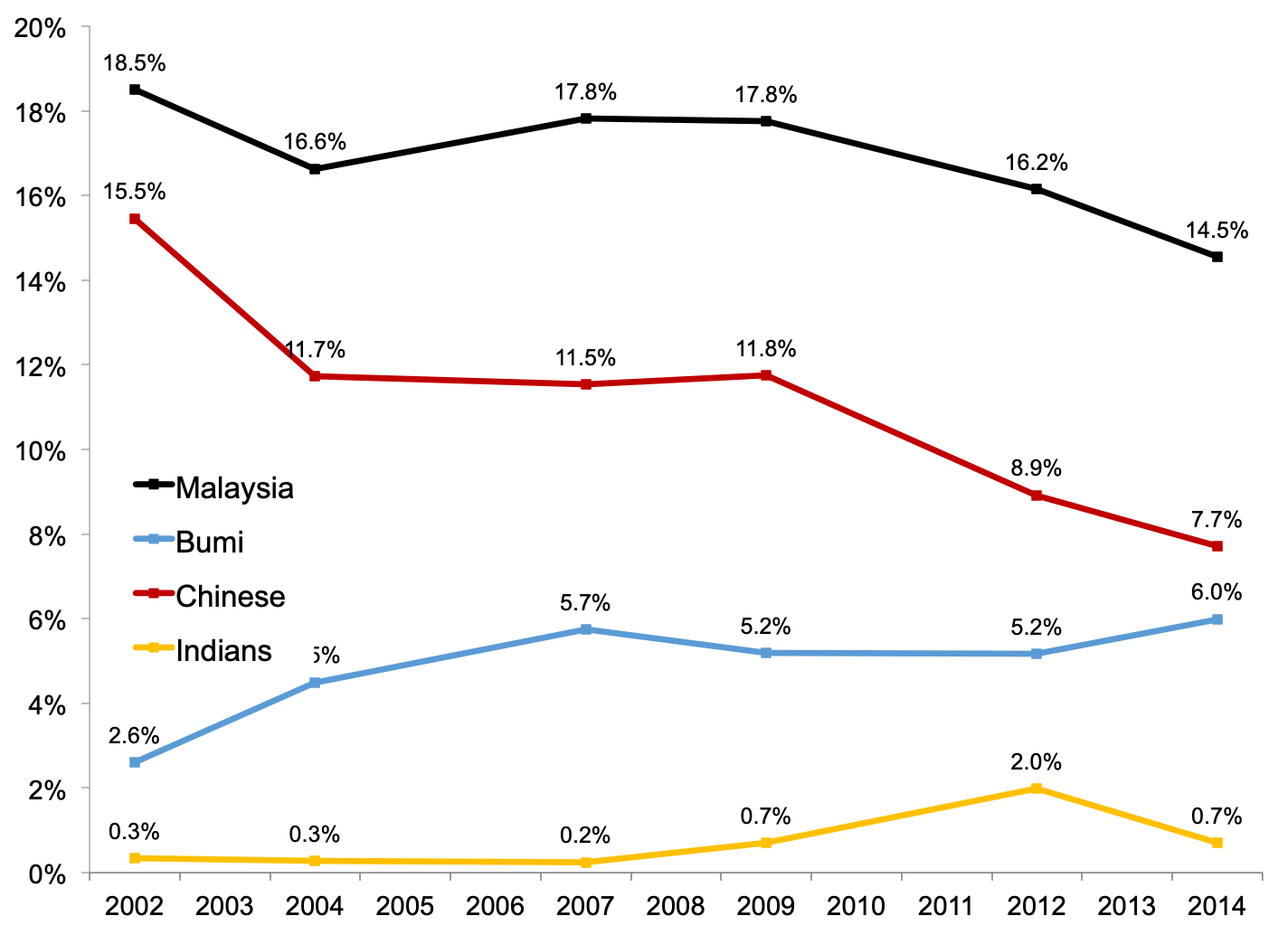

We now further analyse and decompose the income share (e.g., the top 1 per cent, the top 10 per cent, the middle 40 per cent and the bottom 50 per cent) by ethnic groups. As shown in Figure 6, the decline in the top 1 per cent share is dominated by two trends: a strong decrease in the share of Chinese and a significant increase in the share of Bumiputera. Among the top 1 per cent of Malaysian adults, the income share of the Chinese decreased by almost half, from 15 per cent in 2002 to 8 per cent in 2013. The share of the Bumiputera doubled in the same period, increasing from 3 per cent to 6 per cent. The share of the Indians also increased significantly and more than doubled from 0.3 per cent to 0.7 (however, in terms of the absolute level, the effect is minimal). The results for the top 10 per cent of Malaysian adults are similar to those for the top 1 per cent.

