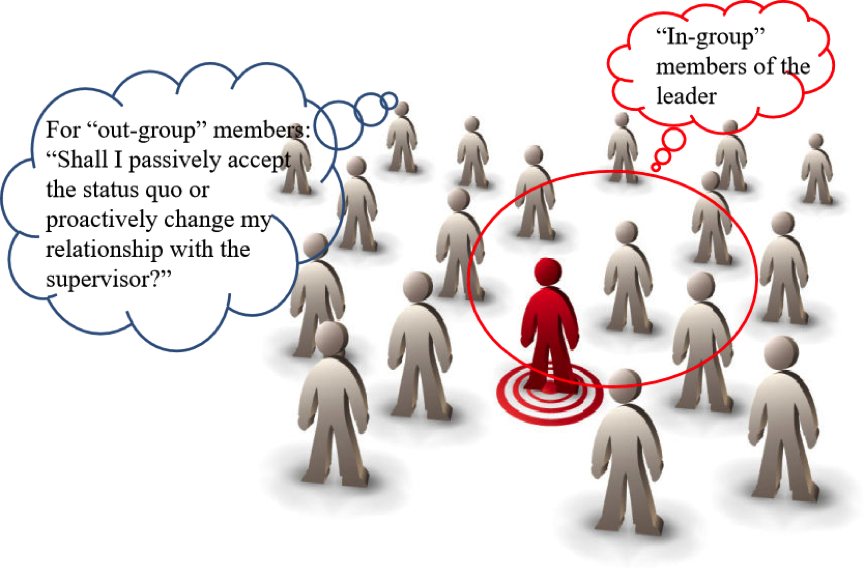

Imagine a prevalent phenomenon in the workplace: A leader has several direct reports, but only one or some of them are included in his or her inner circle to enjoy more opportunities for learning and growth. You may wonder: What chemistry has this group of followers generated in the daily interaction with the leader so that they are “chosen” as “in-group” members? For those who are outside of the leader’s inner circle, can they proactively change their situations or should they just passively accept the status quo?

We contend that followers’ proactive engagement in contributing valuable resources is critical to the quality of their relationship with bosses. Our research confirms this idea by demonstrating the proactive role followers’ taking charge can play in the resource exchange and relationship building process.

Figure 1. In- and out-groups around the boss

In academia, the term leader-member exchange (LMX) is used to describe the resource-based exchange relationship in a leader-follower dyad. The most crucial reason for leaders to have differential relationships with their followers is to achieve work efficiency and effectiveness. Although prior research has focused on leader behaviours as the dominant driver of LMX development, we contend that LMX development can be more fully understood by examining follower behaviour. Indeed, the increasingly uncertain work environments coupled with the added challenge of limited resources in today’s business world encourage leaders to rely more on their followers’ proactive behaviours and contributed resources to meet workplace challenges. Therefore, “whether this follower can proactively contribute resources to benefit my work” has become a key criterion in deciding whether the focal follower would be “invited” by their leaders to join the “in-group” circle.

Taking charge, referring to followers’ implementation of functional changes in their work, team, and organisations, is one of the most important proactive behaviours followers can engage in to develop better relationships with their leaders. It reflects the essence of proactive behaviours (i.e., self-initiation, change-orientation, and future-focus), and represents a general, as opposed to context-specific form of proactivity, making it more applicable to many situations in the workplace. For example, a front desk clerk can eliminate ineffective procedures for customers when observing long waiting queues. A salesperson may proactively implement new solutions to attract customers to boost the work unit’s revenues while dealing with a new competitor. An accountant may proactively design a new reporting system that can record previous transactions and prioritise any unsolved issues with all vendors, so that the organisation’s communications with vendors become clearer.

We reason that those who take charge can become leaders’ “trusted assistants” because they deliver valuable service resources that make their leaders’ work more effective. First, by doing more with less, those who take charge directly contribute service resources to their bosses, such as saving time with more succinct procedures. Second, the methods, procedures, and policies improved by those who take charge may benefit the whole work unit for which the leader is responsible. Third, with an improvement-oriented mindset, followers who take charge help their leaders better achieve organisational goals and visions.

To examine the potential effect of a follower taking charge, we surveyed 230 leader-follower dyads in two five-star hotels in China. Leaders were asked to rate an average of four followers who were randomly chosen by us. They rated their followers’ proactive behaviours at Time-1 and their contributed service resources two months later (Time-2). Another four months later (Time-3), followers reported the relationship quality with their leaders. The results showed that followers who take charge were perceived by their leaders as contributing more valuable service resources and subsequently had better relationship quality with their leaders.