Figure 6. Decomposition of top 1 per cent income shares by ethnic group (pre-tax national income)

Figure 7. Decomposition of bottom 50 per cent income shares by ethnic group (pre-tax national income)

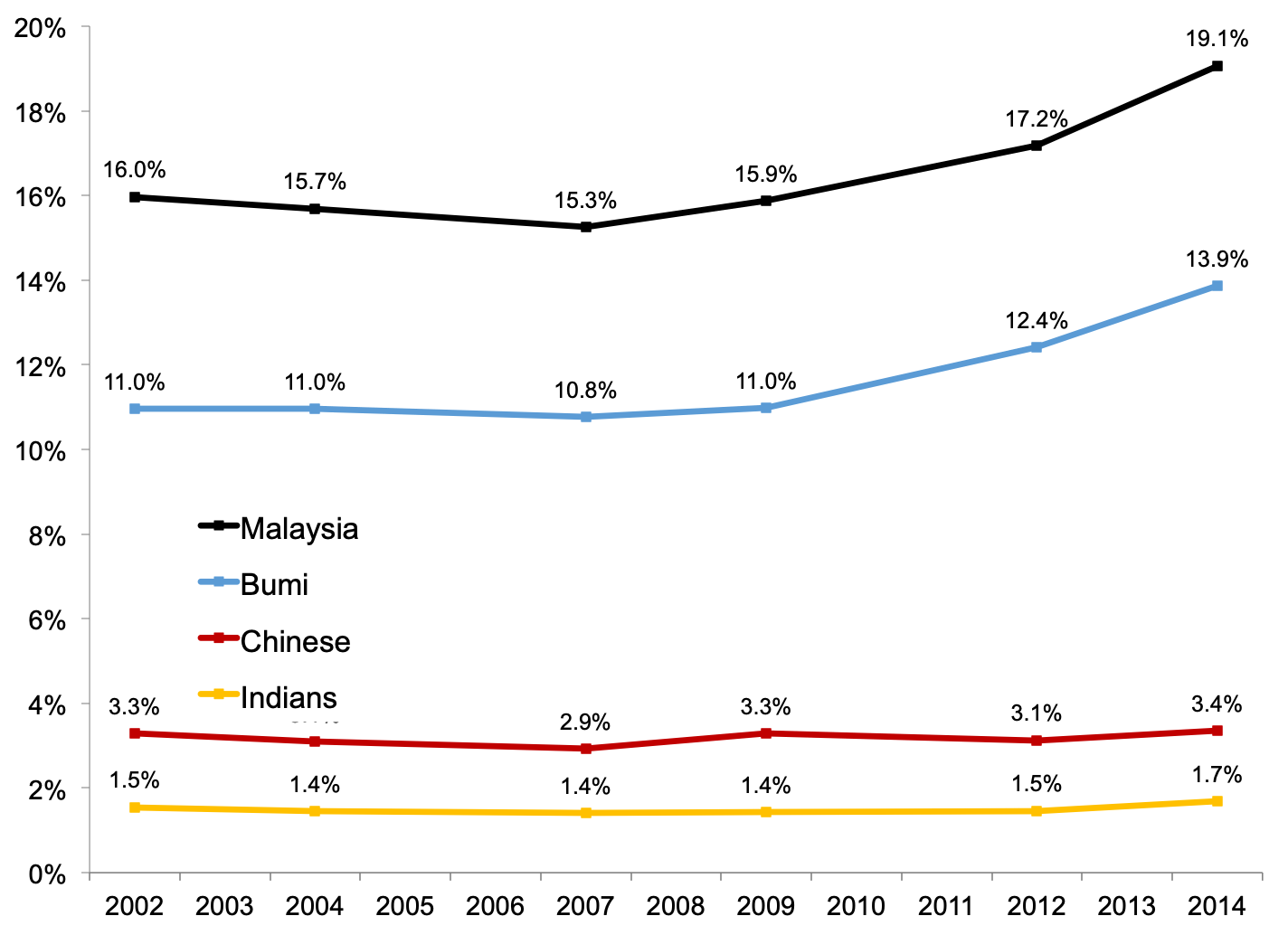

Using the same procedure, we decompose the bottom 50 per cent income shares. The results for the bottom 50 per cent are different from those of the top 1 per cent and top 10 per cent. The substantial expansion in the bottom 50 per cent income share was solely driven by the increase in the share of Bumiputera, e.g., from 11 per cent in 2002 to 14 per cent 2014, while the share of Chinese and Indians stagnated at 3 per cent and 2 per cent, respectively (see Figure 7). For the middle 40 per cent, the moderate increase of the income share can be decomposed to a steady increase in the share of Bumiputera (from 20 per cent in 2002 to 24 per cent in 2014) and a slight decrease in the share of Chinese (from 16 per cent in 2002 to 15 per cent in 2014).

In conclusion, the decrease in income inequality in Malaysia was mainly driven by two opposite trends: a sharp decrease in Chinese income shares in the top and a substantial increase in Bumiputera income shares in the top and bottom.

By further decomposing the pretax personal income share for both Chinese and Bumiputera in the top 1 per cent by income sources, (e.g., wage income, self-employed income, property income, and transfer income), we found, strikingly, the decrease in the share of the Chinese at the top is mainly driven by the decline of the Chinese property income share, from 9 per cent of total pretax personal income in 2002 to 3 per cent in 2014. Meanwhile, the increase in the share of the Bumiputera is driven almost equally by the increase in wage income, self-employed income and property income (the income shares for each type of income source increased by 1 per cent from 2002 to 2014). We conduct the same exercise with the share of the Bumiputera in the bottom 50, and the results show that approximately two-thirds of the increase in the Bumiputera share is driven by the increase in the Bumiputera wage income share.

Finally, to address the core question of this paper: In terms of income growth, which income class and ethnic group benefits from economic growth and to what extent, we decompose the average growth rate of real per adult national income in Malaysia by both income groups and ethnic groups (Figure 8). Although Malaysia’s growth for the period is featured by its strong inclusiveness, macro growth has obviously been different in the three ethnic groups. In particular, in the top 10 per cent, the average growth rate per adult national income for Bumiputera is 5.4 per cent, compared to 1.2 per cent for Chinese and 4.6 per cent for Indians. The gap in the growth rate among the different ethnic groups was large in the top 10 per cent; however, it is even larger for the top 1 per cent. In the top 1 per cent, the average growth rate for Bumiputera was 8.3 per cent, which is sharp contrast to -0.5 per cent for Chinese and 3.4 per cent for Indians.

Figure 8. Decomposition of growth rate of real income per adult, 2002 to 2014 (pre-tax national income)

Compared to the top income group, the difference in the average growth rate among the ethnic groups are not significant for the middle 40 per cent and bottom 50 per cent. For the middle 40 per cent, the average growth rate for all three ethnic groups was 4.1 per cent, and for the bottom 50 per cent, the Bumiputera’s growth rate of average per adult national income was 5.4 per cent, which was slightly higher than that of the Chinese at 4.9 per cent and Indians at 4.7 per cent.

The most important implication of Figure 8 is that although the middle 40 per cent and the bottom 50 per cent benefited significantly from economic growth, the Bumiputera in the top income groups (the top 1 per cent and the 10 per cent) benefited the most from economic growth. In sharp contrast, the income of the Chinese in the top income groups deteriorated. In a way, the strong growth in high-income Bumiputera occurred at the cost of a decrease in Chinese and the slow growth of Indians in the top income groups.

To conclude the findings of this paper, Malaysia’s growth for the period of 2002-2014 included significant and relatively egalitarian (among different ethnic groups) growth in the middle 40 per cent and bottom 50 per cent and a strong divergence among the Bumiputera, Chinese and Indians in the top 1 per cent and top 10 per cent. Thereby, Malaysia’s growth features both an inclusive redistribution between income classes as well as a combination of affirmative action policy and the free flow of capital(ism).

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the authors’ Income Inequality and Ethnic Cleavages in MalaysiaEvidence from Distributional National Accounts (1984-2014), World Inequality Database, working paper No. 2019/09

- The post gives the views of its authors, not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by Trey Ratcliff, under a CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0 licence

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy

Good article to read in past time. However it did not discuss the main point of economic disparity in Malaysia. It failed to deliver further analysis about how far, deep and powerful grip on Malaysian economy by ethnic Chinese since beginning of Malaysia Federation formation, as the main culprit of disparity of wealth among Malaysian people.