A natural follow-up question is “Do all leaders view the taking-charge behaviour of followers in the same way? What kind of leader is more likely to regard a proactive follower as contributing valuable resources? It’s important to know the answers to these questions, because if leaders do not perceive those who take charge as providing a valuable service, they are not motivated to build good relationship with their group of followers. We sought to answer these questions by investigating leaders’ goal striving. ‘Achievement goal-striving’ leaders aim to complete tasks beyond normal standards and thus are more likely to evaluate followers taking charge as providing a valuable service. Meanwhile, ‘communion goal-striving’ leaders care more about interpersonal closeness and harmony and consequently tend to see followers taking charge as a source of conflict rather than resources. We therefore contend that ‘high-achievement goal-striving’ leaders are more likely — whereas ‘high-communion goal-striving’ leaders are less likely — to develop better relationships with their proactive followers.

The results from our study suggest that leaders with high-achievement goal striving did view their follower’s taking charge behaviour as contributing more valuable service resources and subsequently building better relationships with them. However, our research did not find any significant difference between high- and low-communion goal-striving leaders. This implied that even communion-oriented leaders did not devalue the service value of taking charge followers.

As Milton Berle, famous comedian of the 2oth century, once said, “If opportunity doesn’t knock, build a door.” Our findings indicate that the first move followers can take to build better relationships with their bosses is to seize any opportunities to take charge at work and demonstrate their service value, especially when working with leaders who strive for achievement. In order to stimulate the development of high-quality leader-follower relationships, we encourage organisations to offer leadership development programs that equip leaders with sufficient knowledge and ability to appreciate followers who take charge. We also recommend that leaders periodically re-assess their relationship quality with each of their direct reports to ensure that everyone has a chance to be considered as in-group members given their proactive contributions to the work unit.

♣♣♣

Notes:

- This blog post is based on the authors’ paper Reversing the lens: How followers influence leader–member exchange quality, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 92, Issue 3, September 2019.

- This blog post gives the views of its author(s), not the position of LSE Business Review or the London School of Economics.

- Featured image by InspiredImages, under a Pixabay licence.

- Before commenting, please read our Comment Policy

Angela Jie Xu is an assistant professor at the School of Business, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China. She received her PhD in organisational behaviour from the University of Macau and MA and BA degrees from Shanghai Jiao Tong University. Her research interest focuses on leadership, proactive work behaviours, well-being, and work-family issues.

Angela Jie Xu is an assistant professor at the School of Business, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China. She received her PhD in organisational behaviour from the University of Macau and MA and BA degrees from Shanghai Jiao Tong University. Her research interest focuses on leadership, proactive work behaviours, well-being, and work-family issues.

Raymond Loi is a professor at the Faculty of Business Administration, University of Macau. He received his PhD in management from the Chinese University of Hong Kong. His research interests include organisational justice, organisational exchanges, leadership, and international human resource management.

Raymond Loi is a professor at the Faculty of Business Administration, University of Macau. He received his PhD in management from the Chinese University of Hong Kong. His research interests include organisational justice, organisational exchanges, leadership, and international human resource management.

Zhenyao (Frank) Cai is a lecturer at SILC Business School, Shanghai University. He is also a lecturer at UTS Business School, University of Technology Sydney. He received his PhD in management from Hong Kong Baptist University. His research interest focuses on leadership, entrepreneurship, business ethics, and mentoring.

Zhenyao (Frank) Cai is a lecturer at SILC Business School, Shanghai University. He is also a lecturer at UTS Business School, University of Technology Sydney. He received his PhD in management from Hong Kong Baptist University. His research interest focuses on leadership, entrepreneurship, business ethics, and mentoring.

Robert C. Liden is a professor at the College of Business Administration, University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). He received his PhD in organisational behaviour from the University of Cincinnati. His research interest includes leadership, interpersonal processes, trust, groups, cross-cultural influences, careers, social networks, ethics, and personality.

Robert C. Liden is a professor at the College of Business Administration, University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). He received his PhD in organisational behaviour from the University of Cincinnati. His research interest includes leadership, interpersonal processes, trust, groups, cross-cultural influences, careers, social networks, ethics, and personality.

Thank you for your sharing. It’s great reference for my teaching.