While there was huge problematic among corrupted Government ministers and officials during NEP implementation, the basic point is they failed to eradicate the powerful clan of Chinese businessmen that almost controlling all spheres of business opportunity available.

Anyway i do think not everyone is born in golden plate or born with business traits in their bloodline. Thus it is hard for the majority of them to conduct in business and thrive in it. That is why many Malays failed miserably in doing business while you can see almost everything failed with National GLC’s has been at fault of failed administration and lacks business direction of these Malays entrepreneurs. Proton, Malaysia Airlines, Felda, Perwaja, Feedlot is to name the few. These are the proof that Malays lacks business acumen in their bloodline. Altogether those failed GLC has been depleted hundred billions ringgit of Malaysian money and should be unforgiven.

I would like to further my argument (or suggestion if you rephrase it in a positive way) on how to eradicate poverty completely in Malaysia, regardless of race.

What is the main problem faced by communes everyday? The security of jobs,necessitous income & housing problem.

How to solve this problem in shorter time? There is a way and I will show how to do it.

Contradict to whatever wealthy Prime minister Mahadhir badmouth that malays are lazy, they were not. They just need clear direction and progressive plan to harvest their talent and will. Which is what government failed to deliver since the sudden unfortunate death of smartest Malays leader, arwah Tun Razak.

Same with predicament of destitte Indians and bumiputera Sabah Sarawak. They are not lazy. They were unfortunate because both central federation and local leaders busy to gain wealth for themselves and failed to elevated their own people economy, resulting in prolonged stagnation.

Malaysia has a huge deposit of fertile land all around the country. The most of it located in Sabah & Sarawak.

The idea of Felda was ingenious and revolutionized the way to combat poverty in fast and efficient way. These idea was borrowed from the late of Russian Prime Minister P.Stolypin. Which later was murdered by command of jewish financier. If Russia success in their land reform, Russia people getting rich, they could not be used as proletariat insurgency against Tsar Nicholas II. There will be no revolution if people are happy and content.

What happen in Felda scheme? It successfully provided poor settlers with lands to work giving them staple supply of income. At the same time provided their family with house to cover them. The best part of it they didn’t needed any worry of housing loan repayment as they built it themselves (together with the help of settler community).

Altogether they have job security, steady income and house in one go. This is what Tun Razak plans and it proven successfully elevating poverty among Malays. In less than 30 years, many Malays were content and together they built the fame empire of Felda, which is listed as the biggest land farm owner in the world.

Today Malaysia have ridden with food supply problem which affected money outgoing flow just to satisfy people’s appetite. At last review we spend almost RM$50 Billion on food imports alone. Per year. And the amount growing more frightening each year.

Why don’t we grow vegetables supply ourselves? Why don’t we harvest our own rice, corn & wheat? Why don’t we tend our own livestock? The answer is simple yet delicate. People wanted to be farmers but at the same time they don’t have lands to start by. This is where Government should interfere and help.

Indian proved to be good cattle breeder. Why don’t give them a scheme like Felda and give them land to livestock cattle. Or sheep & goats. If they got this chance i think many of them would like to venture into full farmer. Name this venture as TernakMas.

Malays are not lazy. In the history of Malays archipelago, there has not been a single day people starving to death. Not even during the occupation of westerner. Only when Japanese army invaded but that’s another story. My point is Malays is not accustomed to trading but they are likely to succeed in farming & fishing. It was in their blood. Agriculture is what Malays do best. It’s proven with Felda, Felcra.

Why don’t make another Felda scheme let say name in as LadangMas. Give them land for them to settle. Make sure they grew specific type of crops which is best for their land type. Grew vegetables. Grew food supply.

Same as other bumiputera in Sabah Sarawak. They tend to be more successful perhaps their soil is more fertile and land banks in vastly superior available. I really confident in less than 20 years they will be no more poverty in Sabah Sarawak if these plans carefully executed and majority of bumiputera take part.

Sabah and Sarawak have distinctly special soil to harvest coffee. While the coffee prices are highly in demand now why don’t give them advance opportunity into these venture? Fight oligopoly from Vietnam and Brazil.

In less than 20 years this settlement will flourished and fully mature. Imagine we are able to self sufficient supply our own food and needed no more eagerness to import anything. Instead we might have been able to be net exporter if these plans going well.

RM$50 Billions of food import per year eventually going back into nation coffers. Ain’t that a good supplement for our own economy?

To be fully successful is to stop giving this land to conglomerate as their do not care about the wellbeing of the people. They just wanted to fulfill insatiable lust of their shareholder. Avoid giving them taking part of any of these communal farming as they will destroy the essence of it.

Let the people manage their own farm. Let them grew up. Let them be diligent farmers. Let them behold our own food security. Let them guarded our own food provision. Stop spending vigorously on import products.

I believe they will prosper and eventually develop into small scale enterprises. The food they grew can be processed into F&B products

This is roughly just an idea from decent rakyat. I hope it can reach government attention and can be delivered in the near future.

Blaming Chinese economic prowess will bring futile impact to Malays. They will always control the economy as they have advanced knowledge, well deep structure, strong guilds and rooted connection. Malays should accept they need more time to learn and adapt to business strategium. It will take time.

What Malays should do now is to root back into their nature. The best is to give them chances to be farmers. That’s what in their bloodlines. For centuries they have been excellent farmers. If not why colonials traders willing to sail from afar just to get Malays spices?

Thank for publish my comments.

This is a rather excellent reply. I would love to connect occasionally with you and discuss the foundations of your analysis and suggested solutions.

You can reach my at this email: malayrose2020@protonmail.com

while I agree that the agricultural sector in Malaysia should be enhanced and farmers should receive more assistance, saying that certain races are genetically predisposed to doing a particular economic activity is racist

The article does not take into account the saving/spending habits of different ethnic groups. There is often the claim that Malays are overall poorer and the Chinese are richer, but this is false. The Chinese, first of all, do not have access to government assistance like the Malays for housing and property and education. They are virtually locked out of the education system and the housing market. So, of course they need to earn a higher income to achieve the same standard of living as the Malays overall. And of course, most Malays gloat at the poverty of the Chinese. The Malays also have a tendency to spend all their income while the Chinese save – and this is because they have to, or else end up in poverty.

I disagree. The claims about Malays/Bumis are poorer than Chinese is right. Eventhough the Malays/Bumis are privileged, it does not guarantee that it will help them in achieving stable income or higher than the Chinese. This is because the Chinese are majorly populated in the urban areas while Malays are concentrated in the rural areas. Therefore, the Chinese have higher chances to get better jobs, higher incomes and live a stable life. But all in all, I am not pointing fingers at any race. We go way back. This is all because we were colonized by the British. This is because the British separated the Malays from the Chinese and Indians. I strongly believe that if we were not separated this country would achieve prosperity and the people would not suffer from being poor no matter what race.

Majority malay population also live in urban area and in rural area bcz malay are the biggest group there not chineses over all malay are increasing there wealth then Chinese bcz of government facilities

As a Chinese Malaysian, I wouldn’t say the Malays are lazy. Some of them work for really long hours every day. However, I would say that the Malays and the Chinese have somewhat different values and life outlook. The Malays are very religious, and are generally contented with a stable sustainable way of life. On the other hand, the Chinese are very ambitious, willing to take great risks to become millionaires and even billionaires. It is this drive that has pushed many Chinese to financial heights.

In my opinion, some form of affirmative action was justifiable at the time of independence about 60 years ago, when 60% bumiputeras occupied just a few percents of the national wealth, as such policies would effectively channel financial assistance to the hardcore poor. However, the economic landscape has largely changed. Any further biased economic intervention may run against modern economic principles, deleterious to the national economy in the long run. There are many Chinese and Indians who are poor too. If we were to help, we should help whoever are poor regardless of race. Dividing the country unnecessarily along racial lines will only weaken social cohesion and harm national unity.

Contrary to popular beliefs, some of the richest people in Malaysia are Malays. Because of political complications, they have generally avoided making their wealth well known. I am sure they don’t need any living assistance from the society!

I’m sorry but I completely disagree with your argument. Unfortunately, spoken like a true Chinese Malaysian. In case you’re forgetting, bumiputera does not only cover Malays. They also cover bumiputeras in sabah and sarawak. Bumiputeras in S&S are not religious at all, as a matter of fact I’d argue that they’re even less religious than most people in Malaysia. They are also known to save money well too and prioritize education. At the end of the day, majority of big businesses in Malaysia are managed by the Chinese. This goes WAY back to colonial times. You should read up about how they dominate the major towns in sarawak and even until today. As the article said, it caused racial tensions and are still felt today. The reality is that, yes, Malays do have priority when it comes to receiving government contracts but you need to understand how this works. Many bumiputeras don’t come from affluent families and when they receive contracts, they are unable to afford a lot of equipment and such. This is where the problem of subcontractors come from. Many of whom are Chinese. Contracts aside, the one characteristic the Chinese have thats very admirable is how they help one another. Sense of community is strong. It is way easier to conduct business with Chinese, if you are one. This is a FACT. It’s difficult to quantify, but it is based on empirical observations. Government bodies may hire more Malays, that is true and unfortunate, but a lot of private companies run by Chinese or with Chinese upper management, tend to be more biased towards their own. Social media is filled with complaints on this. There was even a video of an Indian man who wanted to commit suicid3 because of it. Ultimately, as someone who is mixed, I do think there should be more racial harmony. Of course. But let’s not lie to ourselves that the effects of colonialism don’t affect us today. There was a time when my bumiputera grandparents/parents would be the only non Chinese in school. It’s similar in the US. The whites had a head start to develop generational wealth (like the Chinese in Malaysia) and that’s why the rise of a wealthier class of African Americans and Hispanics is only slowly emerging today. African Americans have the highest poverty rate because they were unable to develop generational wealth earlier as compared to whites for obvious reasons (slavery, racially discriminatory policies). I’m unsure where you obtained your statistics about Malays being some of the “richest people” in Malaysia. I do agree there are many rich Malays, but as the report pointed out, on average, bumiputeras are poorer. If you’d accept anecdotal evidence, I can safely say I personally know more Chinese who evade tax and keep their wealth hush hush as compared to bumiputeras. You’re worried about social cohesion and so am I, but in the words of Syed Saddiq “it is important for me to ensure that especially those who are underprivileged, coming from poor family backgrounds deserve to be helped and assisted, which unfortunately today are majority Malay”. Pretending there’s no problem won’t make it go away.

I didn’t say all Bumiputeras are religious.

You seemed to miss my whole point. Let me emphasize it again here: there is no need to make a racial distinction when it comes to financial aid. True, on average Bumiputeras are poorer, but many of them are incredibly rich too. Then there are Chinese who are also very poor. Malaysia is like a bad doctor now, treating with medicine people who are not ill, while ignoring some who are sick simply because they can be grouped with people who are healthy. That’s what disgusted many non-bumiputeras, causing them to permanently leave the country they once loved. Some of the more progressive bumiputeras would also regard continued affirmative actions as a form of humiliation to their race. With Malays being the majority race in Malaysia, I don’t see any reason why they can’t get the so-called human support that they need. To institutionalize racial preferences is to build a solid wall separating the different races, preventing the races to unite. It is divisive inherently.

As Martin Luther used to say, people should be judged by the content of their character, not by the colour of their skin. So what if the person is a Malay or Chinese or Indian or Kadazan or American or African? For the sake of everyone, as long as the person is capable and righteous, let the person lead and manage. As long as political and business leaders are chosen because of their race and not because of their ability and fair-mindedness, as long as Malaysia remains locked by the shackles of racism, as long as unimportant racial preferences are institutionalized, the country can never realize her full potential.

I did support my claim with many facts that some of the richest persons in Malaysia are Malays. I won’t go into the details of individual criminal cases, and it is unwise to stereotype criminal tendencies with a race as a whole. Because of the sensitivity of the issue, I won’t list the facts here another time, lest my comment be moderated again. Lets just say the richest Malaysian is in fact not Robert Kuok, nor a member of a royal family.

I honestly don’t think the bumiputra policy helps the Malay. If only it make the thing worse. When I graduated, it was so hard to get a job because literally half of all job ads have a “must be able to speak Chinese” requirement. I finally get a job as an Insurance Adjuster making RM 1800 meanwhile my Chinese colleague was making RM 2300, eventhough we started only a couple of months apart. I later found out that these type of practices are common in small companies. I graduated with tons of student loan debt and I make minimum wage salary. It was hell for at least 5 years for me. So whenever people say the Malays have things easy, I wonder which part of my life is easy? Also to say Malay businessman benefitted from government contract and all is looking at the glass half full. Businesses who focuses on government contracts will not go beyond the local market. They become complacent and they don’t push themselves to go global. I honestly think Affirmative Actions doesn’t help anybody. In fact the policy make it worse for every single race.

Btw, I tend to disagree when u said the Malays are very religious. The word religious is subjective. Chinese people are not religious at all, compared to them you can say the Malays are very religious. Compared to several countries in the middle east I dont think we are “very” religious. I also know where you are going when u mentioned religion and my guess is I think you are trying to indicate that religion is the cause of lack of wealth in the Malay community. Well it is wrong because in Islam itself doing business is encouraged and is the most noble job out of any profession. The lack of wealth is not due to Islam or religion. It is due to race. In all of South East Asia all of their economy are dominated hy the Chinese. In the Philippines, a largely Christian dominated country, despite the Chinese being only 1% of the population they control half of the economy. There was a time when the US had to ban all Chinese from migrating to the US because the Chinese were starting to dominate every single industry in the US (Chinese exclusion act). The problem is not religion, it is race. The truth is nobody can compete with the Chinese if they live in the same country. People don’t want to live in a robot culture.

I disagree with the generalisation as a whole. Saying Chinese dominates the economy or that we are rich is as bad as saying Malays are lazy or that they have a better life.

To quote you, you are looking at the glass half full

I am from a single parent family and we had to take 100k+ debt as my mum was unemployed and my sib n i were still studying. We had to use her savings too to get by.

Still am, even now after we are working.

How am I rich ?

How is my family considered dominating the economy?

My mum was shopping for discounts, and a Malay lady next to her could actually scoff and remark “pura-pura” .

And if Chinese were so great, China wouldn’t be facing a looming unemployment crisis right now.

I really hate all these generalisation we keep on repeating. It groups everyone into neat little boxes, ignoring that people can have different lives outside of it even among the same race. It ignores the fact that poverty is not segregated by races and is frequently used as a fearmongering tool to deny them aid.

Inequalities happens in every country and in every system of government. In Malaysia, the stratification is more pronounced by race due to the skewed affirmative action applied by the government and pushed for by major political parties. Of late, the stratification seemed to be more pronounced in terms of religion, due to increased religiosity in recent times. It is a very entrenched divide, by means of race and religious fragmentation such that even with economic integration among the races, the chasm remains and this had become a real challenge, though not insurmountable. The Malays are generally poorer in numbers, primarily due to their large representation in the population, ineptitude in language of trade and work ethics and lack of ambition, however, there are equally many poor Chinese and Indians citizens in the country that fell through the cracks. If the country wants a reversal to progress, a multiracial and multi-religious country like Malaysia has a lot of potential as indeed there is strength in diversity, whether in the corporate world as well as in the society as a whole. To achieve true integration it first has to tackle the pronounced race & religious fragmentation to embrace multiculturalism in society, like what Singapore has done successfully. This would require more efforts in programs of integration and with the government curbing the spread of extreme religious ideologies. Affirmative action can still be implemented but it has to be targeted, and premised on need basis and not on entitlement by race. Such affirmative action programs has to be focused and transparent and monitored against set targets. The bigger challenge though, is institutionalized corruption which must be put in check. It also need to re-establish the independence of the three pillars of government, i.e. the Legislature, the Judiciary and the Executive, and this requires a massive structural overhaul which for the time being there is no political will to make it happen. At the same time, the country has to slowly introduce meritocracy in all spheres including the government sector, without which the beneficiaries of affirmative action has no reason to excel nor improve themselves. This change is required bearing in mind it is not sustainable for the assistance by the government in perpetuity without increasing productivity, and further compounded by the rent-seeking maneuvers of the powerful Malays over the other races for their self-enrichment, in the wake of a globalized economy with borderless competition.

From a human being point of view, implement limitation on others people growth in order to gain personal growth is bad ethic. The bumiputera policy is not a meritocracy system, as per the title of the of policy, people with bumiputera status will have more freedom in the country to do business( for example permit to own petrol station, permit to receive AP for vehicle import, permit to own shipping business etc.).and it is very tough for non-bumiputera to find job Malaysia due to the requirement of 100% bumiputera owned business policy. The question come as we are all human being, are you prefer to be bumiputera or non-bumiputera? You are Malaysia but you will never ever be recognized as one.

Alliance didn’t lose more than half of majority votes in the 1969 election, they only lost 2/3 majority. The loss in votes was contributed by more Malays voting for PAS than the Chinese voting for DAP. Alliance could still form government.